Then & Now | Two Chinese ‘uncle’ stereotypes that smugly superior Hong Kong once sneered at

Discernible by their language and dress, Southeast Asian-born and Californian expatriate Chinese ‘uncles’ were often the butt of jokes

Until recent years, a subset within Hong Kong’s ethnic matrix were Southeast Asian-born overseas Chinese, who ended up living, sometimes unwillingly, in Hong Kong. In many cases they looked and behaved much the same as everyone else, so what were the telltale clues that differentiated them from the majority?

Many were darker-complexioned and more round-eyed than the average southern Chinese. Starting in the mid-19th century, Chinese sojourners to the Nam Yeung (“South Seas”) usually set out as single males, who decamped in their thousands from impoverished ancestral villages to make their fortunes in tropical lands.

This initial generation intermarried (or cohabited), which meant Malay, Javanese or Siamese features eventually merged into the Chinese racial melting pot. Children were raised to think of themselves as Chinese – their father was, after all – but in terms of food, language, dress and sanitary habits, their home culture increasingly became Southeast Asian.

Language was an immediate giveaway. Over the generations, Cantonese speakers in Malaya absorbed local words into their language. Pa-sat, a Cantonese approximation for the Malay pasar (“market”), and pan-nai, from pandai (“to understand”), are common examples. Such words became widespread across Southeast Asia among Chinese speakers.

These loaned phrases, however, were unknown in this city and, in the arrogant Hong Kong Chinese way, the “barbaric” terms were usually sneered at.

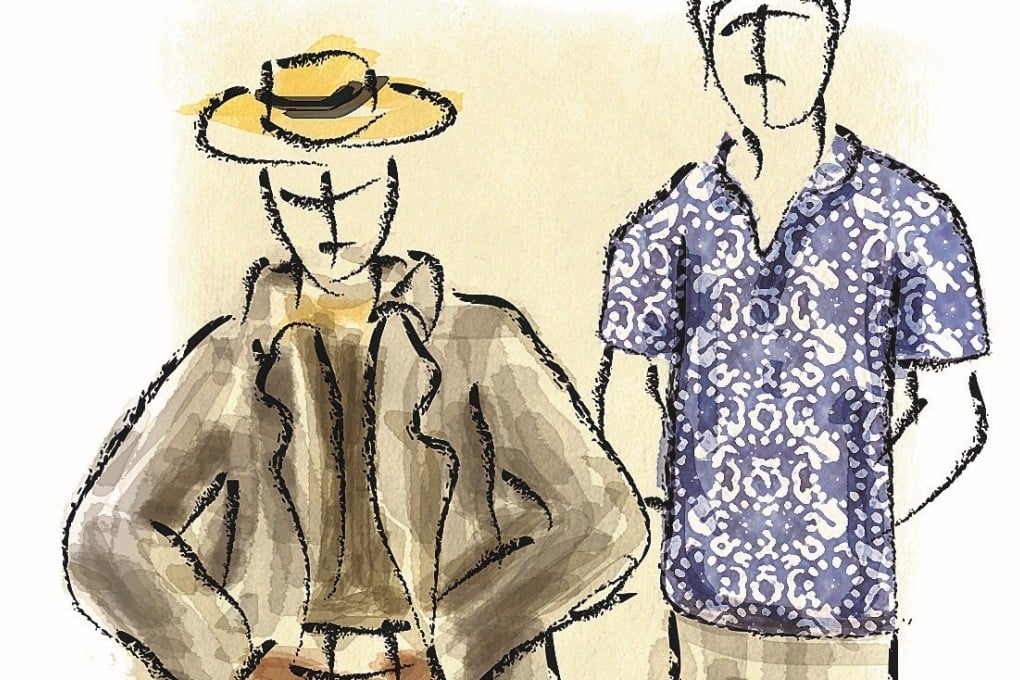

Post-war films, especially Hong Kong-made movies with an anticipated regional distribution, featured the batik-shirt wearing, fractured-Cantonese-speaking Nam Yeung Ah Bat as a stock comic character

In consequence, Nam Yeung migrants in Hong Kong adapted their language, only reverting to earlier dialects when among friends from similar backgrounds. Others – more defiantly individual than is usual in Hong Kong – continued to deploy such words as a statement of personal identity.