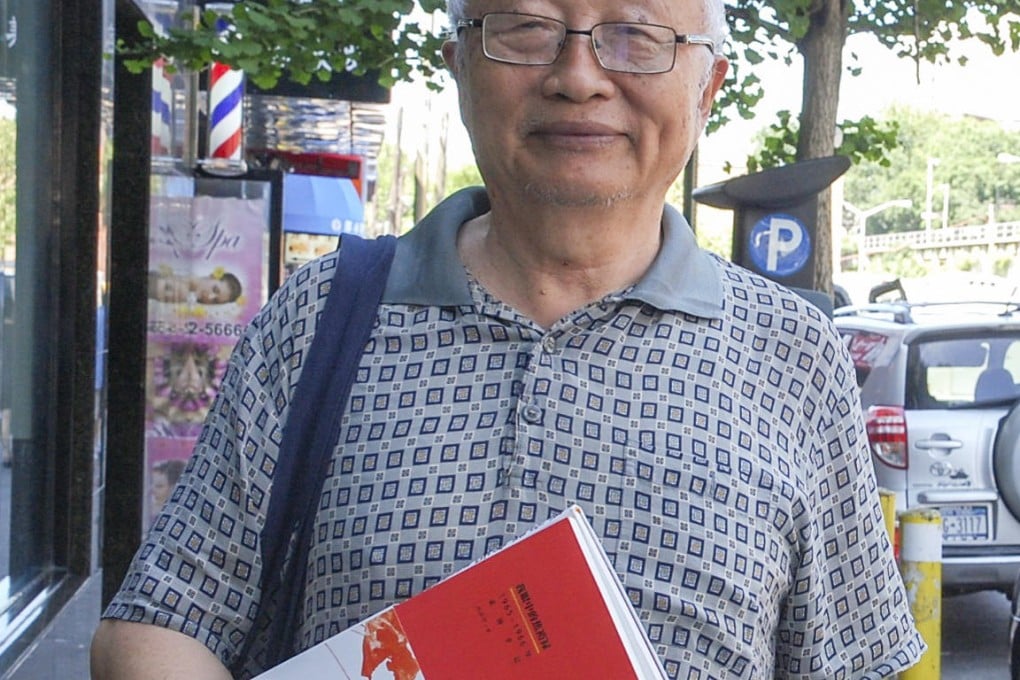

My life: Ren Yanfang

The author of The Jiao Yulu I Knew tells Rong Xiaoqing why he wants to set the record straight about the Communist Party hero

I spend most of my time in New York now, living with my daughter. Last year, when I went back to China for a few weeks, CCTV (China Central Television) was showing a drama series about Jiao Yulu (a Communist Party chief in Lankao county, Henan province, who came to symbolise "the honest cadre"). It was a 30-episode show. I had to stop at the eighth episode because the falsifications drove me crazy. President Xi Jinping went to Lankao twice in the first half of this year to promote the spirit of Jiao. This is the 50th year since his death. But my book's ( The Jiao Yulu I Knew) publication at this time is only a coincidence. I was prompted by the untrue beautifications and exaggerations about him in fictional works in recent years. I want to present a real Jiao to my readers.

Jiao was deployed to Lankao by the party in December 1962, to implement Chairman Mao's call at the 10th plenary session of the Eighth Central Committee to tighten the class struggle, fortify the people's commune and thwart a wave of privatisation. Nowadays, most of the fictional works avoid mentioning this. Rather, they portray him as a leader who initiated land privatisation in Lankao, to bring the poor peasants better lives. Yes, creativity is allowed in fictional work but not in this way, not to pull the characters out of their historical context. I understand the writers may have good intentions; they want to polish Jiao's image. But they end up tarnishing it.

I got to know Jiao in person because of my stepfather, Meng Zhaozhi, who had been a deputy of his in Lankao. My birth father was a communist killed by the Kuomintang during the 1930s. I spent some time with my mother, who was also a Communist Party member, in the army when I was a kid. When my mother remarried and moved to Lankao, I went to visit them for the first time in 1962. I was 25 then and had already graduated from Peking University and become a playwright in the Changchun Film Studio.

Lankao was so poor at that time. When I arrived at the train station, I saw a kid jump an old man from behind and grab the steamed bun he was holding. The old man chased after the kid but the kid had already put the bun in his mouth while running. Everyone there was hungry. Jiao went to Lankao a month after I left. I met him for the first time when I went to visit my family again in 1963. He lived close by. We chatted. He told me he was planning to go back to his hometown to visit his mother, too.

Jiao's health was already poor when he arrived in Lankao. He found a Chinese medicine doctor whose prescription seemed to be working for him, but he stopped taking the medicine because he didn't want the county government to cover the couple of dozen yuan the medicine cost at a time when people were starving. When I told him to not work too hard and pay more attention to his own health, he said to me in a guilty tone, "Yanfang, we didn't do a good job. Lankao had its golden era before 1957. (We) dragged it into poverty like this. We owe it to the people here." This courageous self-criticism no longer exists in the Communist Party.

When Jiao died from liver cancer on May 14, 1964, my mother, who got her job with Jiao's help, was overwhelmed by sadness and she had to be hospitalised. I went to visit her and she told me more stories about how Jiao had devoted his life to the people of Lankao. When I went back to the film studio, I suggested making a movie about him. My boss sent me and a team to Lankao to do research, in March 1965. This was before the Xinhua profile of Jiao made him a nationwide role model in 1966. I had the freedom to approach the story without any propaganda guidance. I interviewed Jiao's family, colleagues and friends. And I was able to obtain many authentic documents. One of these documents was a report Jiao directed the Lankao government to write and file to higher-level government, which noted that the quantity of fertile land, the number of livestock and the production of crops had all slid to levels existing before the communists took over in 1949. I learned that when the report was drafted, some members of the county government didn't want to put this paragraph in. They said that happened under the previous county administration and had nothing to do with the current one. But Jiao said, "The previous administration was also part of our Communist Party." Today's Communist Party doesn't want to face history with the same candour and courage.