Update | Why Hong Kong has Mao to thank for ID cards

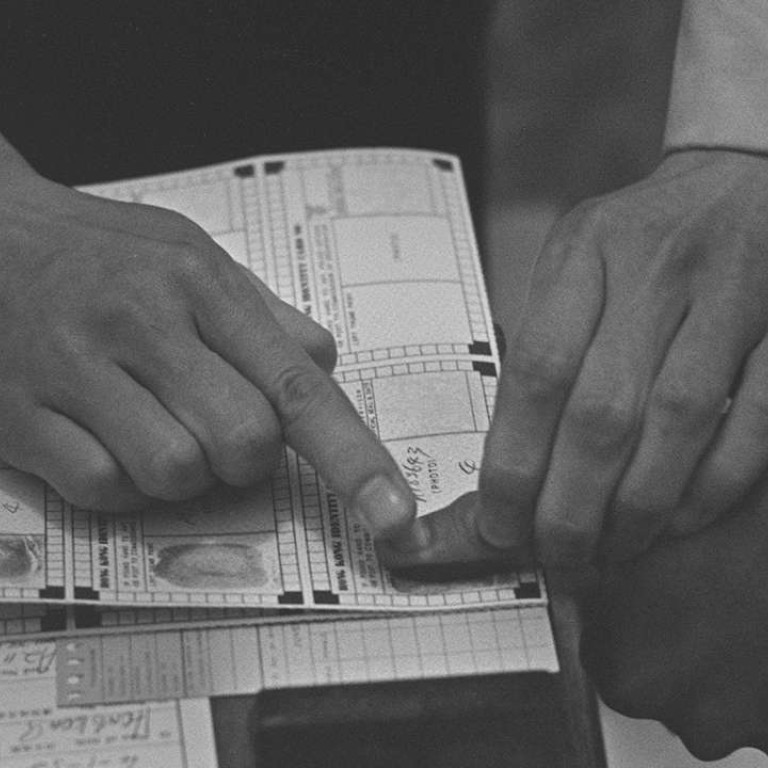

British colonial administration, braced for chaos and a tide of refugees from Communist takeover in China, began registering population and issuing them identity cards in the summer of 1949

In 1949, the British colony was preparing for chaos and an influx of refugees, as civil war raged in China. On October 1, Mao established the People’s Republic of China.

Attorney general J.B. Griffin moved earlier that summer for Hong Kong to register all persons in the colony and issue them identity cards. By September, it was announced the government would register 5,000 people per day, a task that would take years.

“It is quite normal customarily to use more than one name in everyday life in Hong Kong and second there is the difficulty of romanisations,” said D.C. Trench, acting colonial secretary.

Consequently, a Chinese adult would be asked to choose their official name, and use it thereafter in all dealings with the government. It wasn’t until 1973, however, that the identity card could properly record Chinese names; a headline in the Post on May 10 that year announced: “ID cards will be bilingual.”

Chinese names had also given rise to another problem: that of identity swapping.

“The Chinese, unlike Western societies, have a large number of given names but a limited number of family names,” the Post stated. Dr S.Y. Chung told the newspaper, “Chan, Lee, Cheung, Wong, Ho, Au, Chow, Wu, Ma and Mak represent more than half of the population in Hong Kong.”

Consequently, ID cards were passed around by young people so those under the working age of 14 could gain employment.

In 1983, the Post introduced readers to the “new look” ID card, which was harder to forge, smaller, designed by the Bank of England and logged on a computer system.

On May 2, 1983, the first day of applications, Hongkongers queued from 4am for their new ID card. While the poster advertising them featured two men grinning, applicants had been warned in advance: no smiling during photo-taking, please.