Cycling in Cambodia: what a bike trip to Phnom Penh’s newest tourist attraction reveals about how lives in the capital are changing

- The new US$12 million Win-Win Memorial in the capital’s north provides an enticing destination for one Phnom Penh resident fresh off self-imposed isolation

- Relentless development means modest village areas where children still play by river banks may not survive much longer

A bicycle ride in Cambodia is guaranteed to offer the following: waving children shouting hello, boys on bikes too big for them trying to race you, dusty tracks past dusty fields, and someone selling cold Coca Cola and Carabao from a large red cooler.

On a recent ride, however, anti-Covid-19 scarecrows – a traditional rural response to sickness, using old clothing stuffed with straw to resemble people (some even with plastic guns for extra menace) – hung outside houses to ward off the virus. The lack of face masks and social distancing, however, suggests the people in Cambodia do not feel too threatened.

Earlier this month, as my self-imposed isolation was coming to an end, I yearned to escape the four walls of my flat and once again see life outside Phnom Penh. A cycle ride from the heart of the capital, an ever-growing city of 2 million people, through its rural suburbs and eventually leaving the city behind would be the perfect opportunity to once again stretch my legs, get my too-clean bike dusty and explore the different sides of Cambodian life.

I decided to mark my first adventure out of the city in two months by cycling 20km (12 miles) to see the latest addition to Phnom Penh’s list of tourist attractions: the US$12 million Win-Win Memorial commemorating the actions (and myths) of Prime Minister Hun Sen – the man who finally brought an end to the murderous Khmer Rouge guerillas.

My journey to the memorial – located in the north of the city in what was formally dusty scrubland – starts from the grand Independence Monument in the city’s centre, which celebrates the end of Cambodia’s period of French colonial control in 1953. On the wide tree-lined boulevard, this area is home to some of the city’s greenest spaces (notably a low bar in Phnom Penh) and is also a snapshot of the internal and external powers that have shaped the country.

There is a memorial to the late King Norodom Sihanouk, who had close ties to Beijing; the city home of the prime minister, and the neighbouring North Korean Embassy; and the giant Naga World casino complex, which has thankfully turned off its luminous LED light display while casinos remain closed due to Covid-19.

Just to the north is the large statue commemorating Vietnam’s role in pushing out the Khmer Rouge, a bold statement in a country that continues to struggle with how to treat its long-marginalised ethnic Vietnamese residents, which number some 200,000.

The road that runs north to the Royal Palace remains blissfully closed to cars, and on any given evening is home to families sitting outside snacking, housewives doing group aerobics, children playing and teenagers taking selfies – scenes which are again coming back as virus fears lessen.

So the French restored Angkor Wat’s glory? Historian calls them out

How new buildings complement, compete with and ultimately replace the old is a perpetual, universal struggle in Cambodia. This is starkly highlighted after I cross the Cambodian-Japanese Friendship Bridge (the tallest “hill” in the area and a favourite for cyclists training for races) and continue my leisurely ride north, hugging the riverbank on bumpy narrow roads that alternate between concrete and gravel.

Here once stood a modest Catholic church, built in 1919 by Carmelite nuns and one of the only Christian buildings to survive the targeted Khmer Rouge destruction of all things foreign. It was recently reduced to rubble.

As I passing napping animals and their owners, it seems clear that their modest homes and rural lives will not last much longer … What they are building today will not likely be for them tomorrow

Development is happening on a larger scale further inland, as former scrubland and fields are drowned in river sand to make way for gated communities, new university compounds, wedding halls, and the restaurants, malls and car dealerships needed to sustain the growing aspirational middle classes.

Passing through the modest villages that line the river banks, where children play in front of wooden single-storey homes shaded by fruit trees, and where the village Buddhist temples were once the largest structures, it is unclear how much longer these communities can hold on.

When I moved to Cambodia five years ago, this area did not feel like an extension of Phnom Penh. Instead it was decidedly rural, with rice fields, narrow tracks, and little taller on the horizon than palm trees.

