How public transport systems built a city: San Francisco marks 150 years of its cable cars and 125 years of Ferry Building, hub of its ferry routes

- The US city’s cable car network is celebrating its 150th anniversary and at its heart is the Cable Car Museum, which reveals the system’s innards

- The Ferry Building, hub of its ferry routes, opened 125 years ago, and is now a popular place in which to hang out, full of bakeries, restaurants and shops

It’s not often that a public transport system is a draw in its own right, but the remnants of two in San Francisco are high up on that city’s list of attractions, both of them celebrating anniversaries this year.

The Union Depot and Ferry House – more commonly known simply as the Ferry Building – has been in operation for 125 years as the hub of a network of ferry routes across San Francisco Bay, and has re-emerged from near-obsolescence to become a hub of activity again.

It’s no longer a place to rush through but one to dally in, although setting off around the bay in a boat remains an option.

Meanwhile, the city’s cable car network, built to connect with the ferry services, celebrates 150 years of operation this year.

Its ancient tram-like cars are drawn up San Francisco’s steep hills by a cat’s cradle of underground hawsers – a technology invented in this Californian city.

The interior of the dignified Beaux-Arts-style Ferry Building, with its landmark clock tower, would be unrecognisable to those for whom it was once just a hub on the daily commute, a link to a cable car to somewhere else.

Until the 1930s, the only practical way to reach San Francisco from neighbouring communities was by water.

Traffic peaked in the 1920s and ’30s, but the opening of the Golden Gate and Bay bridges sent ferry services into a long decline.

By the mid-’50s, the building had been divided into offices. It was then effectively severed from the rest of the city by the construction of the elevated Embarcadero Freeway, from behind which even the building’s 245ft tall (75-metre tall) clock tower could make little impression.

Best places to see the 2024 Great American Eclipse and 2023 ‘ring of fire’

But the earthquake of 1989 damaged the freeway and its resulting demolition was the beginning of rehabilitation for the Ferry Building, which had survived largely unscathed.

Its refurbishment has seen portions of the upper concourse removed to allow light to spill down to what were once luggage depots along the building’s 600ft-long central channel, now home to bakeries, restaurants, shops and artisans offering everything from Arab street food to Argentinian empanadas.

There’s enough history here for a guided tour to be available, taking you up a grand staircase to the original pier entrances, where a vast mosaic of the seal of the state of California is set in the floor.

There’s still a ticket office for the remaining ferry services or at which to book a tour out into the bay, but this is now described as an adventure. The humdrum has become the heroic.

A short walk from the Ferry Building, at the terminus of one of three surviving cable car lines, the cable can be heard rattling in its slot, which emits an oily aroma. Ahead, the road and central track suddenly shoot steeply uphill. Mechanical assistance with the climb on a hot summer’s afternoon is very welcome.

The patent for a grip-and-release system used with a steel cable specially woven for flexibility was granted to Andrew Smith Hallidie in 1871, and after extensive testing, the first public services began running two years later.

The cars are history on wheels, all wooden bench seats, iron brackets and columns like turned table legs, and they seem to have gone through no changes at all in 150 years.

Drivers wear thick gloves to operate great levers resembling those used to change points in a railway signal box, and which control how tightly the perpetually moving underground cable is gripped by metal jaws beneath the car.

At maximum pressure, the 10 tons of car and passengers are effortlessly pulled up even the steepest hill up to a maximum speed of 9.5mph (15km/h), although the average is only 5.5mph.

The cable is lubricated, which allows a gentle start as it partly slithers through the jaws of each car’s grip, acceleration coming as the tightness of the grip is increased. The lubricant is pine tar, which vaporises under pressure to produce a resiny aroma.

Out-of-town visitors, some hanging on to the outside of the car, wave at others taking pictures. The track levels out at the cross streets, where passengers alight, the conductor watching for traffic and calling warnings as necessary.

