Friend or faux?

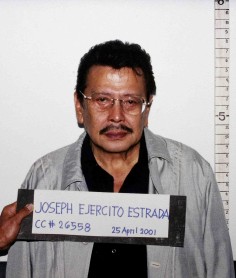

Actor turned politician Joseph 'Erap' Estrada, who was ousted as president of the Philippines in 2001, is back in a new role. But will the newly installed mayor of Manila fulfil his promises to the poor, asks Raissa Robles

On his first day as mayor of the nation’s capital, deposed Philippine president Joseph “Erap” Estrada seemed to be in no hurry to meet the people who had elected him and were swarming outside his office. The day before, while being sworn in, Estrada had made a promise: “Here in Manila, the poor are the boss of Erap”.

Many, like Marina Palin, 72, had walked the three kilometres to City Hall from the poverty-stricken district of Tondo in the sweltering July heat in order to hold Estrada to the campaign pledges he and his running mate, Vice-Mayor Isko Moreno (a screen name – the former movie actor’s real name is Francisco Domagoso) made to the poor.

“I want to ask Mayor Erap for help because I was hit by a motorbike and I can’t ask the man who hit me because I pity him. He has many children,” Palin tells Post Magazine. “I’m also going to ask Vice-Mayor Isko for a cart for the fruits I sell.”

Fellow Tondo resident Luzviminda Laylay, 48, says she wants to ask “Presidente Erap” to give her back the hospital job she lost just before the elections.

The driver of a jeepney (the uniquely Filipino minibus), accompanied by his wife and child, waves around a traffic ticket, saying he was slapped with a fine of 2,000 pesos (HK$358) – which he cannot afford to pay – for arguing with a policeman. He wants “Presidente Erap” to hear his side of the story and scrap the fine.

Another man pleads to see Erap – the nickname means “friend” – because he has not been paid the 100,000-pesos bill for the medical equipment four city hospitals bought from him. An ageing movie stuntman who took a real bullet for the former action-film star when things turned ugly following the revolution of 1986, claims the mayor promised him a job.

Manila’s City Hall – inaugurated in 1941, when Estrada was four years old and growing up in the affluent part of Tondo – is the shape of a coffin. The mayor’s office extends around the top; a small door to one side provides a discreet exit.

“The president is busy with meetings,” says the lone policeman guarding that door, as the crush of expectant people, including journalists, reconvenes outside.

Estrada’s aides, who pop in and out, also refer to the new mayor by his former title – one he lost in January 2001, when a military-backed popular uprising nudged him out of the presidency following allegations of massive corruption. On the door is a colourful poster put up by the previous administration depicting a fat man in a blue shirt gorging himself on burgers while playing the popular computer game Plants vs Zombies. The cartoon is stamped “City Personnel Office” and has the caption: “Are you this person? The lazy aren’t allowed here. Do your duties.”

The resemblance of the figure in the poster may be coincidental but, during Estrada’s 2½-year presidency, it was he who was branded lazy, especially when compared with his workaholic predecessor, Fidel Ramos. Estrada famously said, when foreign visitors had been kept waiting for nearly an hour: “The president of the Philippines is never late. His guests are early.”

The image of a carousing, overweight president became imprinted on the nation’s consciousness in 2000, when Aprodicio Laquian, chief of staff at Malacanang Palace (the president’s official residence and workplace), told the media that, “at four o’clock in the morning, I am the only person sober in the room”.

He was referring to Estrada and his cronies, who, he suggested, made the president sign papers. Laquian congratulated himself for not drinking because, “If there is one person who is sober in the room who would be able to take all of these things that were signed and hide them in my record book, then the decision-making will probably be, in the beautiful light of the morning, very rational.”

Laquian was fired by a furious Estrada hours later.

IN AN EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW, however, the new mayor tells Post Magazine that his late-night soirees are a thing of the past. “I’ve changed,” Estrada says. “I always go in the morning to the office.”

He apparently adopted his nocturnal routine while shooting movies overnight (and having to sleep during the day). So, how was he able to break the habit of a lifetime? Estrada told a news daily that he had been injected 14 times with the blood of unborn sheep in a German clinic in April. This procedure reportedly enabled him to, for the first time in many years, sleep through the night. He even brandished a brochure for the Frankfurt clinic, which boasted about its other stem-cell-therapy patients, including Nelson Mandela.

Estrada tells Post Magazine that he has something else in common with South Africa’s iconic freedom fighter, as well as with the opposition leaders of Myanmar, Aung San Suu Kyi, and Malaysia, Anwar Ibrahim. All were imprisoned “because of politics … that is why we are known as men of conviction. I’m in good company”.

Estrada insists he was wrongly convicted of the capital crime of plunder. His sentence included the forfeiture of 734 million pesos deposited in two bank accounts – one under the dummy name Jose Velarde – and seizure by the state of a 7,145-square-metre property called the “Boracay mansion” (so named for the sand that was transported from the holiday island to surround the home’s swimming pool). Estrada reportedly gave the palatial building as a “gift” to the second of his six mistresses, who have collectively given him at least 11 children.

To this day, Estrada insists he did no wrong and therefore has nothing to apologise for.

Earlier this month, however, a former top judge who played a role in ousting Estrada hinted that the politician might have a different definition of corruption to most: receiving “commissions” and illegal gambling pay-offs do not qualify.

