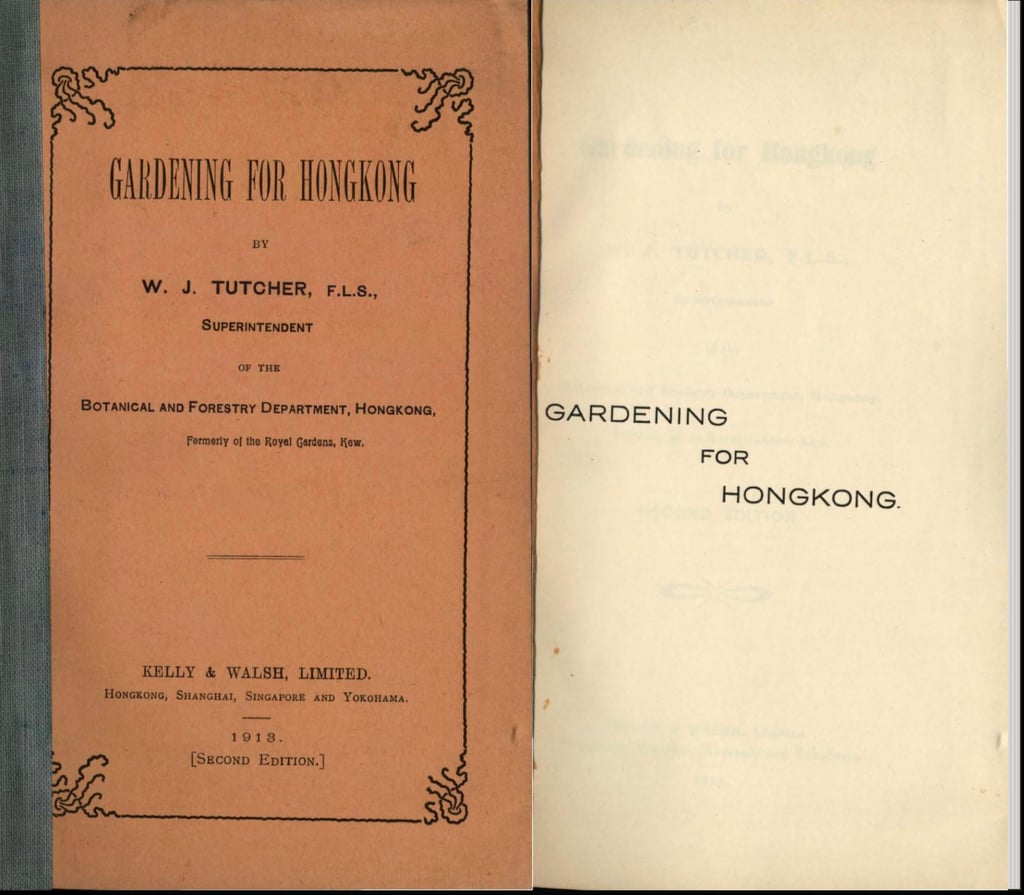

Then & Now | Hong Kong gardening manuals are time capsules that chart the city’s changes through the decades

- Early gardening books distilled horticultural expertise to reveal the city’s peculiarities, such as how Kowloon was better for growing than Hong Kong Island

- Today they serve as history books, with their lists of obsolete fertilisers and advice for post-war urban gardeners as Hong Kong’s population grew

From its mid-19th century urban beginnings, Hong Kong – regarded by most modern-day residents as a concrete jungle – has been home to generations of enthusiastic gardeners.

These individuals ranged from armchair horticulturalists who derived enjoyment from the efforts of others, to serious hands-on gardeners who were happiest when up to their elbows in soil and compost, staking up stray plants or roaming about with a watering can, secateurs at the ready.

In time, some gardeners became expert amateur botanists, with professional levels of specialist knowledge.

For newcomers to particular countries or climates, or recent gardening enthusiasts who want to experiment, local guidebooks are essential.

Lengthy distillation of personal, practical experience, combined with more specific information gleaned over time, either from friends or professional contacts such as nurseries and farmers, informs the best of these works.