How ‘kowtowing’ acquired a negative connotation in English

The practice dates back to the Qin dynasty, when subjects prostrated in front of the emperor as an act of respect, but it was only after foreigners visiting China found the practice disdainful that the word came to mean ‘submissive’

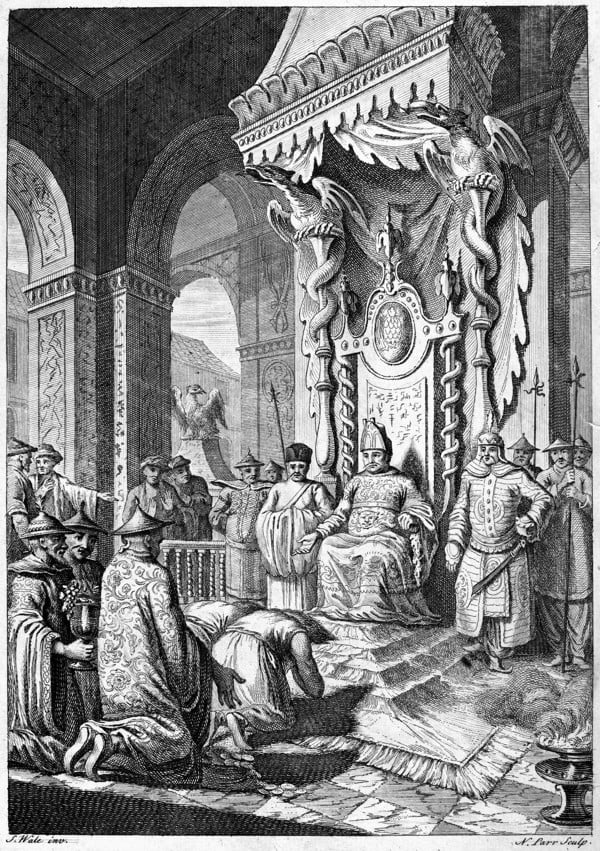

British explorer-author Sir John Barrow noted in his book Travels in China (1804) the Chinese custom of touching the ground with the forehead in the act of prostrating oneself, as an expression of deep respect, submission or worship, describing this as “koo-too, or ceremony of genuflexion and prostration”. Also found as ko-tou or ko-tow in other travellers’ writings, this has been standardised as kowtow or kow-tow, from the Chinese 叩頭 (Cantonese kautàu, Putonghua kòutóu), meaning “knock head”.

From kowtow comes finger kowtow (or tea tapping). This is the light tapping of one’s bent index and middle (and sometimes ring) fingers on the table thrice after one’s cup is filled, in thanks to the tea server. The custom purportedly originated in the Qing dynasty, when the emperor, travelling incognito throughout his empire, might fill his servant’s teacup; the servant, so as not to reveal the emperor’s identity, would perform a finger kowtow in lieu of prostration.

In many East Asian cultures kowtowing, or its equivalent – Japanese bowing, Southeast Asian wai – is a serious, respectful practice. However, the act was regarded with disdain by foreigners visiting China: European emissaries in the late 18th and the 19th centuries often refused to kowtow to the emperor. Unsurprisingly, the word acquired a negative connotation in English.

In contemporary usage, “kowtow” has shifted to a figurative meaning of acting in a submissive, obsequious manner. This has seen a spike in usage in the past three years in the context of Hong Kong, with reference to the apparent obsequious obeisance to Beijing’s wishes of various nations and companies, to the detriment of the SAR’s rights. Twenty years after the handover, Hongkongers will likely appreciate the plurality of these interpretations.