Marco Polo’s book on China omits tea, chopsticks, bound feet – even the Great Wall. Why does his myth endure, 25 years after author sowed doubt the ‘great explorer’ travelled east – or ever existed?

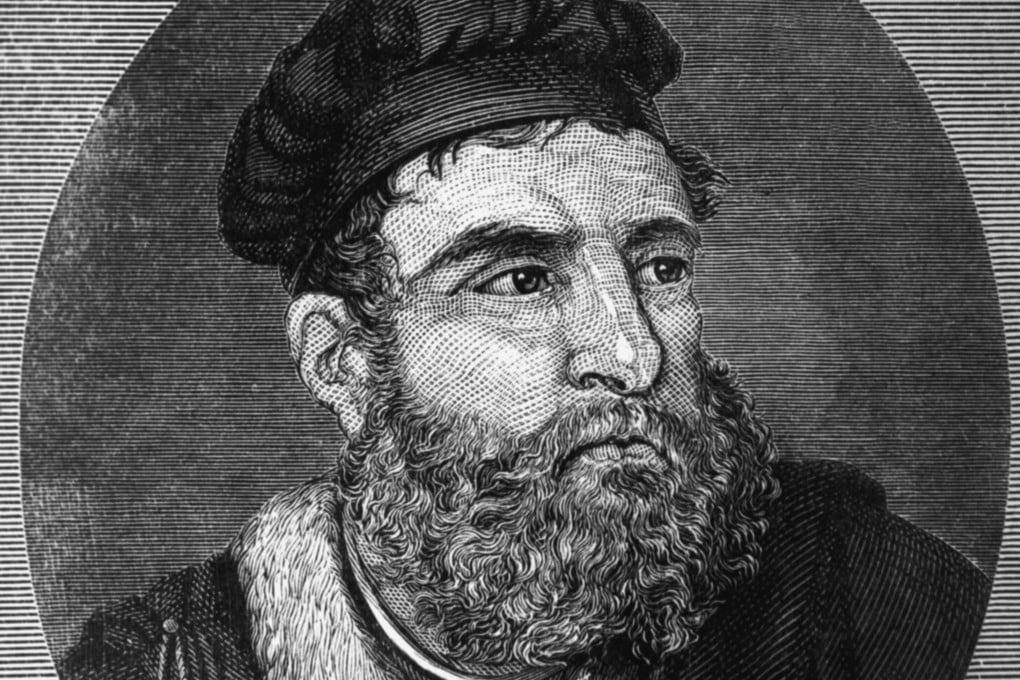

- Marco Polo, a Venetian adventurer, is famous for travelling to and around China in the 13th century and co-writing a book on his journey while imprisoned

- Despite evidence to the contrary, Polo and the experiences he recounts are considered historical facts

