What is one’s ‘first language’ in Hong Kong when Cantonese, English and others can meld together in the mind?

- One day I spent in a Portuguese household 25 years ago opened a window to a multilingual world that is fast disappearing

- For some, being brought up from infancy around a number of languages makes them simultaneously at home in each and none of them

Personal circumstances dictate what one speaks as a first language. But what happens when several are used at the same time, which also means that no single one predominates, either in spoken or written form, and thus they congeal into a primary “language of the mind”?

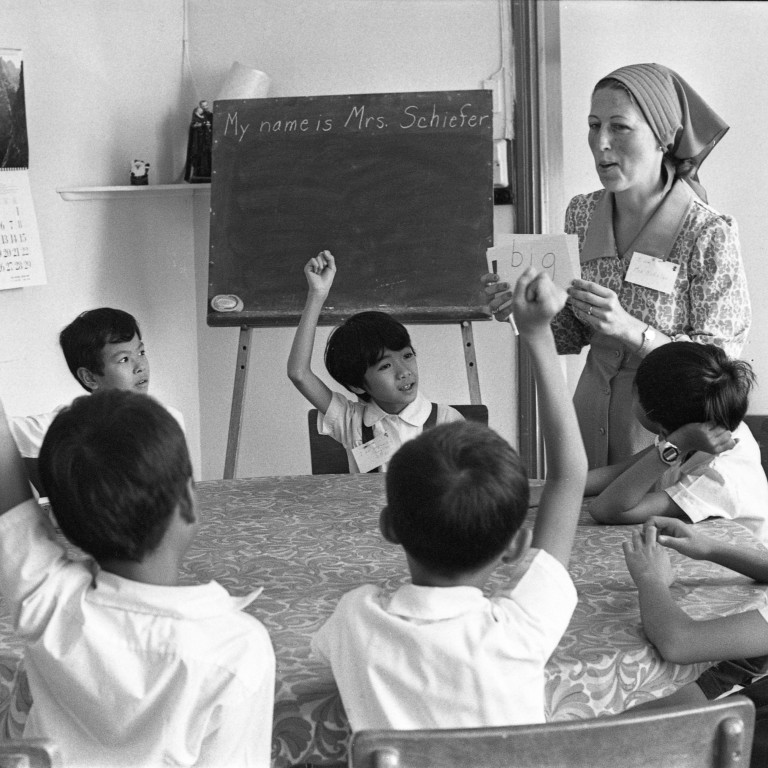

For some local people – of whatever ethnic origin – mixed code teaching in what were considered the more superior Hong Kong schools, and being forced to learn in a foreign language – English – to which most students had little everyday exposure, had that effect.

Some excelled in the language of the classroom – in the Hong Kong way, where outward form is generally mistaken for underlying substance – and oral fluency created the misleading impression that rather more occurred between their ears than might have been the case.

Others gave up in anger and despair, and the potential for pathways into other worlds that different languages, and the diverse ways of thought that they reveal, might have brought, was wasted. A lifelong sense of cultural inferiority – which could be manifested in all manner of sad and destructive ways – too frequently was the result, and permanently blighted their lives.

‘Historical nihilists’ know that the truth ultimately seeps through

For a few, being brought up from infancy around a number of languages made them simultaneously at home in each and none of them. A fascinating morning, more than 25 years ago, spent discussing aspects of Hong Kong life during the Japanese occupation with a prominent local Portuguese couple, offered an illustrative example.

Our conversation continued over a delicious minchee-fan lunch, after which my hostess made her excuses, and left me behind with her husband to wind up our talk. Soon afterwards, three elderly local Portuguese ladies appeared in the sitting room with her; this was their regular afternoon for ba-fa, and it was her turn to host their gathering.

Ba-fa, as further inquiry revealed, is a form of card game best described as a cross between mahjong and dominoes, but played with small paper slips. Like everything else adopted over the centuries from other Asian societies among whom the local Portuguese lived, this originally Chinese game had evolved to their own Macau rules.

Immediately intrigued – as I then was by anything to do with this creolised local culture, whether food, language, pastimes or other traditions – I asked if I might watch them play for a while. A few quizzical glances were swiftly followed by a muttered reassurance from their hostess (in rapid Cantonese, on the understandable – if mistaken – assumption that this would not be understood) “don’t worry; he’s just interested in our ways – and harmless enough!”

Who was the ‘Grand Old Man of Hong Kong’ and how did he make his fortune?

As the game progressed, and the old ladies quickly got to the underlying purpose of their card afternoon – a really good gossip session – everything else (including the person quietly observing them) was completely forgotten.

Over round after round, rapid chatter and periodic bursts of laughter swirled around the table. These ladies – all over 80, and locally educated in long-ago convent schools – seamlessly oscillated across three very different languages, and usually mid-sentence; clipped Hong Kong-accented English, crescendos of Macanese patuá, and periodic Cantonese siren-blasts ebbed and flowed interchangeably.

It was like nothing I had ever seen (much less heard) before, and briefly opened a window onto another world altogether.

They only remembered someone was watching quietly when tea time came; asked if I’d stay, I thanked them for letting me watch, and headed off. None the wiser about the finer points of ba-fa, this experience nevertheless imparted other questions about this fast-vanishing Hong Kong community.

How Hong Kong’s unattached British servicemen found love between the wars

Did these people ever think in one tongue, in primacy over the others? Or were they equally at home in all of them? Or were all these languages essentially functional or situational in usage? Distinctions never became clear and now, sadly, it is too late to ask any of them.