Identity Crisis

Compared with Chinese citizens, ethnic minorities face myriad difficulties getting HKSAR passports—even if they were born here. Grace Tsoi investigates the flawed system. Photos by South Ho.

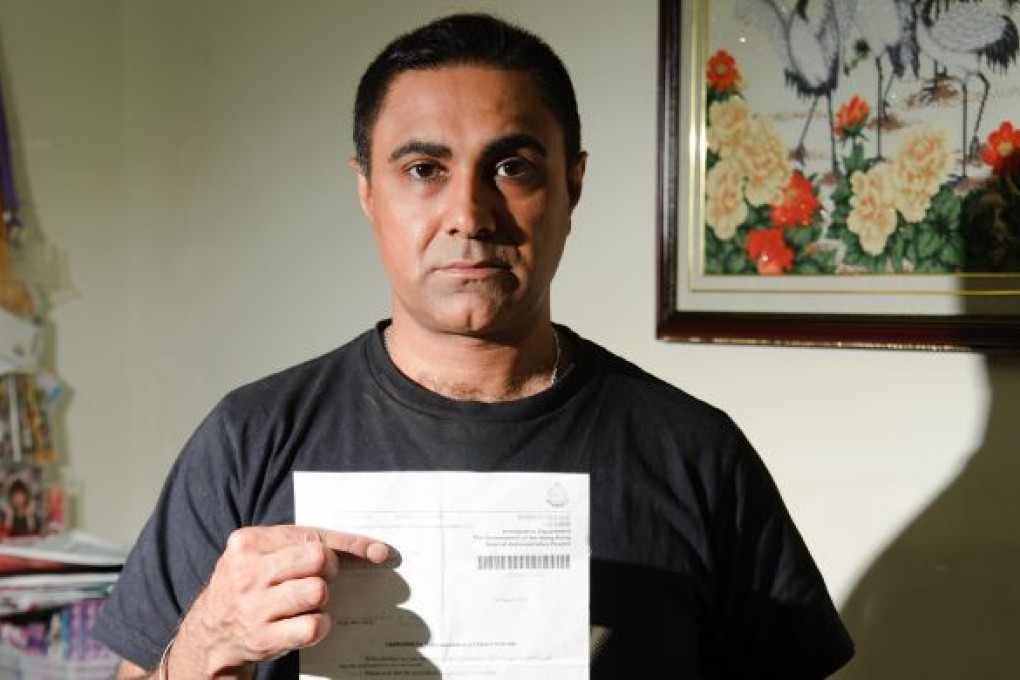

Born and bred in Hong Kong, Gill Mohindepaul Singh—who is better known by his Chinese stage name Kiu Bobo—Is a TVB actor of Indian descent. Though he is extremely popular in Hong Kong households, in part due to his comedic performances and lively character portrayals, the actor may be forced to leave the city if his wife fails to obtain a Hong Kong passport.

Singh’s wife, who is also Indian and not born in Hong Kong, has permanent residency status because she and Singh have been married for more than 20 years. The couple would be content to stay in Hong Kong if it weren’t for their nine-year-old son, who suffers from spinal nerve problems and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Last year, the Singhs decided to move him to Scotland so that he could have better medical care and access to special needs education. The family came up with a plan: Singh would stay in Hong Kong to advance his career and other ventures, while his wife would split her time between Scotland and Hong Kong. But Hong Kong permanent residency does not a passport make: the former serves as local identification and permits its holder to work and reside here, while the latter is a crucial travel document that allows visa-free access to certain countries that other passports do not.

If Singh’s wife held an HKSAR passport, their plan would have worked—no visa is needed for a HKSAR passport holder to go to the United Kingdom. But their plan was shattered by the Hong Kong Immigration Department’s decision to not issue her a passport. An Indian passport holder, she can only apply for a visa to stay in Scotland 180 days a year. But since Singh has a British passport, which he obtained before the handover, he can sponsor his wife to live in the UK. But that means he himself has to stay in the country himself for three years, and can only travel to other countries for 30 days per year.

Singh faces a hard decision. “I was taken by surprise when I found out that my wife’s application was rejected,” he says. “Of course, I don’t want to leave when I am doing so well with my showbiz career.” The restrictions of a sponsor spell a likely end for his career in Hong Kong. The reasons for the rejection of Mrs. Singh’s HKSAR passport application remain a mystery, and the Immigration Department has not given any explanation. The couple is unsure what to do next or whether to apply again.

Singh’s story, as it turns out, is not unique. One would assume that Hong Kong permanent residents automatically get HKSAR passports—but this is only the case for ethnically Chinese Hongkongers. Whether or not they are born here, non-Chinese residents have to naturalize, which involves paperwork and a series of interviews. More importantly, though, to be granted a Hong Kong passport, they have to renounce citizenship in their countries of origin. This system creates a curious situation: even people who have lived in Hong Kong all their lives cannot get passports unless they go through the naturalization process.

Hong Kong’s unusual passport policies have a complicated legal background. “We are governed by the nationality law of the People’s Republic of China, which was enacted in 1980. It stipulates that any person born in China, whose parents are both Chinese nationals, or one parent is a Chinese national, should have Chinese nationality. So, China’s nationality law is operated on the basis of blood, rather than place of birth,” explains barrister Dennis Kwok of the Civic Party. “The situation we have is very much governed by the nationality law of the PRC, not by domestic legislation in Hong Kong.”