Then & Now | Hong Kong’s water supplies built by the British allowed the city to grow and thrive more than any other factor

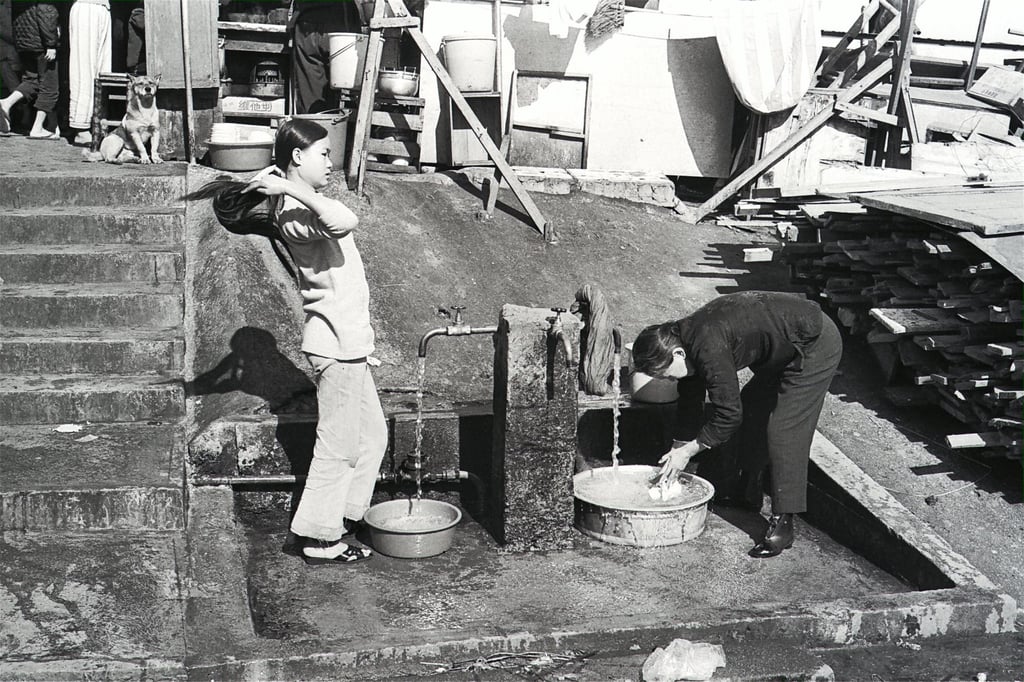

- Historically lacking a reliable water supply, Hong Kong developed from subsistence villages to a densely populated city thanks to its water infrastructure

- History’s more painful lessons demonstrate how critical the issues of water security were to Hong Kong’s survival in times of acute threat

A compelling alternative history of Hong Kong could be structured around that seemingly most mundane of life’s essentials: water.

From its initial provenance in remote hillside rivulets to its eventual release through urban kitchen taps, every stage reveals Hong Kong’s evolution from British rule’s mid-19th century beginnings to today’s urban conurbation – which only happened as a direct consequence of that administrative change.

These days, lazy journalism – and even lazier “scholarship” – too often asserts that Britain “took over the city”. This statement implicitly suggests “a city” existed for a hostile foreign power to expropriate, rather than the interconnected series of small, subsistence-level villages that were actually in existence on Hong Kong Island before European settlement.

Brief examination of Hong Kong’s topography reveals this is not somewhere a city would naturally occur – certainly not one of today’s population. Mountainous, with limited flat land and no significant rivers, lakes or other naturally occurring water sources, its basic geography alone militates against sizeable urbanisation.

Honest examination of this underlying fact makes much else about Hong Kong’s evolution from the early 1840s, and subsequent development into the present day, clear.