Charles LaBelle

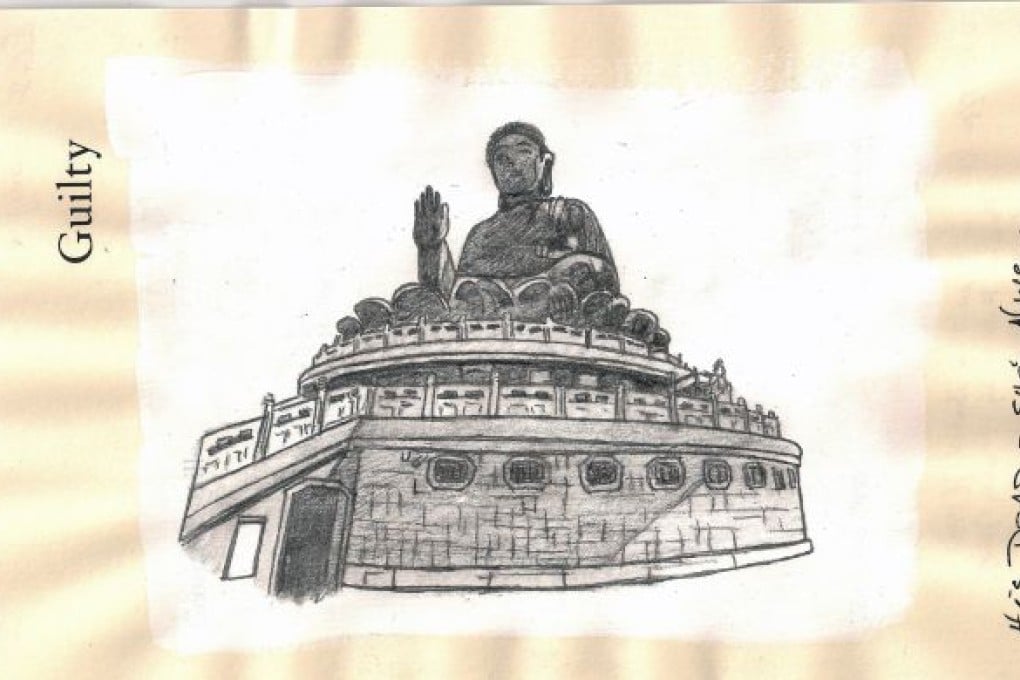

American visual artist Charles LaBelle spent around 14 years making a record of every building he entered, then drawing a selection of them on the pages of books. He talks Leanne Mirandilla about his journey so far.

HK Magazine: How does this project work? What’s the process you go through when you do a drawing?

Chales LaBelle: I just surpassed 14,000 buildings total over 14 years. This year I went to 1,800. When I travel to a new city, I rack up new buildings. The drawings happen after the fact—some a decade later. Most buildings I’ll never draw. When I’m about to enter a new building I take a moment and go across the street, look at the building, make a note of the location and then take a photograph. The project started really just as an exercise in looking—just forcing myself to pause in the midst of busy everyday life and take stock of where I am. I’m here, and the building is there. There’s also a specific engagement between architecture and the body. It’s the moment just prior to entering that I’m documenting. What happens right after that moment is that I get physically swallowed up by the building. I think of it as this very basic attempt to hold on to something. Life just slips through our fingers, or maybe we slip through its fingers. In a way it’s really a sort of intimacy—a search for an intimate moment, like being in the arms of a loved one, a seduction. On a basic historical level, [the project] is just a bunch of buildings that existed at that day and time. Some of these buildings do not exist anymore. I like to fantasize about five years from now, and I think that my project will be more significant for historians rather than art historians. Collectively, what I’m creating is a document of the earth in the first decades of the 21st century.

HK: Is this a project you plan to work on indefinitely?

CL: Yes. 2007 was the 10th anniversary of the project, and at that point I made a decision to stop all other projects. Prior to this, as an artist, I did video, photography, sculpture, installations—always about the city, about this relationship between the city and the body. And [this project] was just this little thing on the backburner. Three or four years ago I just thought, “I can’t do it all anymore. I just want to change my life and simplify things.” So I looked at everything I had been doing and asked, “What’s really important? What has gravitas?” And somehow—my god—this little project, after 10 years, had changed my life. Which is ironic, because when I started the project it was about simply documenting my daily life. After I had done it for a year, I realized that it was changing the way I lived my life. [I’d ask myself,] “Do I want to go into that building? Do I want to have to draw this building?” or “Wow, I really want to go to this building so I can draw it.”

HK: What’s the most interesting building you’ve documented?

CL: I made a whole trip from New York to Italy, to Sicily, to the outskirts of this town, to an overgrown thicket behind a stadium, to find this house where Aleister Crowley lived in the 1920s. Nobody [in the area] wants to talk about it. Crowley was a Satanist, and he moved to this house after being kicked out of England. For five or six years, he and his disciples lived in this house and they practiced Satanic rituals and [did] unspeakable things. They were finally kicked out of Italy. I don’t understand why that house is still there—the house is a wreck. It’s been abandoned since the 20s, it’s totally overgrown, people have broken into it, they’ve graffiti-ed it, they’ve trashed it. Part of it looks like it was set on fire or burned, the government has boarded it all up. As a matter of fact, when I arrived I had to pry off a board from a window to get inside, because for my project it only works if I’ve been inside the building. Besides, I wanted to be inside because there are Satanic murals that Crowley painted himself.

HK: At what point did you move to Hong Kong?

CL: I’ve been living here full-time for two years. I was looking to leave New York because I was very unhappy with New York, and I wanted to go someplace else. After coming to Hong Kong for the first time, I went back home and I thought that Hong Kong was really interesting. I really liked the geography, the architecture, the culture, the history. It’s kind of in between states [of being]—the way that it’s not really China, but it’s no longer Britain.

HK: What usually determines whether you like a city or not?

CL: To be honest, the less familiar I am with a city, the more I like it. One of my greatest pleasures is to just go to new cities. I find this sense of being a stranger and totally lost very comforting.

Browse through hundreds of LaBelle’s drawings at Saamlung Gallery until Jan 7.