Then & now: The joke's on you

Racial stereotypes were a comedy staple until the turning tide of public opinion revealed some uncomfortable home truths, writes Jason Wordie

Certain stock comic figures remain instantly recognisable across cultures and time periods. Caricatures based on physical peculiarities, such as gross obesity, have been the butt of jokes since pre-ancient times. Country bumpkins, and their reactions to city life, provide another familiar stereotype that crosses ethnic boundaries.

Inter-war Chinese films often featured a Kam Shan ah baat ("Gold Mountain uncle"). The phrase has its roots in the mid-19th century gold rushes, which saw thousands of Chinese immigrants seek their fortunes in North America (mostly California), Australia and Southeast Asia. California was known as Kam Shan, although in the Pearl River Delta, among people whose knowledge or experience of the world didn't extend much beyond their own district, anywhere in the wider world was "Gold Mountain", too.

Emigrants to Southeast Asia, due both to geographical proximity to China and, in places such as Malaya and Singapore, sheer numbers, remained more connected to their native country. Kam Shan people were more cut off and became Rip Van Winkle-like on their eventual return home. As a returning emigrant, then, the Kam Shan ah baat was a classic country hick made good. Such individuals simply had to let everyone know they had done very well indeed in foreign parts and possessed more money than they knew what to do with. And - this was the punch line - they became an easy touch for every hard-luck story and get-rich-quick scheme.

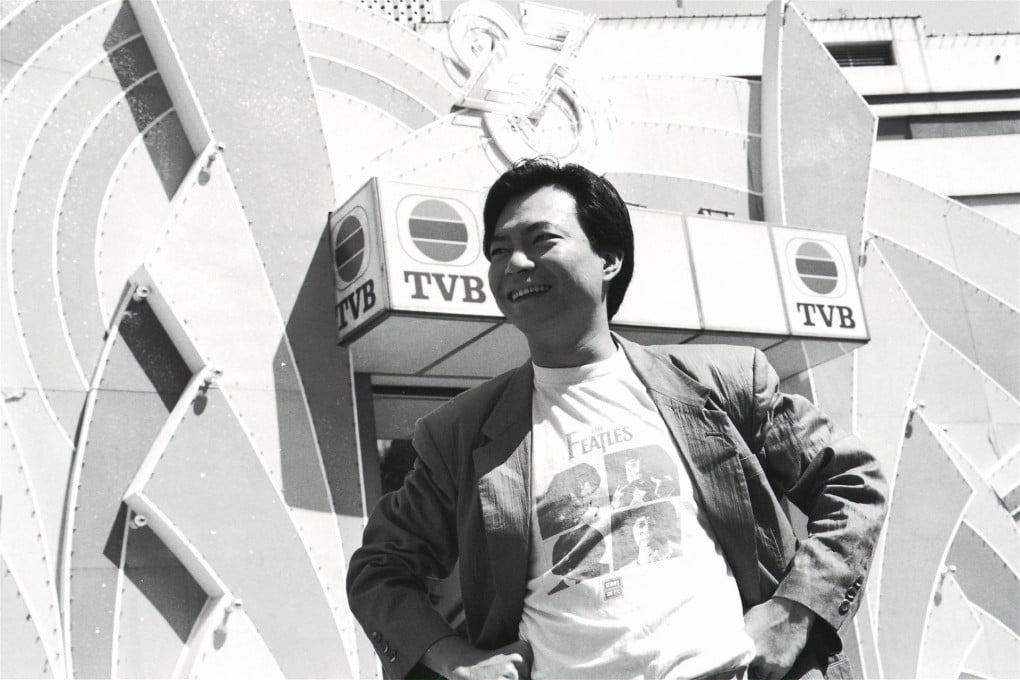

"Ah Chan", the rough-edged, idle hick played by Liu Wai-hung in the 1980s TVB series The Good, The Bad and The Ugly - which crystallised all that Hong Kong Chinese despised, and feared, about mainland immigrants - offered a later, less funny echo of the same theme. Contemporary parallels can be seen among portrayals of emigrants returned from Canada - heavily Westernised and more at home speaking in English than Cantonese, they clumsily feel their way around a Hong Kong Chinese world that has moved on without them. Usually sympathetically portrayed, nevertheless the social faux pas their surface Westernisation begets are sharply highlighted.

Comic figures also reinforce a supercilious condescension - or help create one - among the target audience. In particular, they play into the ethnic superiority/inferiority complexes and identity confusion that have long characterised Hong Kong Chinese society and culture.

One such figure was Maria, the dopey, disaster-prone Filipino maid who appeared on local television in the late 80s, a time when domestic workers from the Philippines were first appearing in the city on a large scale. Elvina Kong Yan-yin, the Chinese actress who played the part on the long-running Enjoy Yourself Tonight variety show, deployed grotesque "blackface" make-up, ludicrous Cantonese and a slapstick manner to great popular amusement. In the process, the character reinforced the nasty sense of cultural and racial superiority lurking among many Hong Kong Chinese viewers.