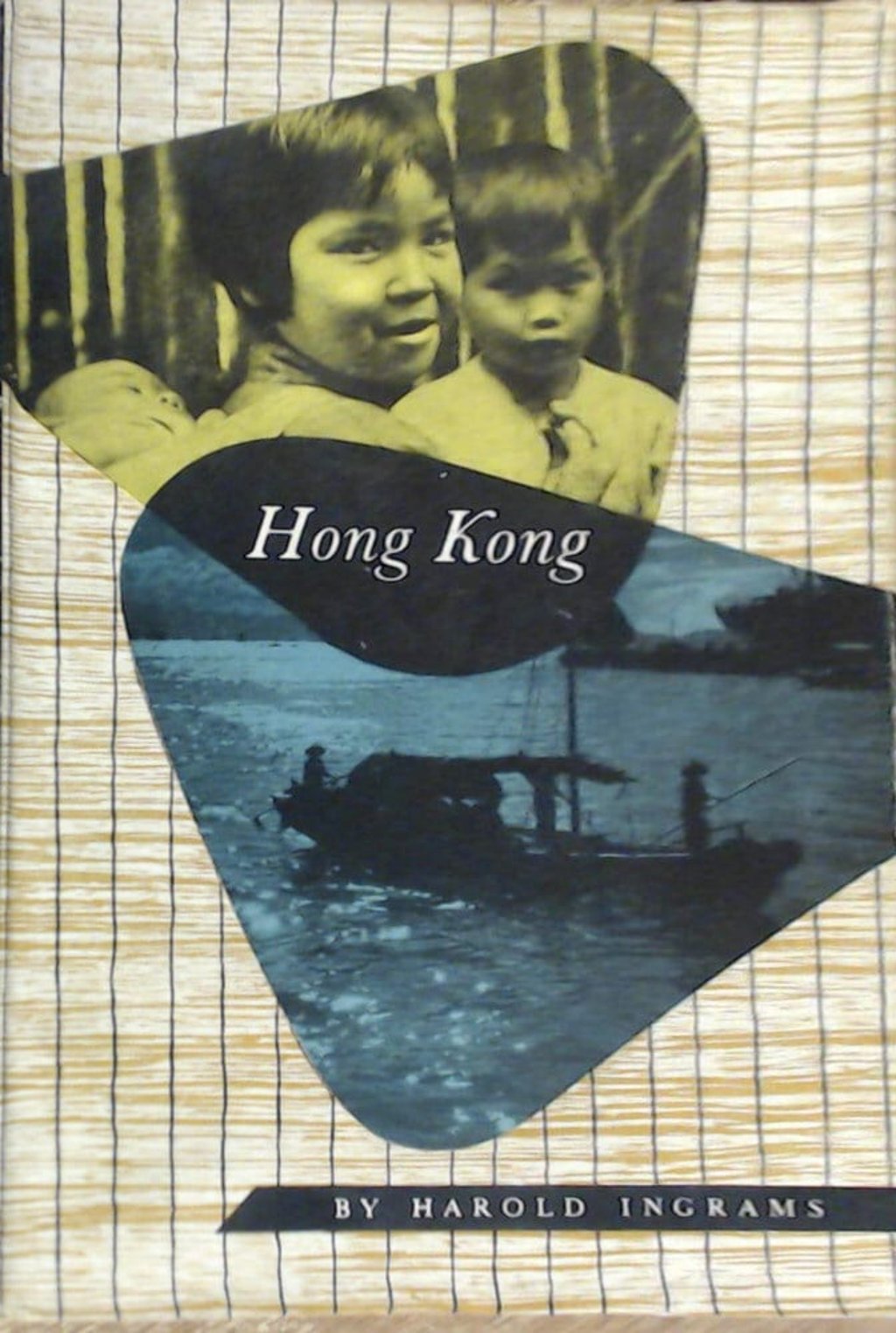

Then & Now | Colonial administrator’s sympathetic view of 1950s Hong Kong in Corona Series of far-flung corners of the British Empire

- Retired administrator and author of the series’ Hong Kong volume, Harold Ingrams combined readability and flashes of wit with factual information

- His sympathy and understanding for the territory’s peoples gave colour to what in other hands might have been an anodyne record of time and place

Linked to the Colonial Development and Welfare Scheme, which extensively subsidised primary production, from forestry to fisheries, the Corona Series produced detailed survey volumes about overseas territories. These combined a travel writer’s eye for local colour and telling detail with solid factual information. All were written when many colonial territories still seemed a few decades away – at least – from political independence.

Given the assumption that a steady stream of British administrators and businesspeople would likely arrive for the foreseeable future, it made sense to ensure new residents were well informed about the places where they could expect to spend large tracts of their lives. And with cross-postings between territories common, being able to familiarise oneself before arrival would be invaluable. Almost as the Corona Series got fully under way, however, rapid decolonisation occurred, and the final books covered the last colonial territories to gain independence – mainly in the Pacific.

The first volume was Hong Kong (1952), written by recently retired British administrator Harold Ingrams (1897-1973), who spent much of his service career in the Aden Protectorate (now part of Yemen). Ingrams had a well-deserved pre-war reputation across the Arab world – along with his formidable wife, Doreen, later a successful broadcaster – for brokering a lasting ceasefire among feuding Arab tribes, known as “The Ingrams Peace”.

Fluent Arab speakers with a dislike for pomposity and racial prejudice, the couple made lasting friendships across ethnic and social distinctions; for decades afterwards, parents in Aden admonished squabbling children with the warning that “they’d tell Mrs Ingrams!” Apparently, this dire threat brought about instant domestic peace – as it had done earlier, to more threatening tribes.