Affairs of Our Hart

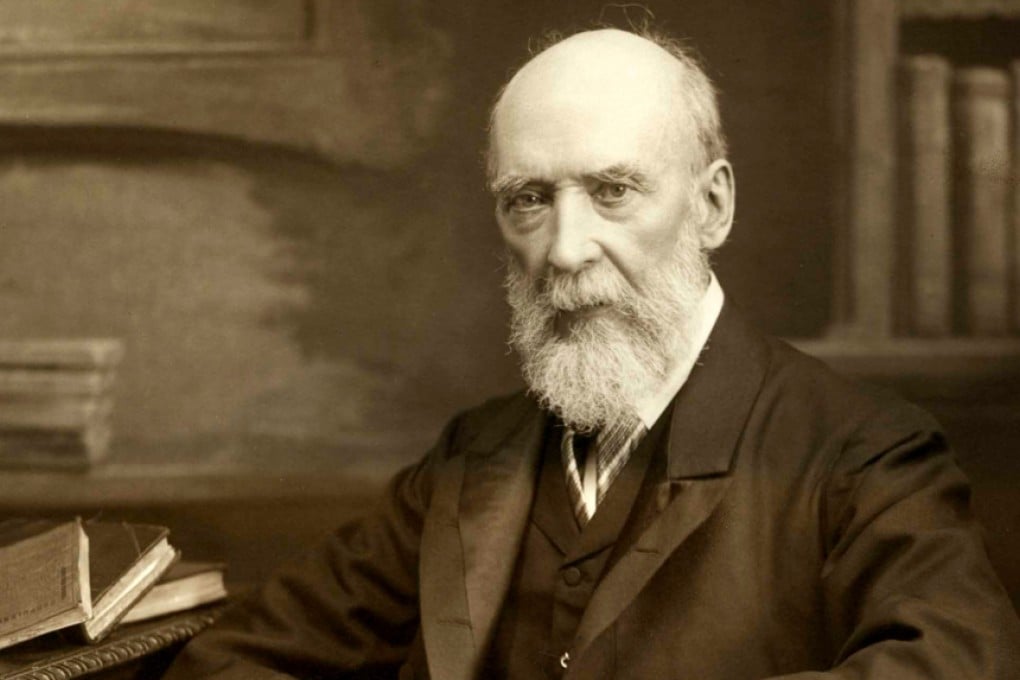

The most influential Westerner in Qing dynasty China, Sir Robert Hart was a man tortured by lust and loneliness.

November 2013 marks the 150th anniversary of the appointment of the man who would become the most influential Westerner in Qing dynasty China.

However, Sir Robert Hart’s private papers – which are to be found in collections in Belfast, Northern Ireland, and London and at the University of Hong Kong (HKU) – reveal a man who paid a handsome price for his glittering career.

Behind Hart’s colossal reputation and achievements during a 48-year tenure as inspector general of the Chinese Maritime Customs Service, the nation’s first modern bureaucracy, is a personal story characterised by repressed sexual desire, forbidden love, beautiful Chinese concubines, illegitimate children, a love of platonic female company and the constant threat of scandal. It retains an intriguing resonance for foreigners living and working in China a century and a half later.

Hart’s huge part in 19th-century Chinese history started, like many others, in Victoria Harbour, into which he sailed in the sticky summer of 1854, a naive 19-year-old Irishman starting work with the British consular service. By the age of 28, he would become the acting head of the most powerful and enduring department of the Chinese government. And apart from a few brief spells in Europe, Hart spent almost his entire adult life in China, before retiring to Britain in June 1908, aged 73.

A street in Tsim Sha Tsui bears his name, but few people working along it seem to know anything about him. Many of the traditional shops on Hart Avenue have been superseded by noisy sports bars, but at a Sichuan noodle shop, the elderly owner sips tea and considers the street name for a moment.

He looks vaguely uninterested and suggests the street was named after some “Yingwok yan” (“Englishman”). Further down the avenue, a friendly young barman pouring pints of Guinness in the crowded Hair of the Dog guesses that Hart must have been an English colonial official and seems amused to hear that, in fact, he was Irish – like the drinks in his hands – and worked for the Qing government.