The Way We Were

Explore the Hong Kong that was through a new film retrospective

It doesn’t get more real in Hong Kong than the movies. Certain movies, anyway. Not the dozen or so triad galmorizations every year, or the equally heavyhanded “historical” epics these days, fun as those can be. We’re talking about the genuine slice-of-life films – the realist films – found across the last half-century of local cinema. Films about the everyday trials and triumphs of both the marginalized and the masses. About men who sleep in cages, schoolgirls forced to work the streets, policemen struggling with temptation. About ordinary people like you, us, Little Cheung, and the folks just trying to get by in Tin Shui Wai. The Hong Kong Film Archive’s current “Care for the Community” program showcases a stellar selection of such films, films which it believes may not just tell us about changes to society across the decades, but hold the key to the ever-elusive question that’s dogged us as a city for the last ten years – who we are.

The earliest of the program’s films is “The Kid” (1950), starring a ten-year-old Bruce Lee. Lee plays an orphan in the slums who sells comics, while his real-life father Lee Hoi-chuen plays a factory owner who pays for his schooling and gives him work. A seminal social realist film for post-war Cantonese cinema, “The Kid” has aggressive political overtones. It depicts the poor as virtuous, compassionate and mindful of family values, while the rich are corrupt, decadent adulterers. The film was based on a socially conscious comic strip by Yuen Po-wan, who plays the factory owner’s spoiled son, a selfish usurper embodying everything that’s wrong with the wealthy. In contrast, director Fung Fung appears as “Flash Knife Lee,” a poor but charismatic petty thief who the titular protagonist looks up to.

The idealization of the grassroots has become a staple of Chinese realist cinema up to the present day. “The Kid” ties to it a fiercely proactive message: that the poor need to unite against the rich, and that if they do so justice will prevail.

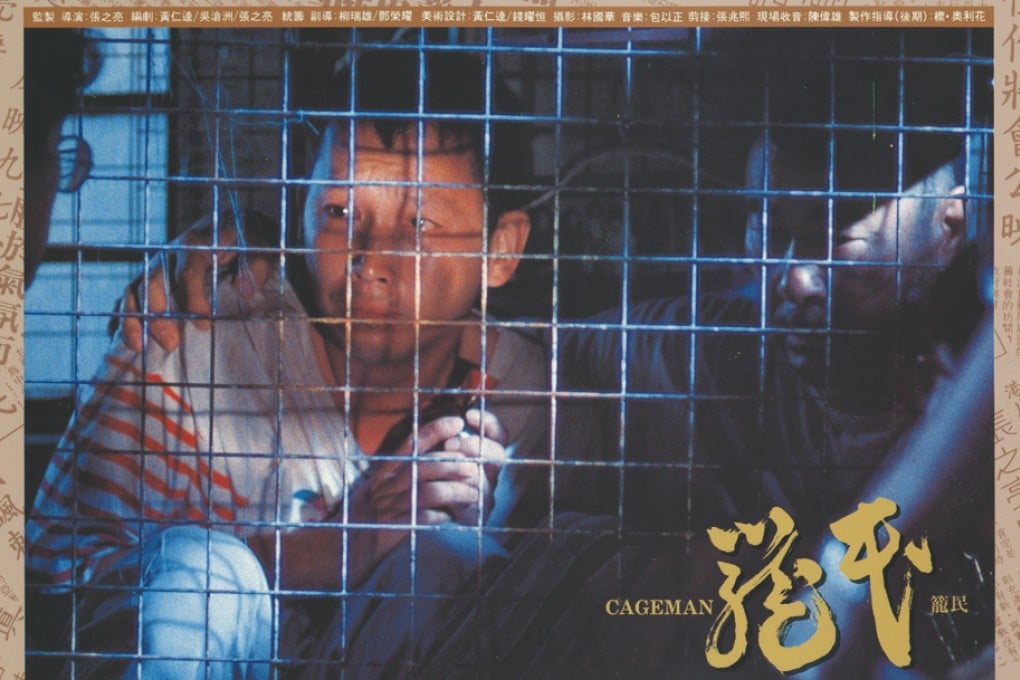

We find a much less certain take of the matter forty years down the line in Jacob Cheung’s cult classic “Cageman” (1992). Starring among others Beyond’s Wong Ka-kui a year before his death, it highlights the very real plight of the downtrodden at the time. Trapped in an overcrowded society with artificially high rent rates, they dwell in wire cages stacked one on top of the other in tenement buildings. The film sees them band together to prevent wealthy developers from demolishing the building and replacing it with luxury condos. Unlike the united poor in “The Kid” and early housing shortage films such as “Save Your Water Supply” (1954) and “Mud Child” (1976), the heroes here are viewed with considerable ambiguity. Motivated by pride and dignity, at the end of the day they are nonetheless fighting to stay in their prison-like conditions rather than transcend them.

Aside from the poor in general, the marginalized individuals featured most prominently in the Cantonese realist spotlight include those trapped in a life of crime. Prostitutes in particular have been portrayed with ample sympathy. Lawrence Lau’s “Queen of Temple Street” (1990) received a Category III rating for the same reason as “Cageman” – foul language taken straight from the streets. The film simultaneously depicts the tragedy of its subjects’ circumstances as well as their grit and integrity. It also revolves around family, and how the latter survives in the toughest of circumstances. Sylvia Chang plays the titular character, an experienced mama san who regrets how her work took over her family life, while Rain Lau debuts as her daughter, a high-school dropout who turns to prostitution at 15 (she was awarded two Hong Kong Film Awards for her performance). The cross-generational differences between the two sex workers can also be gleaned from “The Call Girls” (1973), revealing how the sex trade flourished in the 70s with police collusion, and “Lonely Fifteen” (1982), which starred real former runaways who turned to prostitution in their teens.

Youth and emerging identity are naturally persistent themes throughout the history of modern Cantonese cinema. Like “The Kid,” Fruit Chan’s “Little Cheung” (1999) idealizes the innocence of the child, though for largely different reasons. While the earlier film celebrates the child’s freedom from the decadence and corruption brought by wealth, Chan’s third “handover trilogy” film cherishes the child’s freedom from political prejudice and ideology. The title character is a nine-year-old boy who helps his father with deliveries from a small restaurant on Mongkok’s Portland Street. Little Cheung brings food to triads, prostitutes, coffin-makers, and mean cops. He also befriends a girl his age from the mainland, smuggled over illegally with her mother. While adults from either side of the border remain wary of one another as the handover looms closer, the relationship between the two children is unshaken.