Is this the end for India’s last Chinese-language newspaper? Editor’s death leaves questions over Seong Pow’s future

- The Overseas Chinese Commerce of India, or Seong Pow, has been published in Kolkata since 1969 and was once in much demand by the city’s Chinese population

- But with the pandemic forcing printing to stop in March, and the elderly editor’s death in July, it is unclear whether another edition will be seen

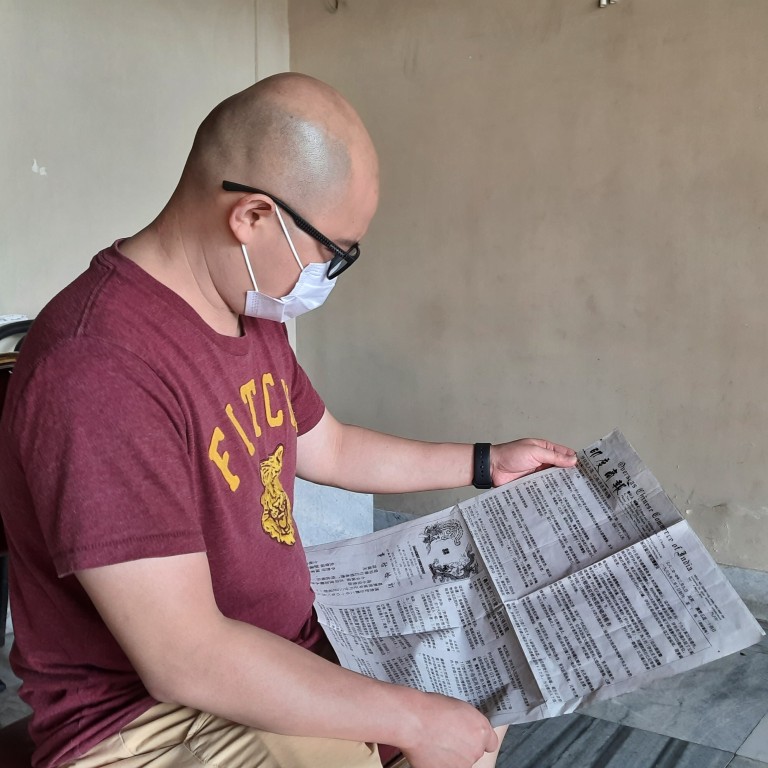

Before India went into coronavirus-enforced lockdown in March, each day would begin early for Kuo-tsai Chang, editor of the country’s last Chinese-language newspaper.

As he had done almost every working day for more than 30 years, the former tanner cycled to his Kolkata office, ensuring he reached his newsroom before 8am. His first task, like many an editor, was to scan through the important news stories of the day. Next, he would busy himself readying the next edition of the Overseas Chinese Commerce of India, or Seong Pow, a more straightforward task in 2020 than it had been in the 1980s.

Back then, the four-page journal was written completely by hand. A team of four or five – including assistants, an accountant and translator – published 2,000 copies daily, to cater to Kolkata’s Chinese population. A Chinese desktop publishing machine did away with the need for handwritten pages in 1989 and, in 1997, the newspaper acquired a printing press.

Until March, the paper was running smoothly, even though its subscriber base was dwindling. However, the pandemic hit and, for the first time, Seong Pow’s press stopped, the elderly editor deeming it unwise to travel into work while the coronavirus was on the loose.

Today, the door to the newspaper’s office – within which are two tables, two computers, two landline phones, two cupboards, a few chairs, a printer and a rack full of brittle old newspapers – is locked shut and the Chinese Tannery Owners’ Association building in which it can be found is deserted.

The dedicated KT Chang, as he was widely known, will never again set foot inside his office because he died in July, his death unconnected with the pandemic, according to his son-in-law, Patrick Lee. A hard-of-hearing septuagenarian who traced his roots to China’s Hakka people, Chang left behind a legacy and a void.

5,000 years of the sari, still at the forefront of fashion

“He always wanted to remain connected with his roots and language. And this is the reason he was involved with this tabloid,” says Lee, a translator by profession. “Therefore, he always ensured this newspaper came out every day, even though only a few readers were left.”