When construction of the new national stadium was announced, its location so far from the city was met with puzzlement. However, the relentless growth of the city outwards in the subsequent years means that when Cambodia hosts the 2023 Southeast Asian Games, at least some of the spectators will not have to travel far.

Cows, goats and chickens share the trail with me as I meander slowly past mango plantations and vegetable plots on my way to the memorial, a grey needle gradually growing on the horizon.

The memorial itself is monumental in design. Tons of polished granite and marble cover every surface, and the vast car park optimistically appears ready to accept half of the city. Whether due to lingering post-coronavirus caution, the 40-degree-Celsius (104-degree-Fahrenheit) heat, or a lack of local interest, I was one of only a handful of visitors that day trying to decipher the murals and the stories they are attempting to tell.

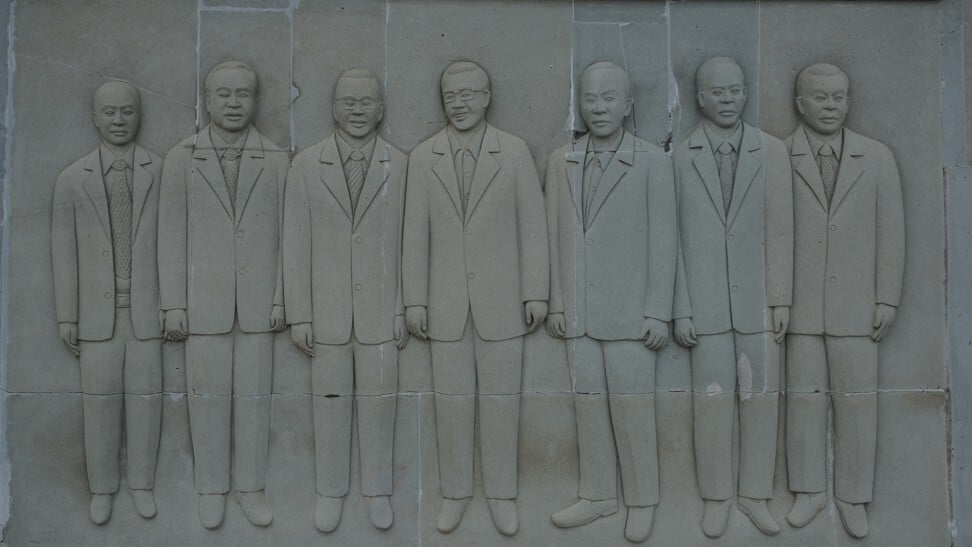

The marble pillar, sitting on top of a marble base housing documents relating to the surrender, is wrapped in a series of carved murals depicting various scenes of Hun Sen’s life. These span his time as a Khmer Rouge soldier; his return from Vietnam, where he had been exiled following internal purges, to push the Khmer Rouge from power; his encouragement of Khmer Rouge soldiers to defect to the government; the Win-Win policy, which guaranteed peace and security for all, whatever their political leanings; and his role at, or near, the top of Cambodian politics ever since.

It is a fascinating window into the country’s recent history, and how Hun Sen and his Cambodian People’s Party wish to portray their central role and message: that everyone has benefited from the ending of the conflict with the Khmer Rouge and the subsequent peace and prosperity.

As a monument to Hun Sen’s legacy, the structure is unlikely to make its mark on global architecture and history like the temples of Angkor have. Yet as a cycling escape from Phnom Penh, it offers a fascinating glimpse at how one of the world’s longest-serving leaders wishes to be remembered, as well as a first-hand glimpse into how life for some Cambodians has changed since 1998.

Is Hun Sen losing his decades-long grip on Cambodia’s corrupt politics?

The 11am heat is oppressive at the largely unshaded memorial, and all that granite and marble isn’t helping. Returning back to the city presents Phnom Penh’s ever-changing skyline in full view. With new flats and office towers in the capital seemingly sprouting every day, this view of the city is always a reminder of how the vertical construction is not representative of the wider country.

As I passing napping animals and their owners, it seems clear that their modest homes and rural lives will not last much longer. With many providing the labour for the construction taking place nearby, they will be called to leave for new projects upon completion. What they are building today will not likely be for them tomorrow.