COP26: how the climate crisis could affect tourism, and the Asian destinations most at risk from extreme weather events

- Whether or not cross-border travel is taxed or limited to combat carbon emissions, the tourism industry will have to adapt to the impacts of climate change

- Few parts of the world are in more danger than Asia, home to some of the nations most exposed to climate risk and most likely to suffer extreme weather events

For the human race, the future is uncertain. The stakes couldn’t be higher than at the global conference that will begin in Glasgow, Scotland, on October 31.

At COP26, the survival of humankind as we know it will be on the line as world leaders wrestle with the necessity to keep the planet as cool as possible. Although the climate crisis is already unfolding and will undoubtedly worsen, many experts believe we have the means – the wealth and know-how – to still avoid its worst ravages. All that’s lacking is the political will.

The return of post-pandemic tourism and its associated carbon emissions, when viewed as a contributing factor to the potential extinction of the human race, may be considered a troubling development, but millions of livelihoods are dependent on the industry and it seems unlikely people will be willing to stop travelling for pleasure just yet.

There’s no higher ground for us … it’s just us, it’s just our islands and the sea

As with much else on the planet, though, the tourism industry will increasingly be affected by the climate crisis, both in terms of how weather patterns change and what regulations, taxes or other restrictions governments place on the movement of people across borders to lower their carbon emissions.

There may be short-term winners from the changes – countries with wealthy populations that increasingly stay at home rather than jetting off for their holidays, for example – but among the many losers, some will suffer severe effects earlier than others.

Residents of low-lying nations such as the Maldives archipelago in the Indian Ocean and of regions prone to ever more intense forest fires will have an increasingly difficult time just staying put, let alone convincing tourists to visit. However, the consequences of climate breakdown for countries that are not so obviously sinking or burning may be a little less obvious to gauge.

