How cotton once rivalled opium in importance for Hong Kong – and helped build city’s textile trade

Hong Kong’s success as a garment hub can be traced to the American and Chinese civil wars – as well as to a humble Indian bottle seller

Opium remains the most widely remembered commodity traded by the British East India Company between India and China. During the 18th and 19th centuries, however, another product assumed nearly the same economic importance – cotton.

Finished cotton products had been traded from ports in western India and into Southeast Asia and China for hundreds of years before the arrival of Portuguese navigators in the early 16th century.

By the mid-19th century, one of the region’s principal cotton brokers was Parsee businessman Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy, who had started out trading in glass bottles (he was popularly known as Bottle-wallah for this reason). From that humble beginning, Jeejeebhoy went on to grow a multilayered business empire (opium, admittedly, did play a role) that stretched from India to China, becoming a major philanthropist in his home city of Bombay, where numerous public institutions, such as schools and hospitals, still have “Sir J.J.” as part of their name.

One such institution, Sir J.J. School of Art, employed as its principal the British sculptor and ceramicist John Lockwood Kipling, father of the poet, writer and Nobel laureate Rudyard Kipling.

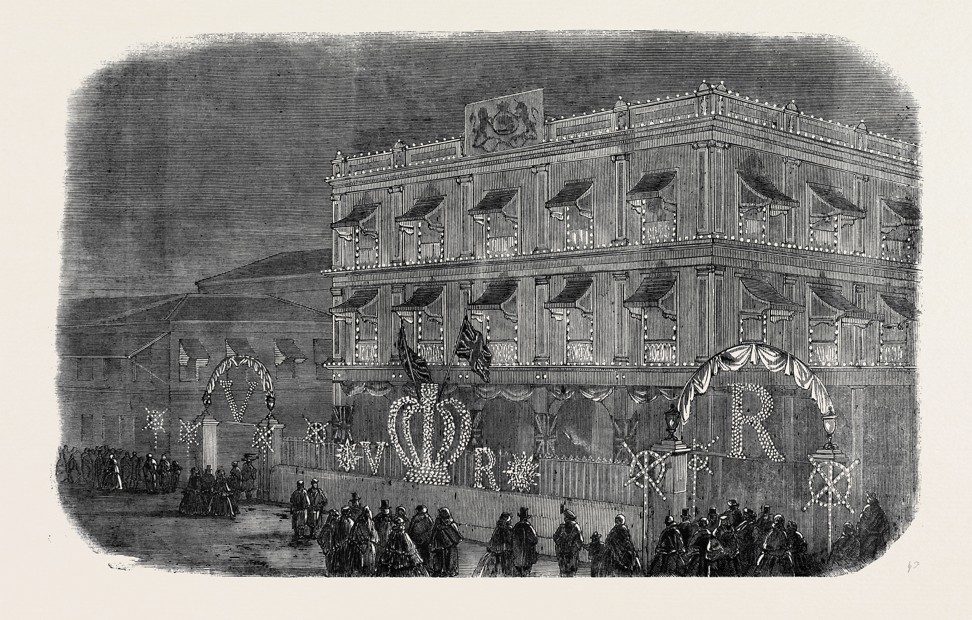

Knighted in 1842, Jeejeebhoy was subsequently raised to the British peerage in 1858, as Baron Jeejeebhoy of Bombay. The title remains extant; his direct descendant, the 8th Baron Jeejeebhoy of Bombay, still makes his home in India.

Hong Kong’s early cotton industry was part of an attempt to redress a massive global shortfall caused by the American civil war (1861-65). During these years, cotton exports plummeted. Production in the conflict-ravaged southern states only returned to pre-war capacity in the late 1870s.

In the 1860s, cotton imported mostly from India was processed into yarn at a Jardine Matheson-owned mill in Causeway Bay, where St Paul’s Hospital and St Paul’s Convent School now stand. Cotton Path, just behind the complex, recalls the local industry.

Meanwhile, cotton growing – and associated ginning and spinning enterprises – was attempted in places as unlikely as Fiji and Mauritius. And production was massively expanded in places with historically significant cotton industries, such as India, Egypt and the Sudan. Cotton growing also started in Australia at about this time.

In the late 1940s, as the Chinese civil war intensified, Hong Kong’s then-small textile industry received a massive boost with the arrival of fleeing capitalists from the lower Yangtze region. Abundant refugee labour, willing to work for almost any wage, enabled the industry to rapidly expand.

Preferential tariff agreements between Hong Kong and Britain in the late 50s helped the industry to move up the value chain, from maker of cheap cloth to manufactured garments.

Hong Kong’s three-decade period as one of the world’s leading textile manufacture and export centres also spawned a generation of “rentier” families, who farmed out the quotas the government awarded them. An unintended consequence of this policy was the inadvertent creation of another property-baron class. Industrial holdings in places such as Kowloon Bay, Kwun Tong and Tsuen Wan created a massive land bank for future use, which is only now being fully realised as decaying former factory buildings are redeveloped into commercial-industrial complexes.