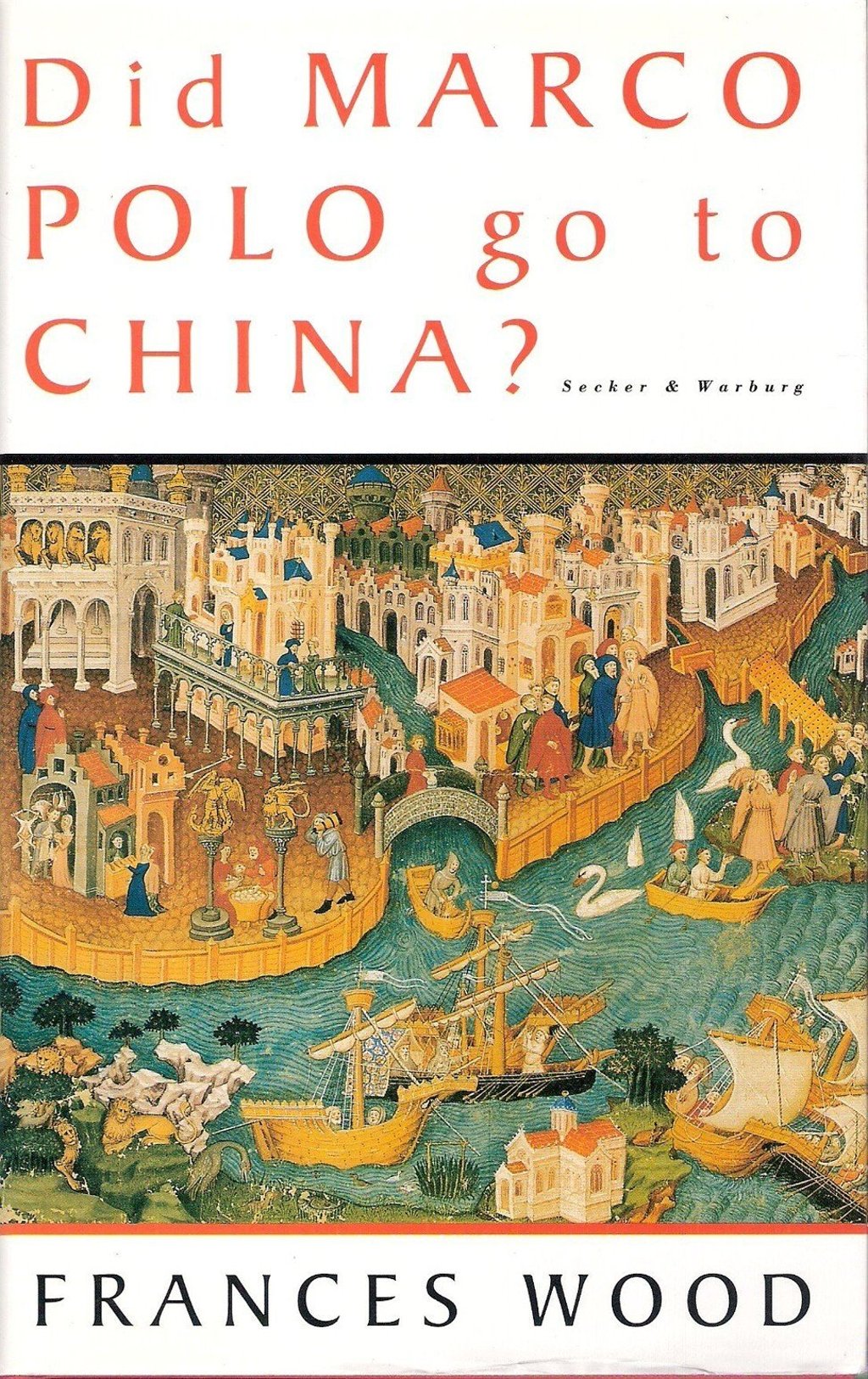

Twenty-five years ago Dr Frances Wood, curator of Chinese collections at the British Library, wrote a book whose title posed a question: Did Marco Polo go to China? Her conclusion was “probably not”.

She was fairly sure the 13th-century Venetian lad of popular imagination who walked to China with his father and uncle, and who sailed home again 24 years later, never existed at all.

The response she received took her aback. “There was an absolute furore about it,” she says. “I went to work as usual to discover there was a Times leader about it and that television companies had been ringing the British Library all through the night.”

Her arguments were familiar to Mongolists studying China’s Yuan dynasty, yet little discussed among sinologists, and completely unknown to the general public, who reacted as if they’d just been told that the Earth was flat.

The book’s arguments were not hard to understand, and often concerned simple inconsistencies, inaccuracies and omissions in Marco Polo’s The Description of the World, commonly known as The Travels. This was supposedly written down by famous romance writer Rustichello at Polo’s dictation in 1298.

The evidence against Polo was publicised in interviews, articles and reviews, and set out again in a subsequent television documentary. Yet just four years after the book’s publication, business information service Bloomberg named Marco Polo as one of the most influential businessmen of the past millennium.