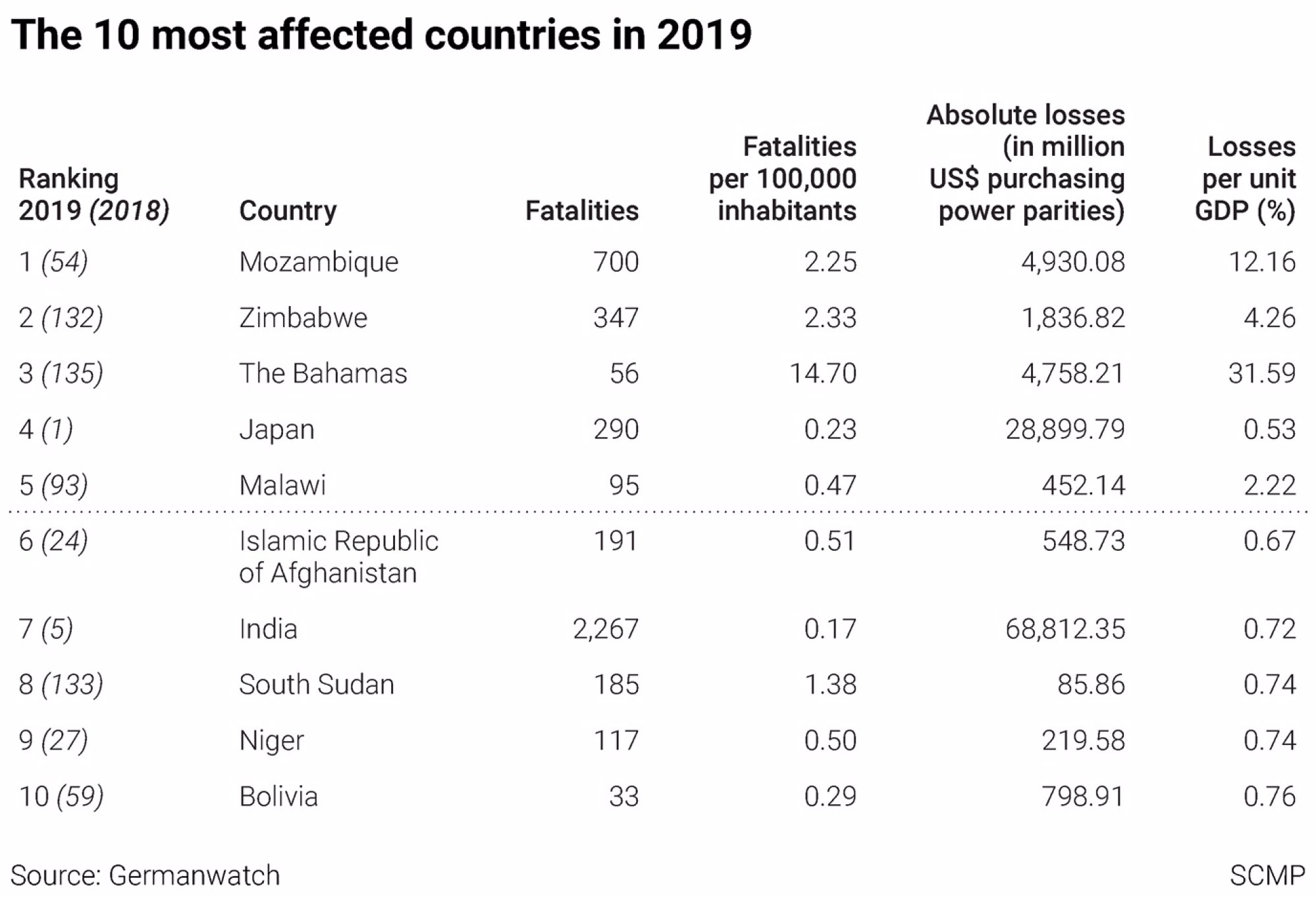

Every year, non-profit NGO Germanwatch publishes the Global Climate Risk Index, which analyses the extent to which countries have been affected by weather-related events, by taking into account lives lost and financial costs incurred.

Although not a comprehensive scoring of climate vulnerability – the analysis focuses on extreme weather events such as storms, floods and heatwaves but does not take into account slow-onset processes such as rising sea levels, glacier melting or ocean warming and acidification – the research does give a sense of which countries are being hit hardest and most directly by the changes in the climate.

“It is important to note that the occurrence of a single extreme event cannot be easily attributed to anthropogenic climate change,” stresses the Bonn, Germany-based NGO. “Nevertheless, climate change is an increasingly important factor for changing the likelihood of the occurrence and the intensity of these events.”

The Global Climate Risk Index 2021, published in January and covering 2019, was accompanied by a second list, concerned with the period 2000-2019. Mozambique and The Bahamas appear in the top 10 of both lists; of the remaining 16 countries, nine are in Asia, including some popular tourism destinations.

Japan and India were among the the 10 nations worst affected by climate events in 2019. When climate events of the past two decades were considered, Myanmar, The Philippines, Thailand and Nepal all placed among the 10 hardest hit countries.

In October 2019, Japan was hit by Typhoon Hagibis, the most powerful storm the country had seen in more than 60 years. With wind speeds reaching 250km/h, Hagibis put paid to two Rugby World Cup matches before delivering up to 1,000mm of rain in 72 hours to the Tokai, Kanto and Tohoku regions (70 per cent of the annual average). Nearly 100 people died and 13,000 houses were destroyed or damaged.

At the time, Japan was still trying to recover from September 2019’s Typhoon Faxai – one of the strongest typhoons to hit Tokyo in a decade and which had left more than 900,000 homes without power. The economic damage caused by the two typhoons is estimated at US$25 billion.

In India, monsoon conditions, which usually last from June to early September, continued for a month longer than usual in 2019, with the extra rain causing floods that took 1,800 lives across 14 states and displaced 1.8 million people. Economic damage was estimated to be US$10 billion.

The year was made more miserable by eight tropical cyclones (six of them “very severe”), representing one of the most active Northern Indian Ocean cyclone seasons on record. The worst, May’s Cyclone Fani, affected 28 million people, killing nearly 90 in India and Bangladesh and causing economic losses of US$8.1 billion, according to Germanwatch.

The list for the period 2000–2019 is based on the average Credit Risk Index values given by the NGO for each of the 20 years covered. “The list of countries featured in the long-term [top] 10 can be divided into two groups,” says Germanwatch. “Firstly, those which were most affected due to exceptional catastrophes and secondly, those which are affected by extreme events on an ongoing basis.”

“Its destructive force – 215km/h winds and a vast tidal surge – swept away low-lying areas on the fingers of land known as the Mouths of the Irrawaddy. Children were pulled from their parents’ grasp as waves swept over villages in the darkness, reaching more than 30km inland. Entire towns were destroyed.”

Countries affected by extreme events on a continuing basis include the Philippines, which is regularly exposed to fierce typhoons due to its geographical location. Typhoons Bopha (2012), Haiyan (2013) and Mangkhut (2018) were among the most destructive during the 20-year period under the microscope.

Countries’ vulnerability to extreme events as highlighted by the indices should be understood “as warnings in order to be prepared for more frequent and/or more severe events”, says Germanwatch. With climate information collected from 2020 – which equaled 2016 as the hottest on record – the NGO’s Global Climate Risk Index 2022 will no doubt make for grim reading.

Reports such as those from Germanwatch show that the effects of climate breakdown do not fall equally. And they suggest that, in the near term at least, countries in Asia are likely to suffer more than most.