Then & Now | One country, many cisterns: when Hong Kong’s Toilet King grew rich

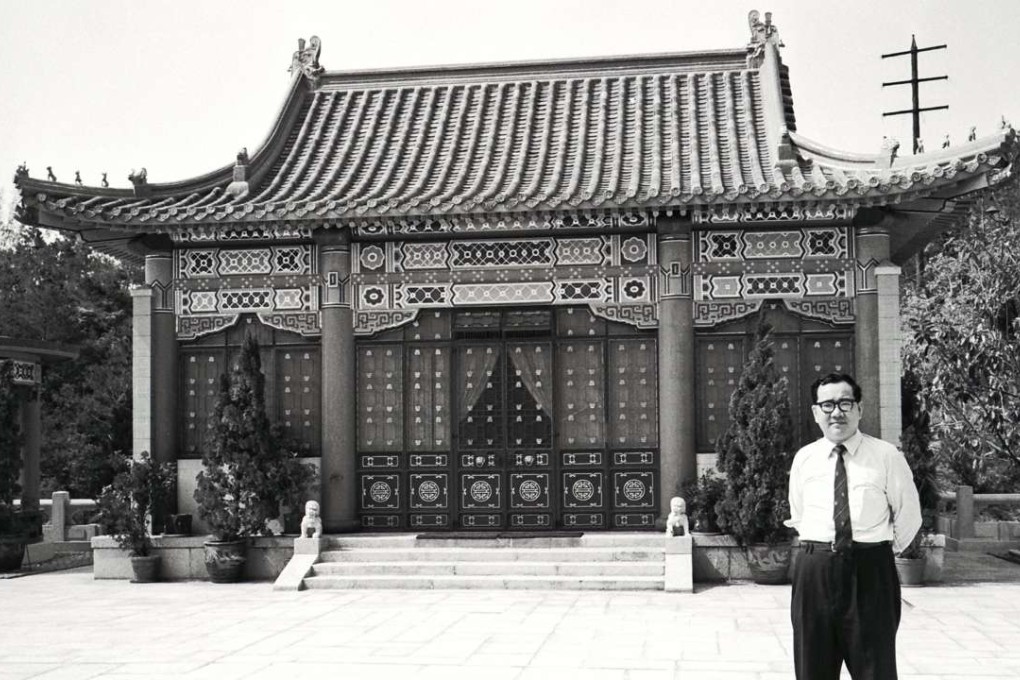

Engineer Lee Iu-cheung made a fortune selling locally made sanitaryware during Hong Kong’s post-war boom, but in the ‘barren rock’s’ earlier years most construction material had to be imported

Hong Kong’s demolition, construction and renovation industries have long been economic staples. Likewise, sourcing the materials that have made these profitable industries possible remains of parallel economic importance.

Quarrying and stone cutting were Hong Kong’s earliest construction-material industries, with a lengthy pre-European-era history. But with few indigenous natural resources, many of the other materials and tools needed for building had to be imported.

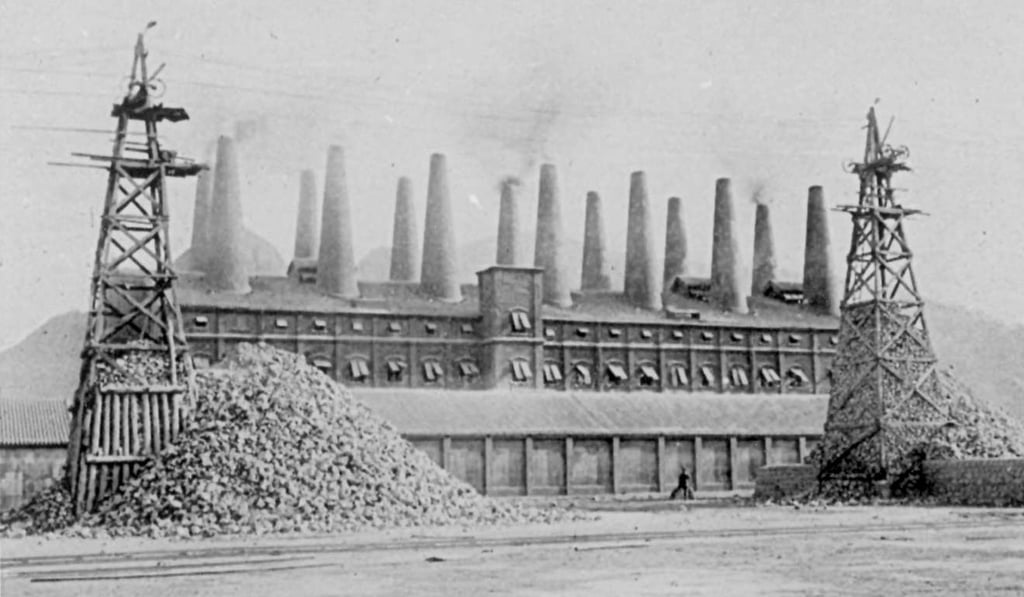

Concrete was manufactured locally from 1887, when Green Island Cement was established in Macau. Later purchased by Hong Kong interests, the factory was relocated to Hung Hom, where cement kilns remained a major employer – and source of pollution – for several decades.

Chinese-style roofs – near universal across Hong Kong until after the Pacific war – usually survived seasonal typhoons, and locally produced, inexpensive encaustic cement roof tiles were readily obtainable when repairs were needed.

From the 19th century to the present day, much of Hong Kong’s building timber, from sawn planks and veneers to the cheap plywood and high-density particle board popular in local furniture manufacture, has been sourced from Southeast Asia. For several decades, most of this came from North Borneo (modern Sabah); the British North Borneo Company, which ruled there from 1881 until 1946, when the territory became a British colony, was partially founded by Hong Kong commercial interests.

Sandakan was established as a timber port, and Chinese migration from Hong Kong – mostly Hakka Christian converts from Shau Kei Wan and Sai Ying Pun – was partially assisted by Lutheran groups. With close business and family links, Sandakan eventually became known as “Little Hong Kong”.