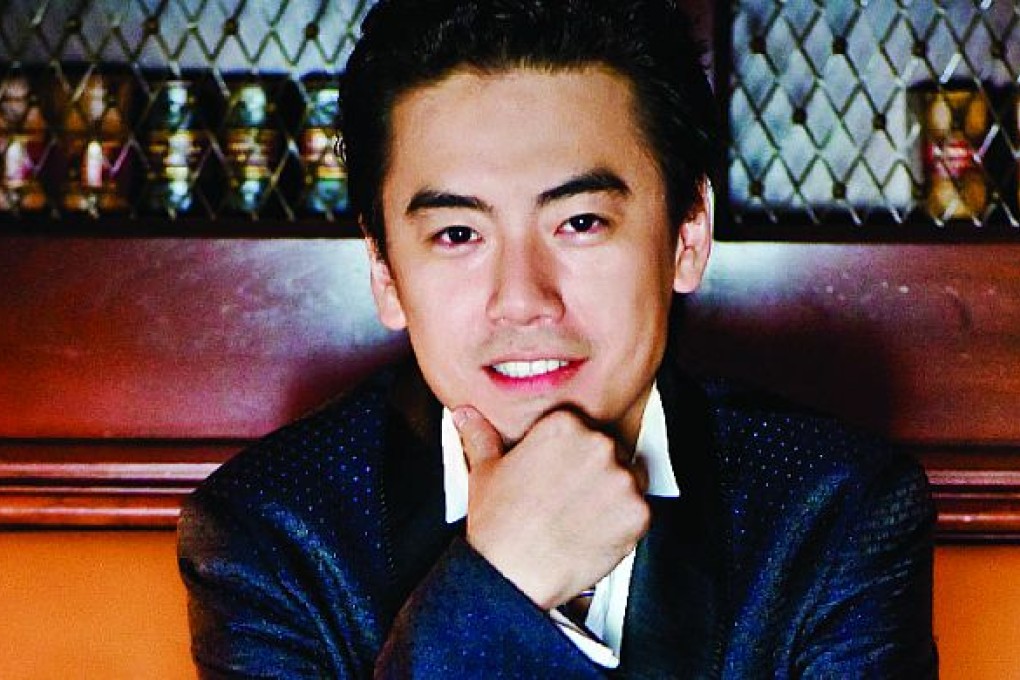

Jing Wang

When the Hong Kong Philharmonic launches its new season next month, the concertmaster’s duties will fall to Jing Wang—a 28-year-old violinist born in Guangxi province and raised in Canada. In a performative art dominated by prestigious foreign acts, critics are already buzzing about what a Chinese concertmaster will do to help promote the orchestra in the mainland. Wang sits down with Christopher Cheung to discuss his upbringing, Hong Kong, and the trouble a violin can cause in Russia.

HK: For our readers who may not be familiar, what does a concertmaster do?

Jing Wang: The term “concertmaster” refers to the principal first violin. In one simple sentence, I’m the messenger between the conductor and the orchestra. As an orchestra, we try to translate the movements from the conductor’s baton to the sound that we create, and I ensure that we do it in the same way as the conductor hears it in his mind.

HK Magazine: How did you get your start playing violin?

JW: When I was three years old, I saw my cousin practicing the violin at our weekly family gatherings. I always wanted to touch his instrument but he wouldn’t let me, so when I got home, I took two chopsticks and imitated my cousin’s movements. My parents realized that I was interested and my dad bought me a small-sized violin from Shanghai. I started learning the violin for the first time at the Guilin Children’s Palace.

HK: How did you go professional?

JW: Well, it happened pretty naturally. When I was five, my family left China and moved to Marseilles. A teacher at the Conservatory there heard me and was interested in giving me private lessons. Later we moved to Canada, and at the age of nine I won a competition with the Quebec Symphony Orchestra, where I played my first concerto. I also got a new teacher in Canada who entered me into many competitions. Before I knew it, I was performing all the time and everything else just became secondary. I didn’t have to choose what I wanted to do as a teenager—I just wanted to play the violin and perform.

HK: You’ve had very diverse performance resume. Do you prefer playing solo, chamber music or with an orchestra?

JW: I think every classical musician has gone through the same kind of evolution. Once you start learning the instrument, you start participating in solo competitions and developing a solo repertoire. My career was very much solo-oriented before, but I play a lot of chamber music too. I’ve performed in Europe, in Canada, in the States. It wasn’t until my last year of school that I wanted to settle down. I started auditioning for orchestras and I was only interested in a chair position. Everyone has to go down the same path, learning everything and being versatile.

HK: Do you anticipate facing any new challenges working here in Hong Kong?

JW: I’ve only worked with American symphonies, where language is not a barrier, so I’m a bit worried about working overseas in Asia. I just hope that it will be easy to convey the message using English during rehearsals. It is a part of my job to relate the message quickly to everybody, and you can imagine how hard it is with 90 people in the orchestra. But something tells me that I shouldn’t be worried.

HK: Do you think there is a big enough market in the Chinese-speaking world for classical music?

JW: Definitely—I think there is even a big enough market for classical music here in Hong Kong. The last time I was here attending a concert, I saw people with a music score in front of them, listening and following along. You would not see that in Europe or in the United States. It’s just very attentive. I can’t say it’s like that in every city in Asia, but I was very surprised at what I saw.