Sex, Money, Food, Politics: How Hong Kong's Humble Fishball Defines Us

Forget the bauhinia, the skyline or the cha chaan teng. There’s only one thing that really represents Hong Kong.

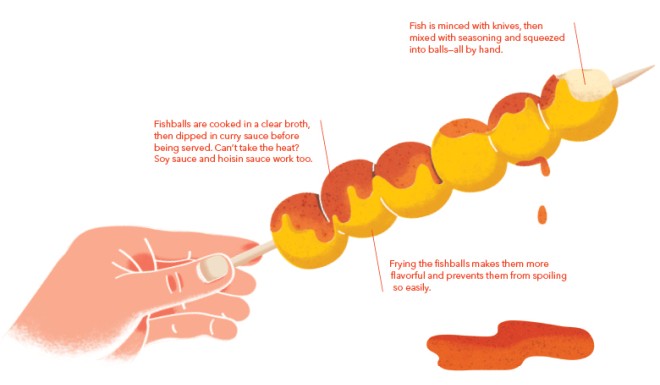

The story behind a skewer of fishballs dipped in curry sauce is the story of what makes Hong Kong special. Originally from Chiu Chow and Fujian provinces, fishballs have been a popular dish in Southern China since the Qing dynasty. But it was Hong Kong which made them internationally famous. At first, fishballs in Hong Kong were served closer to the Chiu Chow style—white and boiled—to pair with noodle soup. But to make the fishballs even more flavorful, Hongkongers started to fry them, giving them a golden coating. Fried fishballs were first popularized by street hawkers, who sold them amongst other snacks from wooden trolleys. But while most street hawkers have been taken off the streets, the fishball has lived on, an enduring symbol of the city. In our food, our economics, our culture—and our politics, the fishball is Hong Kong.

Part 1: The Balls

There’s more than one way to ball a fish. Here’s a peek at some of the best recipes in town.

Fishball & Co.

At Tak Hing Fishball Company the fish paste is freshly made by hand every morning, from croaker and Asian swamp eels. Tak Hing’s owner Lam Lo-ping, aka “Ping Gor,” tells us that the secret tip for getting a smooth and soft texture is to constantly pour ice onto the fish paste, as the heat from all the kneading and mixing stops the paste from gluing together. All that hard work pays off, because there’s a big difference between fish paste that’s been hand-kneaded and balls that have been machine-molded. Machine-molded balls tend to lack the firm bite of a hand-made ball. Tak Hing insists on a no-flour and no-additive recipe—90 percent of their fishballs are meat, and the rest is seasoning. “Those with flour do not qualify to be called fishballs,” scoffs Ping Gor. “The stamina of Chiu Chow people is probably the key to making fishballs,” he says. “It’s a lot of hard work, you know.”

See the man in action and bring home some freshly made fishballs at Tak Hing, where you can also pick up curry fishballs and homemade curry sauce. Can’t get enough of them? Their fishballs are also available at Woo Cow Hotpot (1-2/F, China Insurance Building, 48 Cameron Rd., Tsim Sha Tsui) and Kam Ho Restaurant (91 Lion Rock Rd., Kowloon City). 76 Fuk Lo Tsun Rd., Kowloon City, 2382-0646.

Fishy Secrets

Wong Yim-hing of Wong Lam Kee Chiu Chow Fishball Noodles has been making fishballs for over 40 years, ever since he started helping out his brother in the 70s. His fish paste is made from the “three treasures of fishballs”—conger-pike eel, flathead grey mullet and croaker. Every morning he makes over 100 catties—more than 60kg—of fresh fishballs. Wong also keeps his fish cold to avoid breaking up the proteins in the paste. But cold as it is, the workers refuse to wear gloves when handling the ice-cold paste, so they get a better sense of its texture and stickiness with their fingers. Later, the paste is hand-squeezed into balls, which introduces air into the mixture and creates a fluffy fineness. Sometimes chopped spring onions are added for an extra herby note. Wong’s idea of a good fish ball? Crunchy, smooth and al dente. Check, check and check. Shop A, 10 Shau Kei Wan Main St. East, Shau Kei Wan, 2886-0068.

Part 2: The Sauce

There’s something magical about fishball sauce that keeps us coming back for more. And more.

