Sea Sick

The harborfront is not the only part of our marine environment that’s endangered. Sarah Fitzpatrick explains what can be done to prevent rampant overfishing.

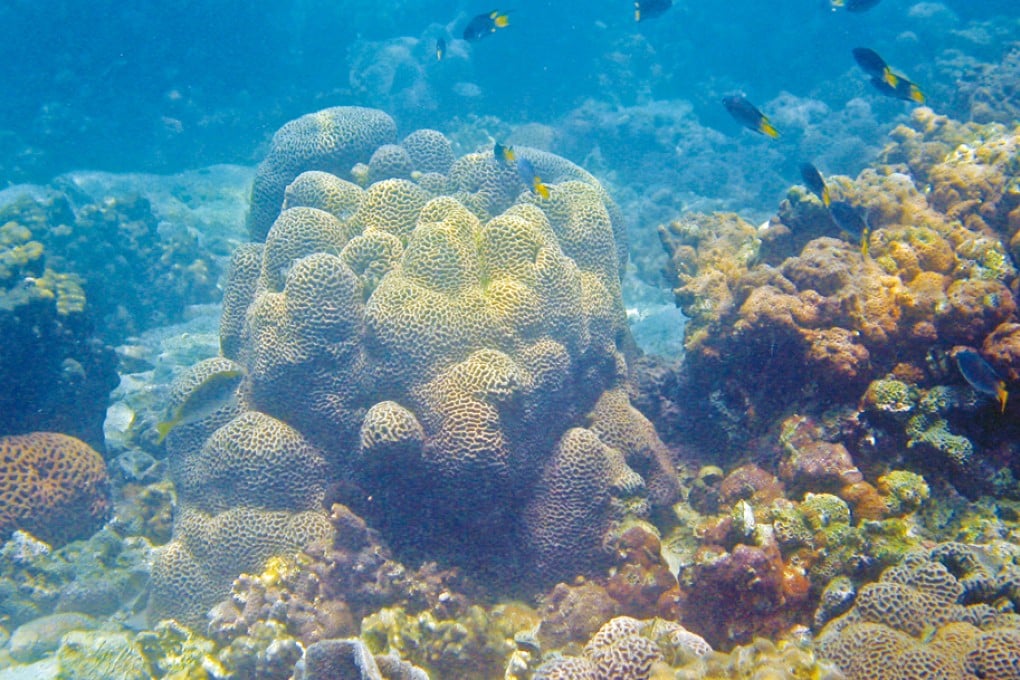

In April this year, an 85kg Chinese Bahaba fish was caught off Lantau. Sounds impressive, but when you consider that the current average weight of the local fish catch from trawling in Hong Kong weighs a mere 10g, you realize how rare this find really is. Irresponsible fishing is drastically depleting our waters. And this is a terrible shame because believe it or not we are home to over 80 hard coral species (more than what’s found in the Caribbean), and the seas around Hong Kong contain 1,000 fish species, including sharks, manta rays, white dolphins, sea urchins and green turtles—it’s just that we barely see them. According to a report released by the World Wildlife Foundation (WWF), the biomass of large fish (an important indicator of the health of an ecosystem) associated with the Hong Kong seabed has dropped by more than 80 percent in the past 50 years.

Join the Campaign

On June 8, the WWF’s “Save Our Seas” campaign will end. The campaign aims to collect signatures from the public to encourage the government to implement long-term marine conservation measures (see box, right). The initiative aims to tackle marine wildlife depletion on a number of fronts: to ban fishing in existing marine parks, to designate 10 percent of Hong Kong waters as “no take zones” to encourage fish population growth and to implement a mandatory licensing scheme for commercial fishing boats on top of enforcing catch quotas. Clarus Chu, the Senior Marine Conservation Officer at the WWF, explains that the greatest threat to Hong Kong’s marine ecosystem is the lack of government oversight. “Anyone who owns a boat can catch as many fish as they want. Currently, there are no quotas and no licensing systems. The government does not keep a detailed record of what is caught in Hong Kong waters and fishermen are not required to submit a record of their catch.” The current policy is completely at odds with other countries with large coastal areas, including mainland China.

Damage Done

According to a report from the University of British Columbia, commissioned by the WWF, Hong Kong is one of the most intensively fished areas in the world. We are particularly notorious in our use of bottom trawling, in which one or many heavily weighted nets are dragged over the seabed, destroying its ability to support fish populations. Reclamation projects, as well as sewage output into the sea, have impeded the growth of coral and other marine life.

There are currently four marine parks in Hong Kong: Hoi Ha Wan, Tung Ping Chau, Yan Chau Tong, Sha Chau and Lung Kwu Chau, and one marine reserve at Cape D’Aguilar. WWF claims that marine reserves can act as an insurance policy against the collapse of fishing areas, as well as helping to conserve biodiversity. Recent experiments with “no take zones” in the Great Barrier Reef in Australia and Goat Island in New Zealand suggest that they result in a significantly larger and more diverse marine life population, both inside and outside the zone, and that the average fish catch around the perimeter of a no-take zone increases significantly. This is better for local fisherman, explains Chu, as “they can catch more fish and bigger fish than they ever could before.” Conservationist David Woodrige agrees. “Right now the fish catch is very low. By designating areas as ‘no take’ zones, there will be minimal loss to the fishermen, and within a few years there will be a huge gain.” However, commercial fishing is permitted in Marine Parks by license holders. According to the WWF’s monitoring, there is currently no difference between the fish populations inside the marine parks and outside them. Chu states: ”Despite 10 years of protection, we can’t see the effect of the marine parks because fishermen are still able to fish within these supposedly protected areas.” Local ocean conservationist Douglas Woodring agrees, stating that “granting fishermen license to fish in marine reserves is like sending hunters into a zoo.”

Preserve the Reserves

The AFCD, which manages the marine parks and reserve, has declined to comment on the effectiveness of the marine parks to preserve our biodiversity. However, David O’Dwyer, chairman of green group Living Seas Hong Kong, has examined the AFCD’s studies of fish populations inside the marine parks and concludes that “the methods and consequent validity of the AFCD’s studies, from a scientific point of view, is questionable.” Further, O’Dwyer emphasizes that even the AFCD’s own research suggests that fish stocks in Hong Kong have declined. An additional benefit of conserving these protected areas is that it could potentially boost tourism to coastal areas. The study estimates that between $1.3 billion and $2.6 billion could be generated through marine tourism. But is it too late? “We’ve passed a point of no return on a number of species already,” explains O’Dwyer, “but its never too late, there are still pockets of ecology that could recover relatively quickly.” However, it’s clear that any progress depends on the government’s willingness to make marine conservation a priority. “The public overwhelmingly wants a change, and we have the money to do it. All we need is for the government to act, and it needs to act quickly,” says Chu. “The sea belongs to everyone, and we believe that everyone should be able to enjoy Hong Kong’s natural diversity. It’s potentially a win-win situation for everyone, but at this rate it’s lose-lose.”