Then & now: Coffin homes

The Tung Wah Coffin Home provided superior accommodation to that which those in hospital could expect, writes Jason Wordie

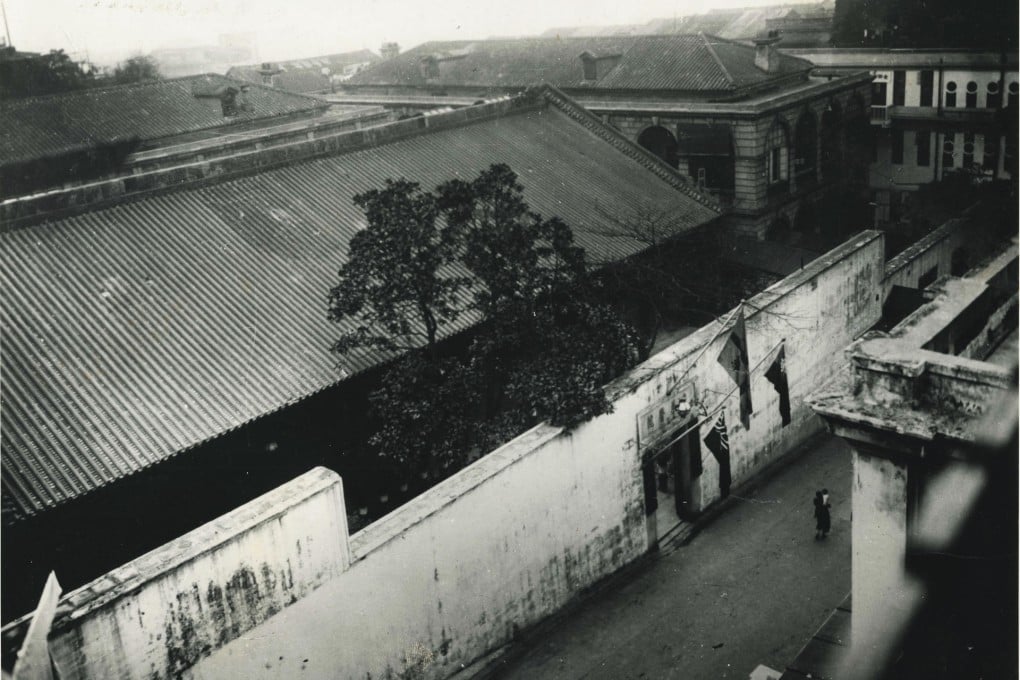

Hong Kong has only one location that objectively qualifies for World Heritage status - the Tung Wah Coffin Home in Sandy Bay. Tucked away above the Pok Fu Lam coast, this pleasing, lemon-yellow group of buildings, surrounded by sprawling squatter huts, nestles in a ravine next to a cemetery.

Only the entrance gate, down a quiet path off Victoria Road, offers some indication of what lies below. Built to manage the repatriation of bones from overseas Chinese communities, the complex represents an enduring regard for the welfare of the dead and tells us much about Chinese attitudes to the overall emigration experience.

"The fallen leaf returns to the root" is one of most common Chinese phrases used to describe the human life cycle. Gold-mining and other employment opportunities saw thousands of Chinese cross the Pacific from the late 1840s onwards. Not all were able to return home in this life, so repatriation of bones to ancestral villages became very important.

Ships returning from California and elsewhere habitually carried boxes of bones. While macabre to Western sensibilities, from a Chinese perspective the practice made complete sense: human life is seen as part of a continuum, with connections between ancestors and descendants an article of faith, and death - while usually a sad (and sometimes tragic) event - a normal part of life. Naturally, one would wish to spend the afterlife in familiar surroundings, close to family members, especially if circumstances had dictated otherwise during one's lifetime.

After a few well-publicised incidents when bones destined for repatriation were dumped overboard during passage (most notoriously off the Australian coast) by ship captains, agents took to travelling with their car-gos to stop the practice. And when the Tung Wah Hospital was set up, in 1870, its charter specifically stated that it was intended for the care of the deceased - until they could be returned to their ancestral birthplaces - as well as the living. The latter expressly came second in terms of importance.

What did this mean in practical terms? In her semi-autobiographical novel A Many-Splendoured Thing, Han Suyin noted the contrast in "living conditions" in the late 1940s: "The brick Coffin Hospital in Hong Kong [was] comfortable, spacious and rainproof, not like the huddle of sheds next to it which temporarily sheltered 180 lepers." The living - very clearly - ranked well below the dead.