Then & Now | China marks Japan's Pacific war surrender with half-truths

Turning the spotlight on external grievances – especially historical enemies – neatly distracts from current domestic political and economic problems, writes Jason Wordie

War anniversaries, and their emotional significance, extend far beyond the specific calendar dates of battles, victories and defeats.

Like national independence days, contemporary (and periodic misuse of) war commemorations help us to understand political utilisation of historical facts for present-day purposes.

The rearranging of commemorative dates connected to the end of the Pacific war in Hong Kong to suit broader political agendas is a prime example.

China was terribly mauled by the Japanese following the latter’s invasion in 1937; a reasonable view maintains that the Pacific war actually started in earnest then, rather than with the coordinated Japanese attacks on the Western powers in Hong Kong, Malaya, Singapore, the Philippines and Hawaii on December 7 and 8, 1941.

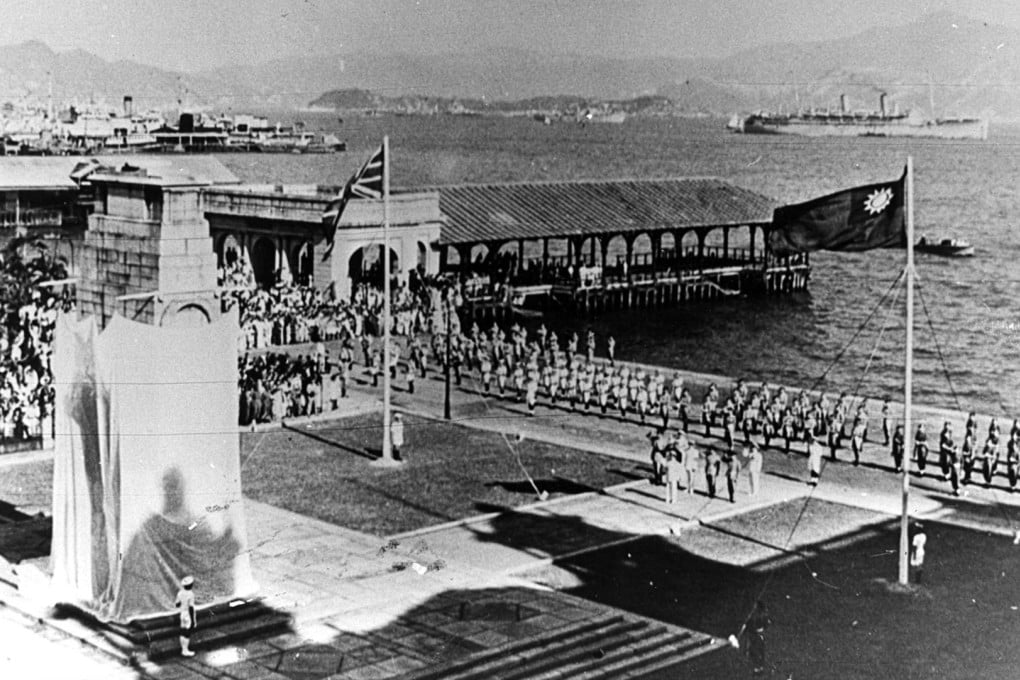

On August 30, 1945 – 70 years ago today – Hong Kong was officially liberated from the Japanese by British forces.