The ex-convict considers his poll victory in Manila a vindication and a “not guilty” verdict by the electorate over the Charges, for which he was placed under house arrest.

However, by the same reasoning, Estrada must have been judged “guilty” in 2010 by the national electorate, which rejected his bid to become president again.

No one expected him to run for mayor because the post is a big climb down from the presidency. Nonetheless, his victory is remarkable for someone who was convicted and sentenced to up to 40 years in jail. And the mayoralty of Manila is still one of the country’s most powerful positions. Malacanang Palace, just a short ride from City Hall, is under his political jurisdiction.

Sources say Estrada won because he managed to grab Domagoso as running mate from incumbent mayor Alfredo Lim. While Estrada merely pretended to be poor in movies, Domagoso is the real deal – he was born into poverty in vote-rich Tondo.

To win the race for mayor, Estrada made all sorts of promises, even assuring an animal rights group he would send Manila Zoo’s lone elephant, Mali, a female from Sri Lanka, to a sanctuary in Thailand.

“It is not right for people, especially children, to see lonely, ailing and depressed animals living in deplorable conditions,” he wrote to the People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals Asia.

Now, though, he says, his plans for Mali have changed. She will remain in Manila Zoo “but Sri Lanka [through its ambassador] is going to donate one elephant to keep him [sic] company” under a public-private partnership programme.

MAYOR ESTRADA BEGAN HIS FIRST day in office armed with a broom. He led a symbolic sweeping of the streets to rid the city of grime, traffic and crime, in order to attract tourists and investors. Estrada blames Lim for having scared away tourists through his mishandling of the August 23, 2010, hostage crisis, which left eight Hong Kong holidaymakers dead.

“Maybe I’ll apologise [to Hong Kong] on behalf of our government [because] there was a mishandling of the crisis,” Estrada says. When asked if he would hold a ceremony next month and invite Hong Kong officials to it, the mayor says, “Well, I’ll think about that.”

Unlike Lim, Estrada is welcome in Hong Kong, where he had knee surgery in 2008.

Estrada then makes a startling disclosure: “I have a document from the late [interior and local government] secretary Jesse Robredo recommending a one-month suspension of Mayor Lim [as punishment for bungling the hostage incident]. But, sad to say, it was not implemented.”

Robredo died when the plane he was travelling in plunged into the sea shortly before last year’s second anniversary of the hostage crisis.

During the ceremonial broom-sweeping, meanwhile, Estrada for the first time sounded a note of caution to the poor – his “bosses”: “I am not Superman and I know I cannot immediately solve all these [problems]. And so I ask you to endure and sacrifice a little more; to have a little more patience and understanding; and, most of all, to give me your whole-hearted concern and involvement.”

Perhaps endurance and sacrifice were what he was looking for, then, when he avoided coming face-to-face with the poor who had congregated outside his office later that day.

“They are expecting so much from me,” he says. “But, you know, we don’t have the funding right now. We are trying to recover.” Lim left City Hall bankrupt, he adds. “Right now we are short of cash … we have a deficit of 11.55 billion pesos.

The culprit is an obvious one: “Corruption is all over. From the police down to the last civilian employees.”

He says he plans to increase revenues by computerising tax collection.

“I would say, intentionally or not, you know, how come there’s no computer in City Hall?

I was the first mayor to computerise” property tax collection (during his stint as mayor of the Metro Manila city of San Juan, from 1969 to 1986). According to Commission on Audit reports, Manila had 1.9 billion pesos in uncollected property taxes in 2011.

AN AIR OF NEGLECT hangs around City Hall. Small piles of rubbish have gathered in odd corners. Some electric wall sockets have burn marks on them. There is a small plastic container in the middle of the floor of the grand central hall, which boasts an ornate chandelier, to catch rainwater leaking through a crack in the ceiling.

As Estrada busies himself with meetings on his first day and the poor patiently wait for him outside, other, well-dressed, visitors start to trickle out. With their smart clothes and swaggers, these men do not look like your average City Hall employees.

A waiting Tondo constituent remarks that some are probably friends of the mayor who have come to congratulate him.

Friends have often been Estrada’s downfall. Domingo Siazon, a schoolmate and his former secretary of foreign affairs, wrote in a book presented to Estrada as a birthday gift last year: “The term of President Erap had been cut short by EDSA II [the revolution that overthrew him]. I would blame this on his many friends who failed to distinguish Joseph Ejercito [Estrada’s real name] from President Erap. They took advantage of his loyalty and kindness.”

Margaux Salcedo, his spokeswoman and author of the book Ito ang Pilipino (literally “This is a Filipino”): A Tribute to Joseph Ejercito Estrada, wrote: “It is unfortunate that the scandals wreaked by the indiscretion of some of those closest to him cost him his presidency.”

Despite past failures, however, and his reluctance to meet his supporters from Tondo, hopes are high for the mayor of Manila.

“He loves Tondo very, very much and we love him, too,” Palin says.

At noon, the policeman guarding the door throws it wide open and tells the waiting crowd, “President Erap has left.” Meekly, the crowd disperses.

Some among the throng mutter about the policeman and aides not having told Estrada of their presence.

“Erap would not do this to us if he knew,” says one.