The newspaper’s roots go back to 1969, when Kolkata had a sizeable Chinese population, most of whom were involved in the tannery business. Influential in that industry was Lee Youn-chin, who started the tabloid and allocated space for the newspaper in the Chinese Tannery Owners’ Association building.

“The Overseas Chinese Commerce of India was started by my grandfather,” says Stephen Lee, who runs a restaurant in Kolkata. “Its purpose was to provide news related to tannery or business among our communities.”

Lee Youn-chin’s was not the first Chinese newspaper in India, though. That honour belongs to the Chinese Journal of India, which was first published in Kolkata in 1935. That paper folded in December 2001, brought down by union problems.

When the Seong Pow started it was in much demand, Stephen Lee says. “However, down the years its circulation thinned, just like the Chinese community in Kolkata.”

Before the pandemic, the office opened for only four hours, from 8am to noon, Monday to Saturday. The bespectacled Chang, the paper’s fifth editor, preferred primitive methods. He would cut and paste on translucent paper sheets using a ruler, paper cutter and cellophane tape. His assistant, Helen M Young, helped him search for news on Chinese websites. Together, they would select news items and translate them, design the four-page tabloid and proofread it.

Only 200 copies were being printed daily before lockdown, each selling for a meagre 2.50 rupees (3 US cents).

“India has not much scope for Mandarin speakers and students prefer to learn English over Mandarin,” says Jeff Lee, who is Stephen’s cousin and also runs a restaurant. “Till our father’s generation, [Chinese] people would go to the Mandarin school. The current generation doesn’t know Mandarin. In fact, we know Hindi or Bengali better than Mandarin.

“As our family started this newspaper, we still subscribe to it and we will do so forever. But let me be honest, we can’t read or write Mandarin Chinese,” he adds. “But my mother still looks forward to reading this paper.”

The history of Chinese settlers in India goes back to the British colonial era when, conventional wisdom has it, a sailor named Yang Dazhao (also known as Tong Achew, or Achhi), was caught in a storm in the Bay of Bengal. He and his crew took refuge in Kolkata (then Calcutta) harbour. Achhi received a favour from the then governor general of British India, Warren Hastings, in the shape of land (Kolkata’s Achipur area) on which to develop a sugar plantation, sugar mill and piggery. He was also permitted to bring indentured labour from China to India.

According to the Indian census, the city was once home to around 30,000 Chinese migrants. Two Chinatowns (Tangra and Tiretta Bazaar), several Chinese temples along Tangra Road and a Chinese-language school are testament to a once-flourishing community in Kolkata. Chinese faces are rare in the Chinatowns now, though, and the school, named Pei Mei, is currently shut, because it doesn’t have enough students and has been struck by internal politics.

As a community, the Chinese of Kolkata suffered a body blow in 2002, when India’s Supreme Court ordered that the 230 tanneries in Tangra be relocated, to help reduce pollution in the city. Bantala, 25km (16 miles) from the city centre, was proposed as an alternative site, but it remains largely unoccupied, and most of the former tannery workers have changed profession – many becoming restaurateurs – or moved away.

My parents would wait for the paper. The best part, they recall, were the announcements about their community

The entrance gate to the Chinese Tannery Owners’ Association building is dominant and bears a white sign bearing black Chinese characters. Inside the building are three rooms, one of them Chang’s inner sanctum.

“The office was the small world of Chang. Always engrossed in his work, he rarely spoke to visitors,” Patrick Lee recalls. “But when it came to the newspaper, he would be very enthusiastic.”

The front page would carry international news; page two was a mix of China-specific news and that about Kolkata’s Chinese diaspora; page three contributed pieces on health care and stories for children; while page four bore news from Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan.

The tabloid had a few advertisements, its only source of income. It also published birth, marriage and death announcements, and listed social events.

“My parents would wait for the paper,” says another Chinese restaurant owner, who has requested anonymity. “The best part, they recall, were the announcements about their community.”

“The paper serves as my only link with my Chinese past,” said reader Clarence Tan, in a 1993 interview with the India Today news magazine.

Distributed mainly within its home city, a few copies of the Seong Pow were mailed to Delhi and Mumbai, to readers who had moved from Kolkata. Until 2020, a special edition for Chinese New Year had been published without fail.

Kolkata now has around 2,000 Chinese residents. With the paper’s editor dead, it is unclear when – or even if – they will see another edition of the Seong Pow.