Denied an education in the name of ‘free market’ economy, the elderly, semi-literate Hong Kong cleaners and sweepers betrayed by its earlier administration

- Neo-liberals venerate former Hong Kong financial secretary John Cowperthwaite, with his non-intervention creed, as the architect of city’s post-war ‘miracle’

- Yet his opposition to compulsory free education left the children of poor families semi-literate at best, condemning them to menial service jobs in later life

Ever wondered why Hong Kong’s public toilets, wet markets and swimming pools have an oversupply of underemployed cleaning staff? Walk around public parks, and someone, somewhere, will be sweeping leaves and twigs while a second person holds the dustpan, a third bags up the haul, and yet another takes it all away.

Even by (admittedly unexacting) Hong Kong government time-and-motion efficiency standards, or just common sense, these examples represent a mind-blowing waste of public resources. Or do they? After all, these occupations provide a bare living to people who would otherwise be unemployable.

But why are they otherwise unemployable? Until 1971, there was no free, compulsory primary education in Hong Kong; universal secondary education (up to Form One – grade seven) was only introduced in 1978. This shocking deficit directly created an entire post-war generation who grew up semi-literate.

If poor families needed extra income, younger people went out to work, at whatever they could find; it was basic economic survival. In the days when factory jobs were abundant, working a “jumping jack” resin extrusion machine to make plastic doll heads and artificial flowers, or operating spinning jennies, power looms or sewing machines, required physical stamina combined with practical skills acquired on the job – but not functional literacy. Basic numeracy came through everyday life; watching Granny do her daily market shopping taught most children the essentials.

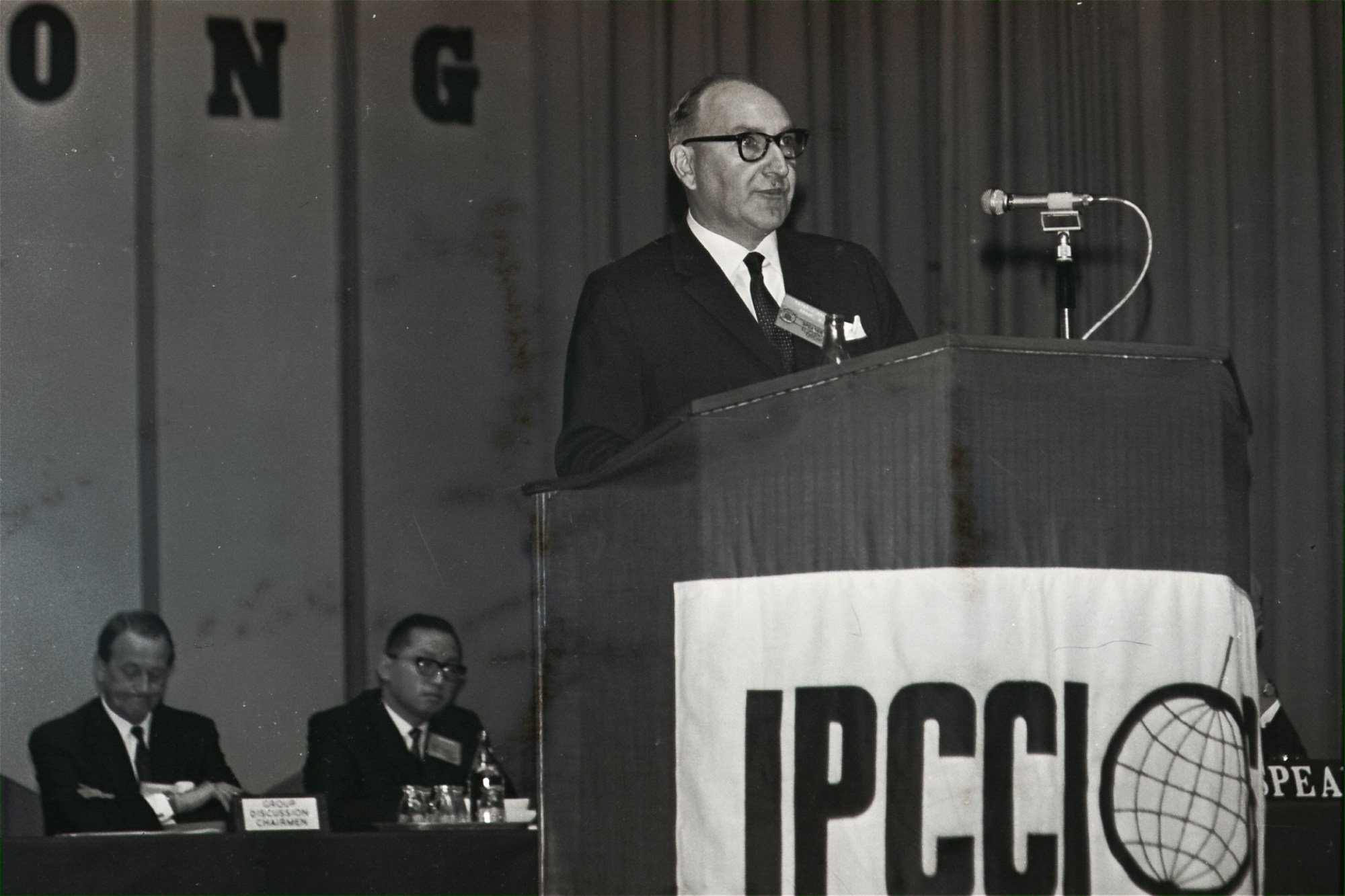

Moves towards universal education in Hong Kong were adamantly resisted throughout the 1960s by the then financial secretary, John Cowperthwaite, a devotee of Ayn Rand – any reader of her grotesquely overrated economic philosophy/novels The Fountainhead (1943) and Atlas Shrugged (1957) should see where this leads.

Anything that could be done to minimise and obstruct government spending for the benefit of the population for whom they were responsible, in favour of “the free market”, was done. Cowperthwaite also opposed two other projects of great civic benefit; the Cross-Harbour Tunnel, and the MTR. Neo-liberals – few of whom have experienced poverty first-hand – still venerate the man as the architect of Hong Kong’s post-war “miracle”.

About 20 years ago, while working on a research project, I spent an afternoon with Cowperthwaite, at his home in St Andrews, Scotland. Arrogant and condescending (his sour wife was an equal match), this experience permanently discoloured my opinion.

Forewarned by his former colleagues to expect some display of studied rudeness, I was not disappointed. At 4pm, in the midst of our discussions, a single cup of tea and one biscuit appeared; my water bottle sufficed, by way of refreshment – it had to.

Petty though this recollection might appear, Cowperthwaite’s smug, overprivileged face materialises in my mind’s eye when, somewhere around Hong Kong, I chance upon someone – of about the right age – toiling away in some menial, endlessly repetitive occupation. That unfortunate person’s entire life experiences were in all likelihood thwarted before they even had a chance to begin, by the short-sighted, ethically bankrupt, “I’m fine – stuff you!” socio-economic policies Cowperthwaite and his fellow “neo-liberals” espoused.

Hong Kong a free economy? Don’t make me laugh

Of course, the ultimate “cost-saving” fallacy for these theories can be seen today; the modern-day Hong Kong government pays far more to subsidise legions of more-or-less unnecessary jobs for working-age semi-literates than it would have originally done to educate and help advance the younger versions of these people.

And how many working-class children would subsequently have gone on, with legendary Chinese drive and determination, and a timely leg up along the way, to contribute far more to society than they were ever able to do? We will never know.