Then & Now | Barren rock: Hong Kong’s hillsides weren’t always so lush and green

It’s hard to believe that Hong Kong, with its lush hillsides, was once a jumble of barren rocks, writes Jason Wordie

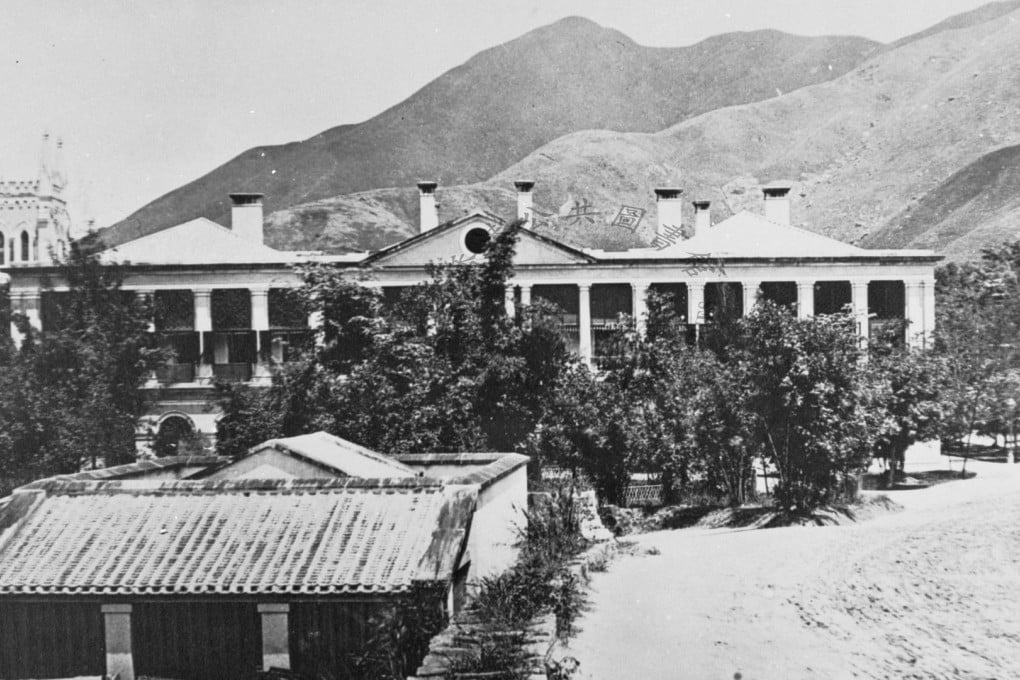

Photographic evidence from the mid-19th century until well into the 1950s amply demonstrates that Hong Kong’s hillsides were mostly badly eroded and bare of vegetation. From this visual evidence, and numerous descriptions left behind in period memoirs and travel accounts, one can see where the early “barren rock” description originated. But how did Hong Kong’s mountainsides become so denuded?

Extensive deforestation around the eastern side of the Pearl River estuary accelerated from the mid- 19th century. Long grasses took the place of trees stripped away for firewood and not replanted, and by the 1820s, the mostly granite islands around the eastern side of the delta, including Hong Kong, were barren rocks. And as cordwood became depleted, coarse grass itself was gathered as a supplementary fuel.

The main grass harvested was thick, heavy-stemmed Imperata cylindrica, commonly known as cogon grass. Known in the Malayspeaking world as “lalang” and in Australia as “blady grass”, the name is painfully appropriate as the leaves have sharp edges and slash into exposed skin easily. To prevent being badly scratched, grass-cutters wore woven split bamboo or rattan gauntlets on their arms. Examples can be seen in local ethnographic museums, such as Sam Tung Uk, in Tsuen Wan.

Once gathered, grass stems were twisted and knotted into thick “sticks”, which were then sun-dried and used for cooking fuel. Faster burning than other solid fuels, such as wood or charcoal, grass sticks were nevertheless better than nothing, and best of all, grass could be gathered for free. That cogon tends to burn quickly – even when apparently green – partly accounts for the rapid spread of hill fires in those parts of Hong Kong where this grass is most prevalent.