The British submarine that sank off China and the Hong Kong sailor who, against the odds, escaped the wreck - then vanished

All but one of those who survived being trapped on the sea bed in the 1931 HMS Poseidon disaster were lauded for their courage. Cruzanne Macalister goes in search of an unsung hero from Hong Kong

The sea has produced many heroes. Some are celebrated, revered and live on for years in stories passed down for generations. Others remain unrecognised, left out of official records and overshadowed by the accomplishments of counterparts.

Ah Hai, an officer's steward from Hong Kong, is one of the latter.

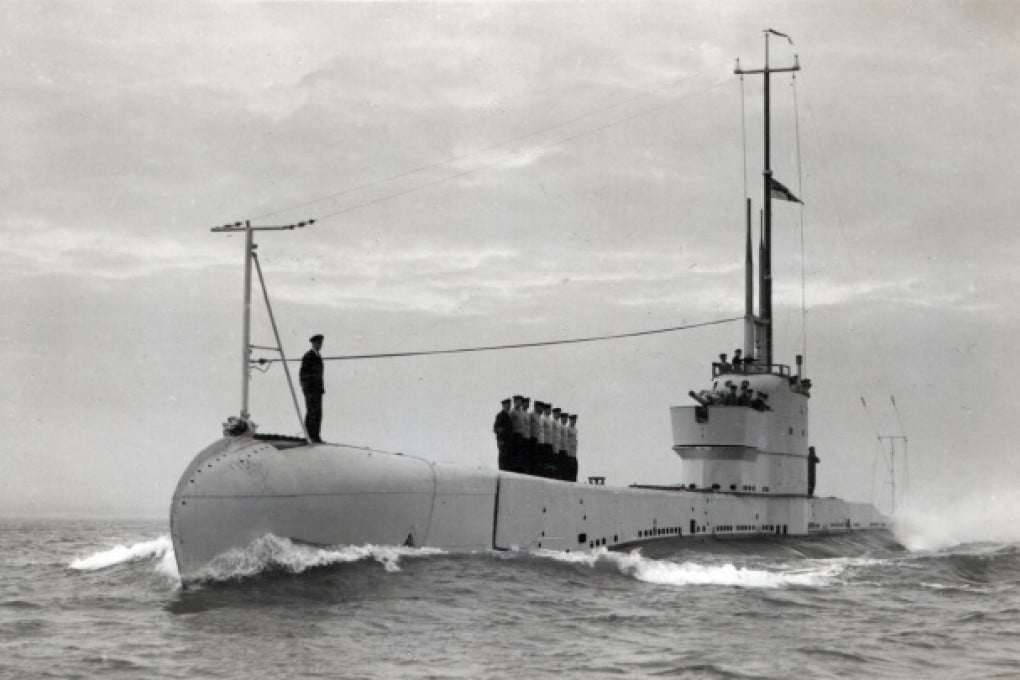

of June 9, 1931, the HMS Poseidon, a Hong Kong-based P-class submarine with a crew of 53 and the pride of the British Royal Navy fleet, set off from Weihaiwei (present-day Weihai, Shandong province, which until 1930 had been a British colony), where it was taking part in a routine torpedo training operation.

The hardworking submariners had left the heat of Hong Kong behind and would have welcomed the respite in the cooler waters of Weihai, where it would have been possible to ventilate the vessel more efficiently.

It was to be a straightforward operation but, when the Poseidon was getting into position to fire a dummy torpedo at the HMS Marazion, something went wrong. As the Poseidon surfaced, she found herself in the path of a Chinese freighter, the SS Yuta.

The Yuta struck the hull of the Poseidon, carving it open. The order was given to abandon ship and those who could scrambled up the conning tower to escape, to be hauled aboard the freighter.

For those in the engine room, though, there was no time; they would have probably been drowned by the in-rushing water very quickly. However, having followed orders to close watertight doors, a group of eight men found themselves trapped in the forward torpedo compartment.