Chinese Typewriters Exist, and Tom Mullaney Wants to Save Them

Yes, they exist. Yes, they're awesome—and they could be coming to Hong Kong

Stanford University professor Tom Mullaney is on a mission to rescue the the Chinese typewriter from the scrap heap. Over the past decade he's built a collection of the underrated machines, and now he's launched a Kickstarter project to bring his collection to museums around the world—Hong Kong included.

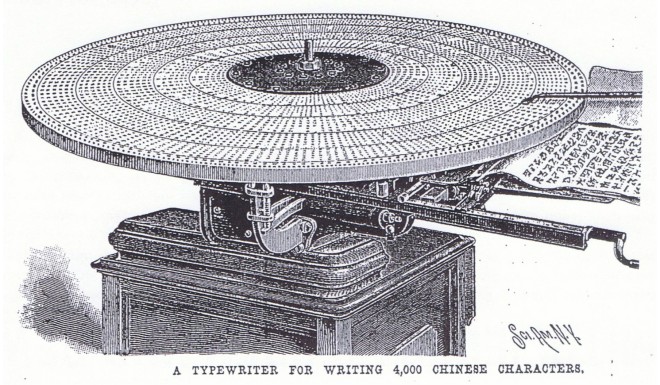

What inspired you to study Chinese typewriters? The Chinese typewriter flies in the face of more than 100 years of conventional wisdom, and so does the history of modern Chinese information technology. When we look at Chinese IT and the Chinese language now, we see a world that many in 1900 considered impossible: A vibrant, modern IT world based on Chinese characters, which are one of the fastest, most widespread, and successful languages of the digital age. This would shock the many people who, for the past two centuries, assumed that such an outcome was conceivable only if China got rid of character-based writing and went the route of wholesale alphabetization. The answer to this outcome can be found by studying the most “seemingly impossible” information technology of all: The Chinese typewriter, an object many thought it would be impossible to build.

So what does the success of the Chinese typewriter mean? I think it calls for a rewrite of the entire history of IT as we know it. In sharp contrast to the popular idea that “winners write history,” in the case of modern Chinese language reform, it is the losers of history who have managed to command the greatest attention of scholars: Historical figures like the famous writer Lu Xun, or co-founder of the CCP Chen Duxiu, who were famous for advocating the abolishment of Chinese characters.

By contrast, we know virtually nothing about the “winners” in this story: The brilliant engineers, linguists, entrepreneurs, and everyday individuals who actually built China’s contemporary information environment. Unlike their celebrated and well-known abolitionist counterparts, the actual builders and users of the modern-day Chinese information infrastructure—now the largest IT market in the world—never appear on undergraduate course syllabi about China. Indeed, they were often anonymous even in their own times. My hope is to tell the story of China’s real iconoclasts.

Why exhibit now? There are literally hundreds of museums dedicated to the history of the Western typewriter and to Western IT, but there is not a single museum dedicated to the Chinese typewriter, or to the history of modern Chinese and East Asian information technology. So, when researching the history of Chinese IT, I had no choice but to build an archive from scratch. This past January, the opening of the “proto-exhibit” at Stanford University was wonderful and very encouraging. The event was full of conversation and curiosity: Despite all of the distortions and misrepresentations of Chinese information technology in pop culture, people are very open and eager to learn about this fascinating chapter in the history of language and technology.