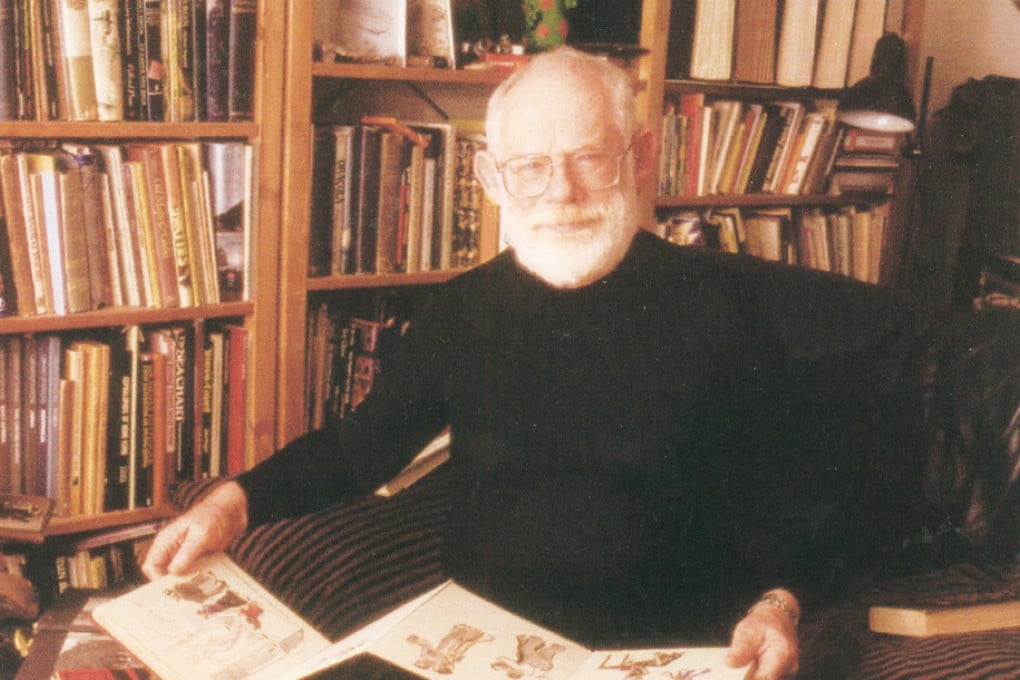

Writer and Artist Arthur Hacker

Among writer and artist Arthur Hacker's many creations is the Lap Sap Chung cartoon spokesman for hygiene and numerous books such as “China Illustrated” and his newest, “Shanghai Century.” Simon Bowring met up with him for breakfast.

HK Magazine: Where are you from?

Arthur Hacker: A difficult question. I’m a British army brat. Though I was born in Salisbury, I moved around quite a bit until the middle of WWII, going between places in Great Britain, Canada, Gibralter and Bermuda. All members of my family live in different countries, and I thus regard “expat” as its own nationality. I’ve lived in Hong Kong for 38 years now, and my Cantonese is about as good as my French. I went to nine different schools, and got kicked out of at least three of them - which was a family tradition, you see. There was no shame in it, and at times I was rather proud of the fact. My mother and aunt had similar records.

HK: How did you start off with design and painting?

AH: I studied at the Royal College of Art in the UK, where officially I did printmaking. I started by designing posters and editorials for the Evening Standard in London, before working at Philips records in London doing cover sleeves. I signed up for a job in the newspaper as the design director for the Government Information Services in Hong Kong in 1967, during the riots, and came later in the year when things had calmed down. It took three days at that time to fly from London to Hong Kong. But my most memorable experience was doing the scenery painting at a strip club in Soho. Because there was a row between the stage manager and the boss, I became the Sunday stage manager for a little while, which was certainly interesting, and paid my rent for the week

HK: What was the GIS like when you first arrived?

AH: When I first got here, there weren’t so many people with artistic skills working under the government umbrella. It was like getting typists to do the work of a journalist. But that’s what made it fun and I actually got a lot of exciting jobs. I did a book in 1976 called “Hacker’s Hong Kong,” a collection of drawings of Hong Kong life. Although I’m convinced it was pop art, everybody else referred to it as a “cartoon.” Hong Kong likes to put everybody in a little box and so I was slid into the cartoonist box. GIS got more bureaucratic as time went on. When I first got here, Hong Kong was a refugee society, which was great in a way because when working with the government, one had the feeling that they were building a society. But it was very laissez-faire and many people saw Hong Kong as a ship sailing under the flag of convenience. Nobody really began talking about politics until the mid-80’s when Thatcher went to Beijing and fell down the great steps of the people.

HK: What do you love and loathe about Hong Kong?

AH: I stayed here because you’re always alive in Hong Kong. It’s the energy, opportunity and lifestyle of the place. You can make a living when you’re 70 here, something which could be very difficult to do in most places. But the greed really gets up my nose. When I first arrived here, I was taken aback as to the ease with which a normal conversation descended into money matters and how much one earned. In the old days, nobody discussed money. It was considered bad manners. [Laughs] That’s probably why the UK’s economy was in a bad place until the days of Thatcher.

HK: Do you ever miss the colonial atmosphere that Hong Kong used to have?

AH: Although Hong Kong had the trappings of a colony, there were few settlers, and you could never really feel the presence of the colonial government, as soldiers stayed almost exclusively in the New Territories and Stanley. There are things in the 90’s about the government that must have sounded terribly colonial, but compared to other places, and compared to conditions only 30 years earlier in other colonies, I don’t think it was too bad. This is because the government here was very independent from the arms of the UK and really came into its own. That said, as the de-colonization of many British colonies in Africa commenced, there were a few bureaucrats from as far away as Swaziland who came to Hong Kong and hated it. I think they were astonished that they really had to work over here.

HK: Do you have any special memories of working at the GIS?

AH: When awareness of the pollution problem first came up, the government was trying to institute the use of rubbish bins in the New Territories. I asked one official where the bins were, as I hadn’t ever seen any, and he told me [puts on exaggerated Victorian accent], “Yes, well we try to keep them inconspicuous, you know.” So I asked him how many bins there were and he replied, “Well, I imagine there are about six.” I later went to investigate and found that these bins were sawn-off oil drums half-filled with water.