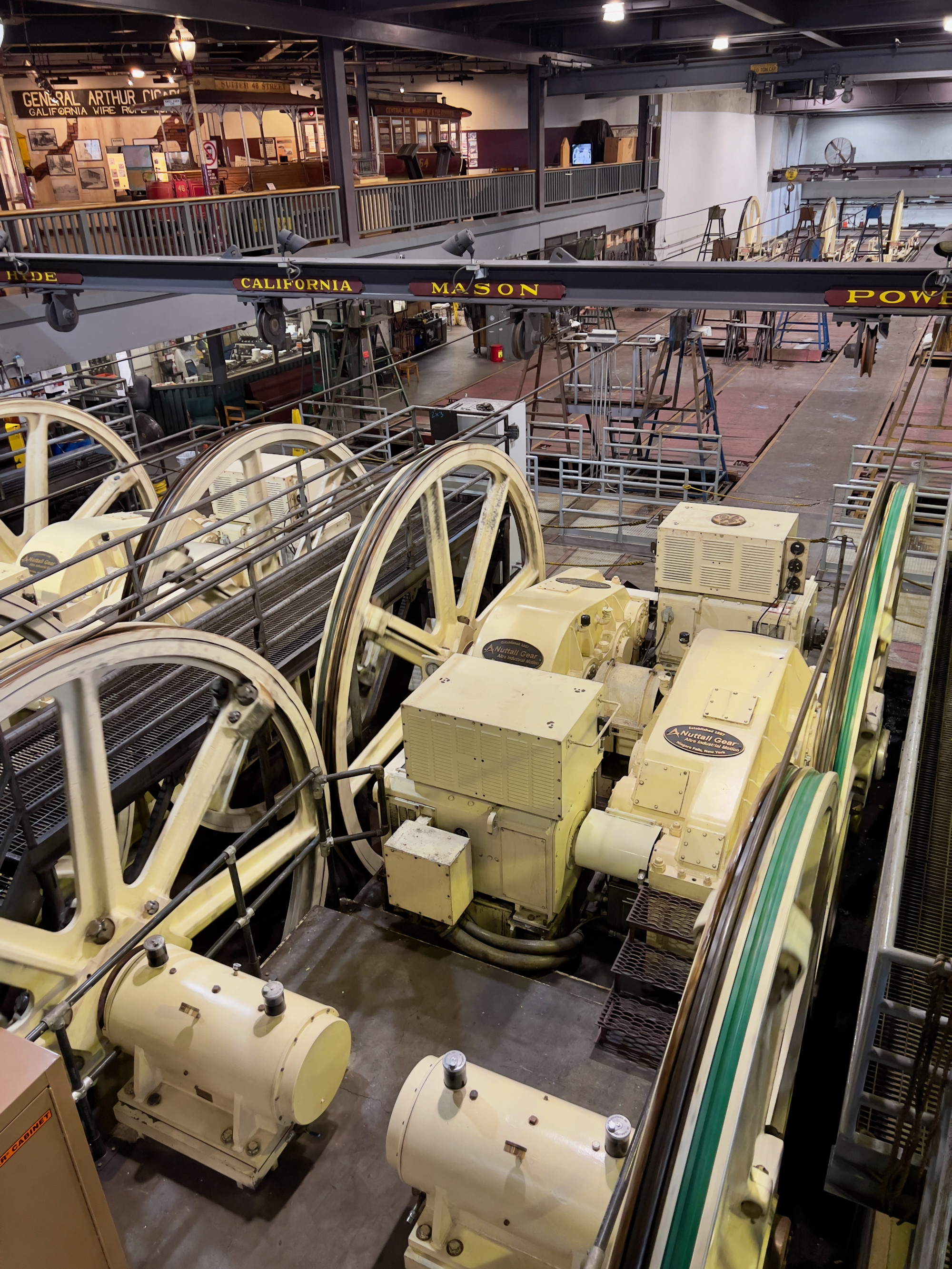

The heart of the system is the Cable Car Museum, from which the three surviving lines still receive their power.

Here, amid displays of equipment, explanations of the technology and historical photographs, the system’s innards are revealed – sets of vast wheels labelled for the lines they run, which spin 19 hours a day, powering and directing the cables, and keeping them taut.

In the heyday of cable cars, nine companies operated 22 lines, all using different gauges. The surviving services were only finally made uniform in 1956. Eight years later, the system was designated a National Historic Landmark – the only one that’s not static.

Visitors are likely to be riding it for another 150 years.