Tracing the roots of Hong Kong's laundry business

Whether commercial or domestic, laundries have become ubiquitous in Hong Kong, writes Jason Wordie

Commercial laundries are a staple of Hong Kong’s backstreets and remain commonplace businesses throughout the world’s Chinatowns. From New York to Kuala Lumpur, Chinese-operated laundries are an essential part of the local scene.

The contemporary local popularity of commercial laundries is partly caused by the limited space in many Hong Kong apartments.

Few kitchens or bathrooms are large enough to accommodate a washing machine and, in older buildings, inadequate water pressure often means automatic models cannot function efficiently.

Economies of scale make it cheaper for families to use a commercial laundry on a regular basis than to try to find space to dry their clothes at home. This remains particularly true for large items, such as towels, blankets and bedsheets.

Not everyone can afford to send out their washing, however; Hong Kong’s public housing estates are internationally renowned for their thousands of bamboo laundry poles, all gaily festooned with garments, dozens of storeys above street level.

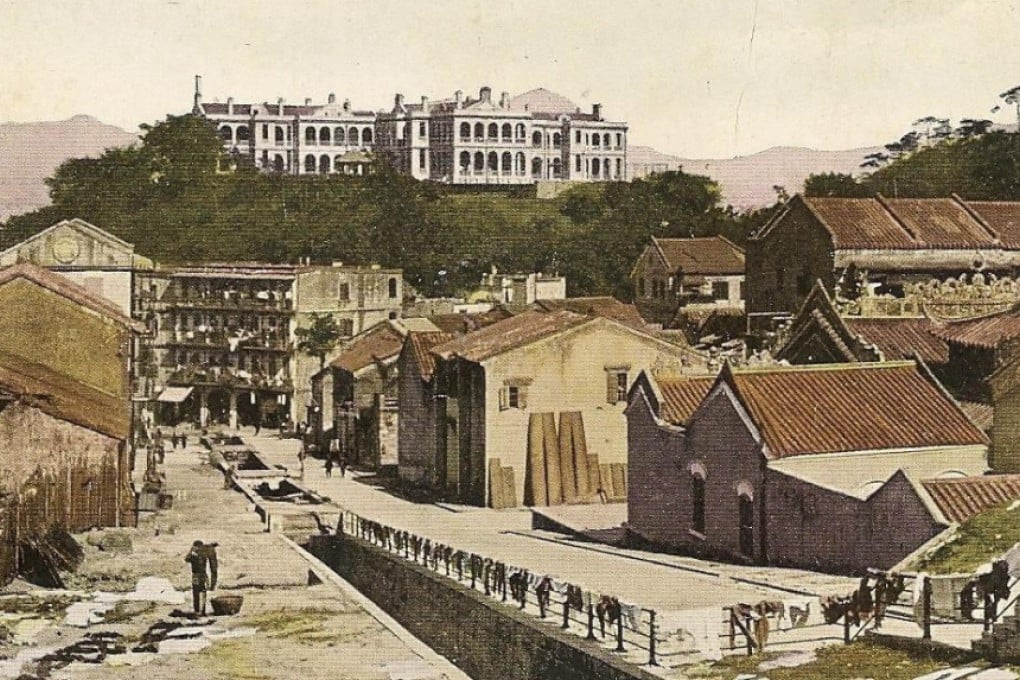

Before the widespread availability of reliable piped water transformed life across Hong Kong, commercial laundries depended on fast-flowing streams in accessible urban locations.