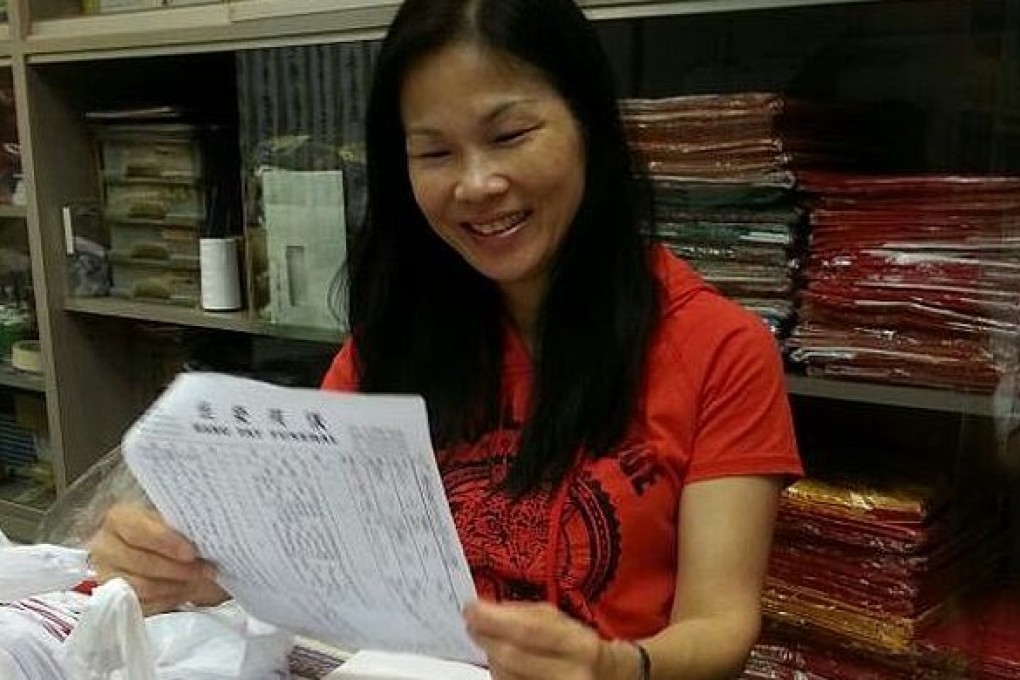

Funeral Director Fanny Leung

If you’ve had a family bereavement, then funeral director Fanny Leung can help to ease the transition for dead and mourning alike. She tells Kiki Elijandy about ceremonies, Chinese burial customs, and the occasional ghost.

HK Magazine: How long have you been working with the dead?

Fanny Leung: I started my business around 20 years ago, but I’ve been working in the field for over 30 years. My father, who had been in the undertaking business since 1952, introduced me. He has had a major influence on me, but I believe it is fate—a feeling that pen and paper simply can’t describe—and also passion that has driven

me to continue what I do.

HK Magazine: What is the significance behind a funeral?

FL: I personally think that a funeral is merely a procedure. It doesn’t matter which belief is practiced: this is a ceremony to express the family’s filial piety. Their significance to the ceremony is the story behind how the deceased came to their belief during their lifetime, and can enter into their afterlife without burden and sin.

HK Magazine: Can you walk me through the procedure?

FL: Every family practices different beliefs with their own traditions, and my job is to plan a funeral accordingly. It starts with picking a “good” date. According to Chinese culture, to be able to pick a good date doesn’t depend on our own business, but on what is auspicious for the deceased. A Christian family’s memorial service will be held in a room surrounded with wreaths symbolizing a circle of eternal life. The ceremony is usually simple with many rituals and a pastor present, to bid the loved one into God’s care. On the other hand, a traditional Chinese Taoist or Buddhist ceremony will have a monk reciting scriptures as the main emphasis, with incense-burning and burning paper offerings as a sign of respect. Flowers, in this case, are only seen as a decoration. The following day, the monk will take the eldest son to “mai sui” [literally “buy water,” a mourning ritual]. This water is used to cleanse the deceased’s body, for them to enter paradise in their purest form. The whole procedure will end with a cremation or a burial, while the paper offerings will be burnt on an annual remembrance day or the Ching Ming festival.

HK Magazine: It’s got to be a tricky job, with all these ceremonies.

FL: The difficulties I have encountered are not because I can’t fulfill the requirements of my client, but in dealing with the emotional aspect of how to ease the pain of the deceased’s family members. I think being able to die at an old age in the presence of family members is a true blessing, but on many occasions this may not happen. But I am very happy to face different challenges each day, and I get great satisfaction from helping others to face the pain by sharing my experiences.

HK Magazine: Tell me about Chinese funeral customs.

FL: Locals have certain traditional Chinese practices. For example, you should not be present when your loved one enters the coffin; nor during their cremation or burial ceremony. Another is that you shouldn’t visit anyone’s home for the first 100 days after a family member’s death, simply because you wouldn’t want to bring your “bad luck” to someone else.

HK Magazine: Is it spooky, dealing with dead bodies all the time?

FL: Yes, I have been scared—because I believe in the presence of spirits and supernatural figures. Hence, all these years I have insisted on running the business under strict principles and I do my best when organizing every funeral that comes to us. If I don’t, I will have to bear the consequences upon my own life.