Sweet Sauces

Sai Wan Ho’s Tai On Building is stuffed full of street food stalls, with everything from Japanese takoyaki balls to Taiwanese shaved ice. But fishball lovers will be familiar with Yu Dan Lo (“Fish Ball Guy”), which has gained quite the reputation for its highly addictive sauce, made from a secret recipe of more than 10 ingredients that the vendor refuses to reveal. All we know is that it’s mixture of satay and curry, and the fishballs are sold out before 8:30pm every day. While the thick sauce lacks the spicy tang that many foodies call for, it’s graced with a lingering sweetness that can be found in no other stall. Shop B, A28, G/F, Tai On Building, 57-87 Shau Kei Wan Rd., Sai Wan Ho. $5 for five fishballs.

Some Like It Hot

If you’ve really got the hots for fishballs, then you shouldn’t miss Sun Kee Cart Noodles, which has risen to fame thanks to their super spicy sauce. Again, the sauce is a secret, but it’s worth the trip. You feel the heat at first bite, a spiciness that gets the tastebuds tingling without covering the original flavor of the fish. But it’s not just spicy: a satay-style aroma keeps us coming back for more. Shop B, G/F, 49 Tang Lung St., Causeway Bay, 2573-5438, $10 for five fishballs.

Part 3: Fishballs Deep

But fishballs aren’t all tasty treats. The Cantonese phrase yu daan mui, “fishball girls,” refers to minors, usually schoolgirls, who allowed punters to grope their bodies in exchange for money in the 80s. Squeezing a yu daan mui’s barely-developed breasts was said to be similar to squeezing fishballs. These girls didn’t work at fish stalls, but in upstairs tearooms which were referred to as “recreation centers.” Just like compensated dating nowadays, sex was not in the package but was often implied.

The term came to light when David Lai’s 1982 film “Lonely Fifteen” blew our minds with its ruthlessly candid depiction of Hong Kong’s sex industry. Lead actress Becky Lam won Best Actress at the Hong Kong Film Awards for portraying a runaway who ended up as a fishball girl. This (supposedly) touch-only form of prostitution passed out of fashion when one-woman brothels became popular in the 90s.

Part 4: Fishballonomics

Hong Kong doesn’t need complicated economic indicators: Fishballs do the trick just fine.

Causeway Bay is notorious for being one of the most expensive retail areas in the world, but nothing tells the story better than fishballs. Back in 2008, Singaporean pork jerky chain Bee Cheng Hiang forced a street food vendor out of its prime location on Causeway Bay’s Sogo intersection by forking out about $330,000 per month for the tiny space, around three times what the fishball stall was paying. If the fishball sellers had stuck to that location, they would have had to sell around 1,571 fishball skewers a day to cover the rent.

This year, at the Lunar New Year Fair in Victoria Park, wedding banquet and restaurant group ClubOne paid a record $630,000 for a 392-square-foot stall to sell abalone and fishballs during the week-long event. Two other snack vendors paid $450,000 or more for their stalls. With rent like this, ClubOne would have to sell 9,000 fishball skewers a day, at $10 each, for the seven days of the festival, just to break even—and that’s before considering other overhead costs.

So much for cheap eats.

Part 5: Fishball Revolutions

Fishballs have become so inseparable from Hong Kong identity that they dubbed the Lunar New Year Mong Kok unrest the “fishball revolution,” even though fishballs had very little to do with the riots. But this isn’t the first time that fishballs have stoked unrest.

Reason to revolt?

When Financial Secretary John Tsang announced his 2015-2016 budget, he toyed with the idea of introducing food trucks selling street food classics such as beef offal and fishballs. The city’s hawkers, already operating on rapidly dwindling licenses, would have to pay an estimated $600,000 in start-up costs for a food truck.

Mother-tongue-tied

A parent told Ming Pao newspaper in January this year that in a school writing assignment, her daughter’s teacher had instructed her to use the Putonghua word for fishballs—yu wan zi—instead of its Cantonese counterpart. Encroaching influence from the mainland, or just good written Chinese? You decide.

What a Load of Ball-ocks

During a 2013 legislative hearing into former anti-corruption chief Timothy Tong’s alleged lavish spending on gifts, entertainment and official visits, Tong claimed that he acted in “courtesy of reciprocity” when he bought a visiting Mainland delegation a $815 gift of beef brisket and fishballs. Guess dinner’s on Tim tonight!

Part 6: The Fishball Anthem

With fishballs having conquered the city’s culinary, economic, cultural and political identity, there’s only one way to go: We need a new anthem, a new symbol of our fishball city. Fishballs Forever! May the sun never set on this curry-sauced empire!

Fishballs, fishballs, ever glorious

Sign of Hong Kong’s will and might!

Dipped in curry, served with noodles

Sold by hawkers in the twilight!

Please don’t take our fishballs from us

Or we’ll hit the streets tonight…

Yu daan man sui!

Fishballs Forever!