Thomas Coryat, the world’s first backpacker, travelled from Britain to Asia on foot – for fun

- His name may have fallen out of historical favour but the eccentric Englishman was a pioneer of budget travel

- He walked to India at a time when few people would have dreamt of venturing further than their front door for pleasure

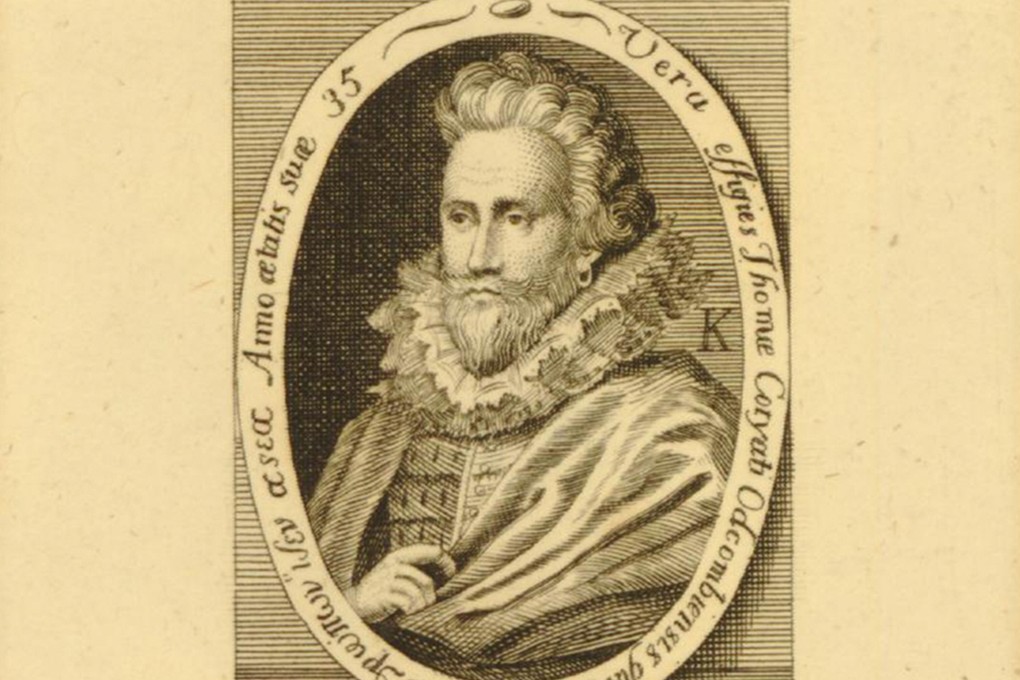

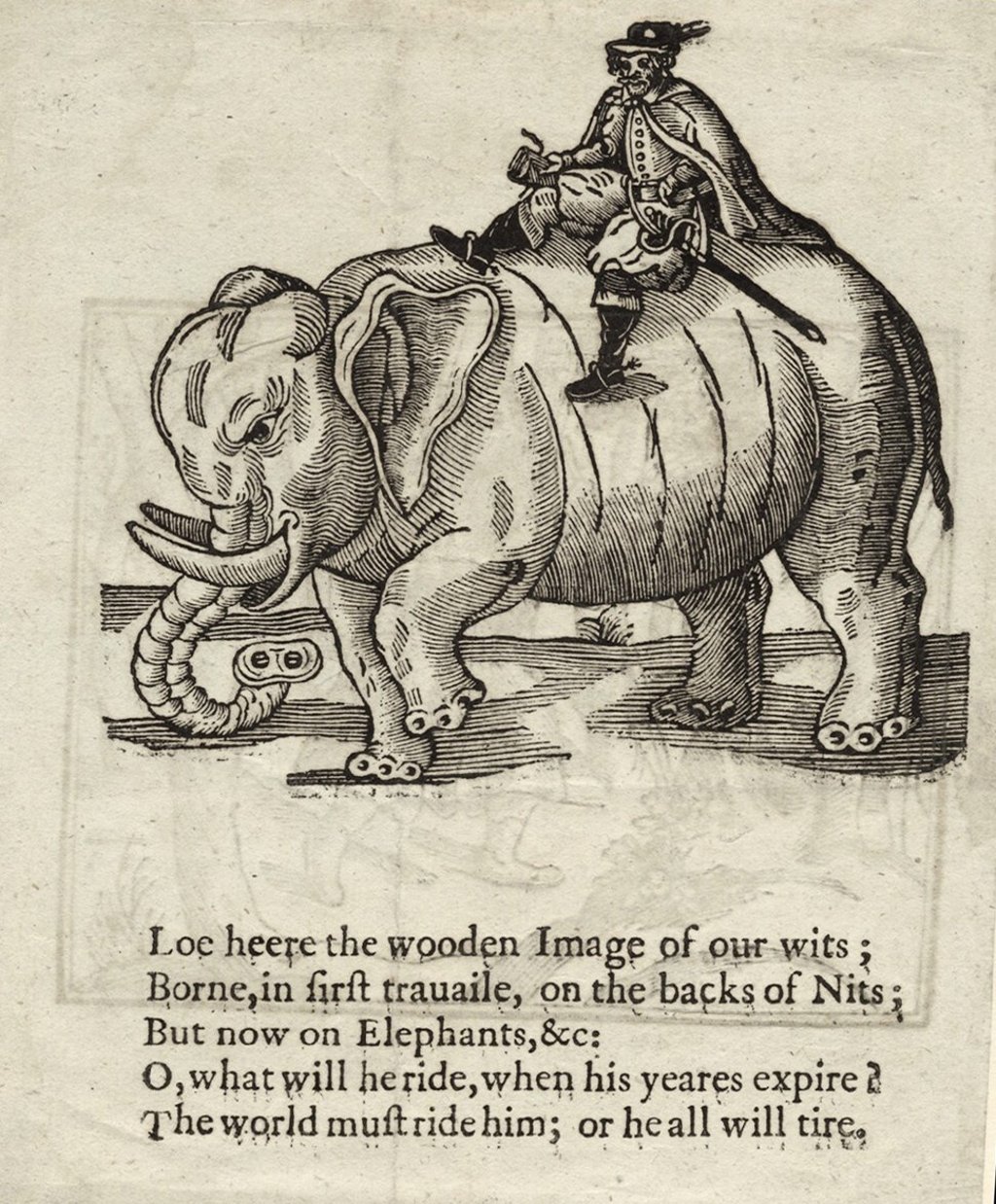

Thomas Coryat was the original backpacker, a globetrotter when there was still some doubt that the world was round, the fledgling tourist. In the early years of the 17th century – a time when people were reluctant to venture beyond their front doors if they could help it – he walked from Europe to India. What’s more, Coryat did it for fun. And he wrote about it, so he might even be called the first blogger.

Way in advance of tour operators’ copywriters and unwittingly laying the path for generations of holidaymakers to come, he declared: “Of all the pleasures in the world travell is the sweetest and most delightfull.”

The son of an English country parson, Coryat – whose name is sometimes spelled “Coryate” – had two great gifts: he was a talented linguist and he was fired by an insatiable curiosity about everyone and everything around him. His first overseas jaunt took him to Europe in 1608. Whether it was a giant clock in Strasbourg or a high-class courtesan in Venice, he wanted to find out as much as he could about what made them tick.

When there was no room at the inn, he would doss down in a stable. He had to dodge the Spanish Inquisition in Bergamo (its officers would have been suspicious of a Protestant wandering about for no comprehensible purpose) and flee from an irate German farmer after absent-mindedly helping himself to the man’s grapes. It all made for a racy narrative.

Coryat was sometimes held up by floods, and – foreshadowing travel restrictions in 2020 – occasionally obliged to submit to health inspections before he could proceed. Finding the way – there were few reliable maps and fewer road signs, none of which were multilingual – was a constant problem.

“Travel in the 17th century was a communal affair,” says Matthew Edney, Osher Professor in the History of Cartography at the University of Southern Maine (USM) in Portland, in the United States, which mounted an exhibition in 2011 to commemorate Coryat’s achievements.