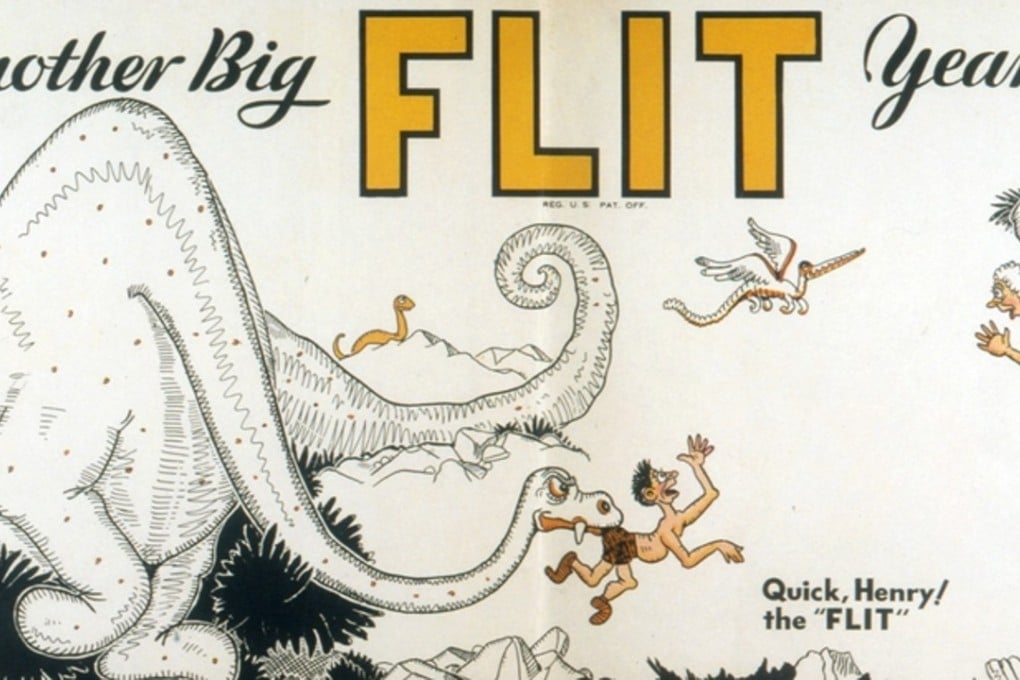

Then & Now | How Hong Kong kept mosquitoes at bay – remember Flit?

Nets, coils, insecticides and Indian tonic water were all developed to deal with malaria

Debilitating fevers, such as dengue and malaria, were until recently part of everyday life across Asia. For hundreds of years, certain areas were simply deemed “unhealthy”; exposure to “the night air” and other toxic miasmas believed to emanate from the ground, rocks or the atmosphere in certain seasons, were regarded as the culprits.

Early European accounts of the Canton Delta all mention its pestilential climate and the prevalence of fatal fevers. Hong Kong even had its own variety, described in travel accounts as “Hong Kong Fever”; whether this was actually malaria or dengue is not documented.

In the first few years of British rule on Hong Kong Island, the Wong Nai Chung plain, with its poorly drained former paddy fields, was notorious for fever. Happy Valley, the English name for the area, was taken from mordant British Army humour; the place you went when you were dead.

Malaria genome shows a cunning, finely tuned parasite, says study

After decades of scientific speculation, malaria’s mosquito-borne origins were conclusively proven in Calcutta in 1898 by microbiologist Sir Ronald Ross, who was later awarded the Nobel Prize for Medicine for this discovery. Connections between mosquito bites, blood contamination and disease progression were now in no doubt, but as a cure remained elusive, effective prevention was essential.