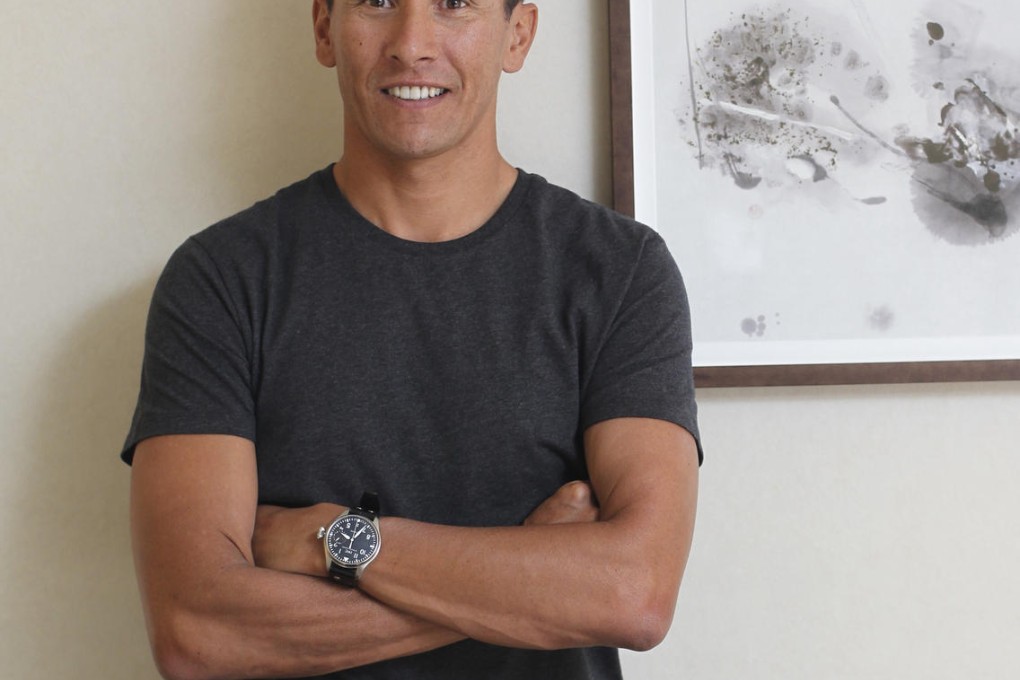

My Life: Chris McCormack

The 41-year-old Australian triathlete and former Kona Ironman champion tells Rachel Jacqueline how he transformed his father's disapproval into pride

I grew up near the beach in southern Sydney, Australia. My brothers and I lived, ate and breathed surfing. I always dreamed of being a professional surfer but my Dad shut down the idea. He was a waterside worker - a "wharfie" - with zero education and Mum was a schoolteacher. Dad was determined his kids would have an education and was completely anti-sport as an occupation.

In my teens I wanted to be a better surfer so Dad said I should start running. It'd make me fitter, he promised, so I ran my guts out. At high school I was good; I won my first state title in cross-country running aged 13, the Australian title at 15 and continued then every year after that. But we had zero idea; I had the wrong shoes - I'd run in Converse. And I was embarrassed - my brothers told me running was geeky. But I loved winning. Coaches said I could go to the Olympics. It wasn't until Dad realised I could pay for my education through running that he encouraged me. I got the Ben Lexcen scholarship at the University of New South Wales (awarded to students of outstanding ability in sport) and studied economics.

I remember watching the 1987 Kona (Ironman) World Championship on TV. It was held in Hawaii, home of the best surf. I got my hands on some triathlon magazines afterwards, but it wasn't until I watched my first triathlon in 1991 that I got the idea to compete. I won my first race and A$500 - a lot for a 17-year-old. Soon after I won the Canberra triathlon. Everyone wondered who I was. They thought I cheated. I went to the Junior World Championships in 1993. I was winning the race and, as I came down the finishing chute, I thought I had it in the bag and stopped to high five people. Three guys ran past me and I ended up fourth. It's been folklore in Australian triathlon ever since. I was offered a contract in the same year to compete professionally, but Dad put his foot down. He insisted I finish university.

After university I worked as an accountant. I remember seeing all these guys on TV whose arses I used to kick, making money and travelling the world while I was stuck in an office. I quit the next day. I didn't tell Dad for two weeks. I'd get up in the morning, put my suit on and he used to drive me to work for a job I no longer had. I flew to Paris two weeks later with A$3,300 to my name. I found races and would compete Friday, Saturday and Sunday. I needed the money. I was so homesick. I spoke zero French and didn't talk to anyone. But I knew if I went home, my brothers would give me a hard time and Dad would have said, "I told you so." I got a lucky break at the 1995 International Triathlon Union World Cup in France. I beat everyone. I was offered a wild card for the next race in Canada. I won that, too. That's when it all started.

By 1997 I was world No1. I came back to Australia to compete in the World Championship in Perth. Dad came to watch when I won. That was the moment; two years of desperation not to disappoint Dad. Just before the second trial for selection for the Sydney 2000 Olympic Games, my Mum passed away. Her funeral was on a Friday and the trials were on the Sunday. Because of the selection criteria, I had to win it. I was devastated; I felt like the worst son a mother could have: I'd been away, I felt guilty. Dad told me to race and I was doing great until someone in the crowd called out, "Macca, do it for your Mum." It broke me. I stopped, sat on the gutter and cried. They didn't select me for the team; they said my head wasn't in it.

After that, I moved to the United States. I started racing like crazy. I had a massive chip on my shoulder. The Triathlon Federation of Australia asked me to compete at the Athens Olympic Games in 2004. After a fight with the national coach he asked me where I was going to go. "Ironman?" He said I was too young. I said, "We'll see." I won my first Ironman Australia in 2002 and defended the title for four years straight. I used to win everything but never Kona. I was too big and it was too hot. Ironman guys are between 59kg and 65kg; I was 78kg. Everyone said it wasn't possible. I started second-guessing my ability. For the 2007 Kona I overhauled my training. I embraced my fear of the heat and trained like mad. I would go to Hawaii and do 30km of swimming, 1,000km on the bike and 130km a week of running on repeat. I used to make myself paranoid and angry. People used to think I was too serious; of course I was serious, it was my life. I played defensively that year and conserved myself. It worked - I won. I always believed I could but it takes a lot of courage to do things differently when you have a working formula.