Profile | Why ex-Lonely Planet publisher switched to counselling: Simon Westcott on death, and being abused by a teacher

- When Simon Westcott’s best friend and parents died, he thought about the ‘huge benefit from therapy’ he had had and decided to switch careers

- He tells Fionnuala McHugh about learning he was adopted and tracing his birth parents, being abused at school and a life spent travelling and in publishing

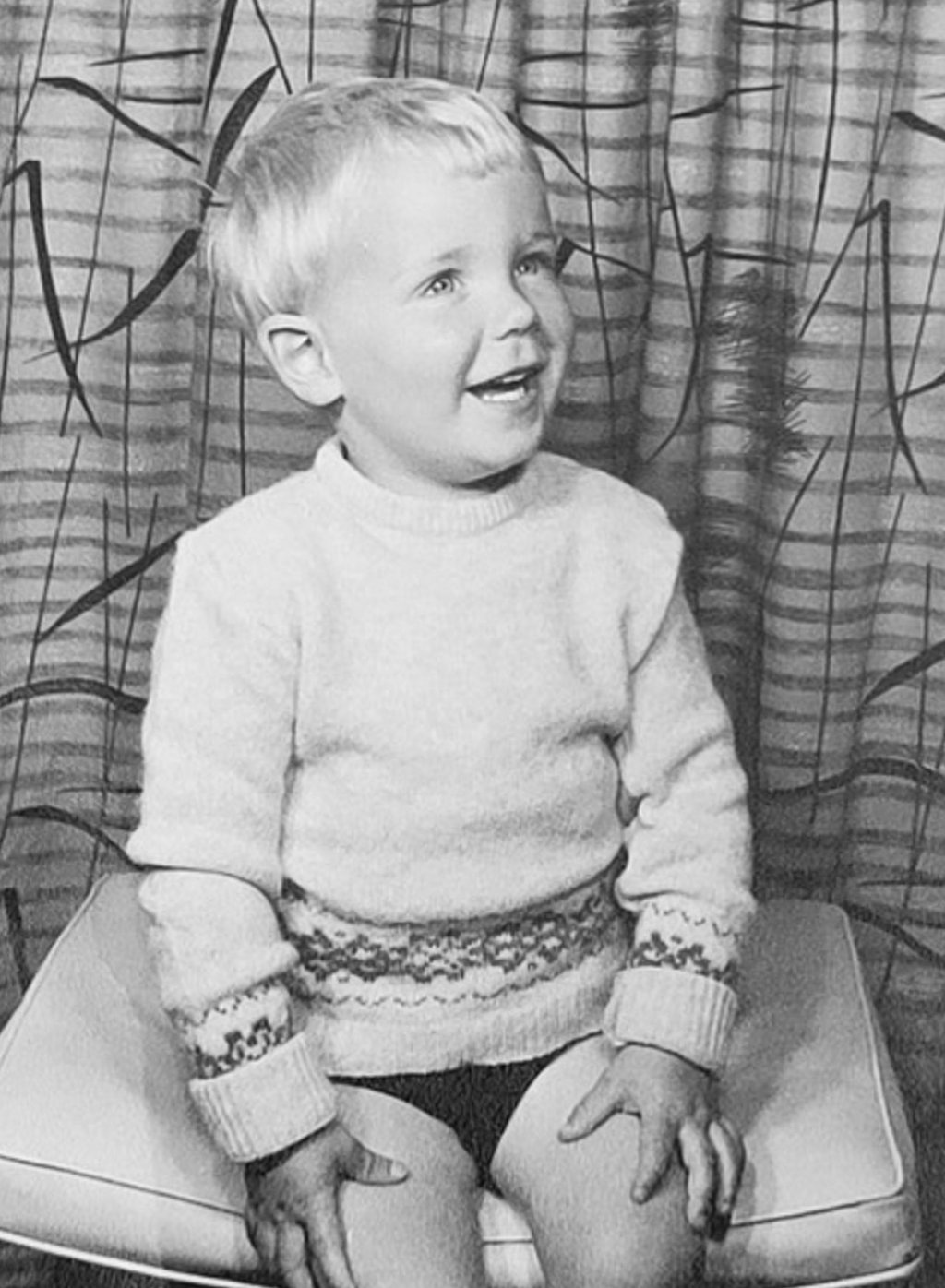

One of the quite beautiful things my parents did was that I don’t recall being told I was adopted, and nor does my younger sister. It was a natural part of family life before we were speaking beings. But obviously it makes you self-conscious about things, about identity, parenthood … you think, how does this fit with that?

My father worked in advertising. My mum was a great reader, I learned my love of reading and the arts and theatre from her. I was highly musical and my parents were not musical. They were wonderfully supportive about it but, still – where had it come from?

Dark start

I grew up in Buckinghamshire, in [central] England, very suburban, lovely green fields, middle middle-class. I went to a good grammar school – a state school – and had a great education. It was like (the 2006 film) The History Boys; that was almost exactly my experience, down to the fondling by a teacher in not particularly healthy or savoury ways.

There was one incident when I was 12, one when I was 15, both the same teacher. I’ve never talked about it before in a public setting. No, it didn’t make me secretive – I’ve talked about it with friends, I’ve obviously talked about it with my therapists. It wasn’t right and I said no. The guy ended up killing himself but that was later, not when I was at school.

And when I was 18, my clarinet professor fell in love with me. It wasn’t what I wanted. I suppose the thing that may be worth saying from a therapeutic point of view is these experiences of childhood are formative, they are difficult, but they also teach you resilience. They create patterns of coping that are both healthy and unhealthy. I would still say my schooling was happy, I learned a huge amount.

Faith in travel

There was a possibility that I might go full time to the Royal Academy of Music instead of Oxford. My father wrote me a letter, which I still have, about keeping my options open.