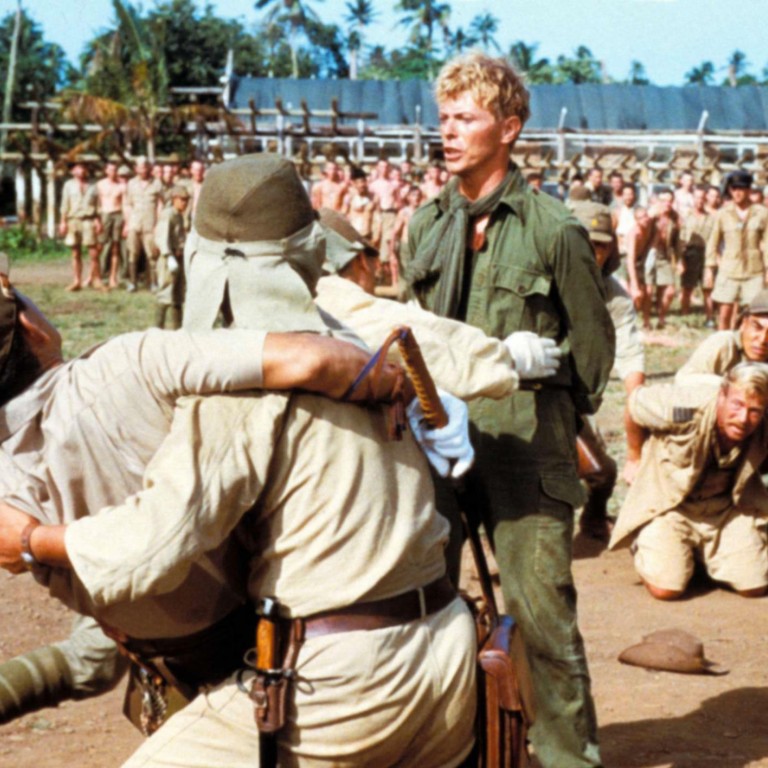

Art House: Merry Christmas, Mr Lawrence shows the brutality of Japanese POW camps

Sean Tierney

There wasn't much to be merry about in a Japanese prisoner of war (POW) camp in 1942, during the Christmas season or any other time.

Allied prisoners were considered worthless by their captors, who saw surrender as a fate literally worse than death. This was, at least partially, the Japanese rationale for their brutal treatment of prisoners.

The threat of such violence is a constant presence in , and is presented in a matter-of-fact way that allows the viewer to understand the reality of the POW environment: hours or days of tedium broken by flashes of violence and death.

But within this cocoon of misery, distractions provided by mischief, perseverance, and thoughts of love helped give both captives and captors the means to carry on with their lives.

In a POW camp on Java in 1942, a new prisoner arrives. Major Celliers (David Bowie) finds himself in the centre of a conflict between Allied prisoners and their Japanese captors.

The camp's young commandant, Captain Yonoi (Ryuichi Sakamoto, who also wrote the film's score), is locked in a struggle with the prisoners' commander, Group Captain Hicksley (Jack Thompson), over the proper conduct and obligations of prisoners of war.

Attempting to mediate this conflict is Lieutenant Colonel Lawrence (Tom Conti), who spent time in Japan before the war and is bilingual. Lawrence spends much of his time with Sergeant Hara (Takeshi Kitano in his first significant dramatic role), whose personality is the opposite of the reserved Captain Yonoi.

Yonoi is fascinated by Celliers, to an extent that is made plain implicitly rather than explicitly. It provides both the central tension of the film's story as well as a perspective through which the film shows us an alternative vision of a seemingly well-worn genre.

There also is a delicate balance at work in between the documentary and the fantastic; the 1983 Japanese-British co-production's highly thematic narrative is played out within — and nearly in opposition to — its realistic setting and historical background.

In addition, director Nagisa Oshima and cinematographer Toichiro Narushima create a world that is richly coloured but also unflinching — there is recognisable beauty, but it is often a backdrop for people and behaviour that are remarkably ugly.

The film's 1980s vintage shows in certain visual and musical ways. Captain Yonoi's face is made up in a style representative of the decade. But the flaws are minor. is a thoughtful meditation on the differences between people, and how they cope with each other.