How the West may be helping to shape Chinese cinema’s next new wave: two emerging filmmakers tell their stories

Qiu Yang and Chloé Zhao – who are among the Chinese filmmakers showing their work at Cannes this year – stress how much living and studying abroad widened their horizons and gave them a new focus

Make way, China’s young, self-taught digital filmmakers: another cinematic wave is breaking on the country’s shores.

And unlike their digital-savvy predecessors, these Chinese-born directors studied, lived, worked and made their breakthroughs overseas; let’s call them the O-Generation. What better place for this nouvelle vague to emerge than Cannes, where a country’s cinema is constantly rediscovered and reinvented?

Just like other “new wave” films from China and elsewhere, the Cannes entries of Qiu Yang and Chloé Zhao appear very distinctive.

The former’s A Gentle Night (2017), which debuts in the official short-film competition, is a 15-minute piece about a woman’s desperate search for her missing daughter in a provincial Chinese city; Zhao’s The Rider (2017), part of the independently organised Director’s Fortnight programme, is a feature-length film about a young cowboy’s life on a Native American reservation in South Dakota, in the United States.

What connects the two are the backgrounds of their creators, both of whom are making their second appearances at Cannes this year.

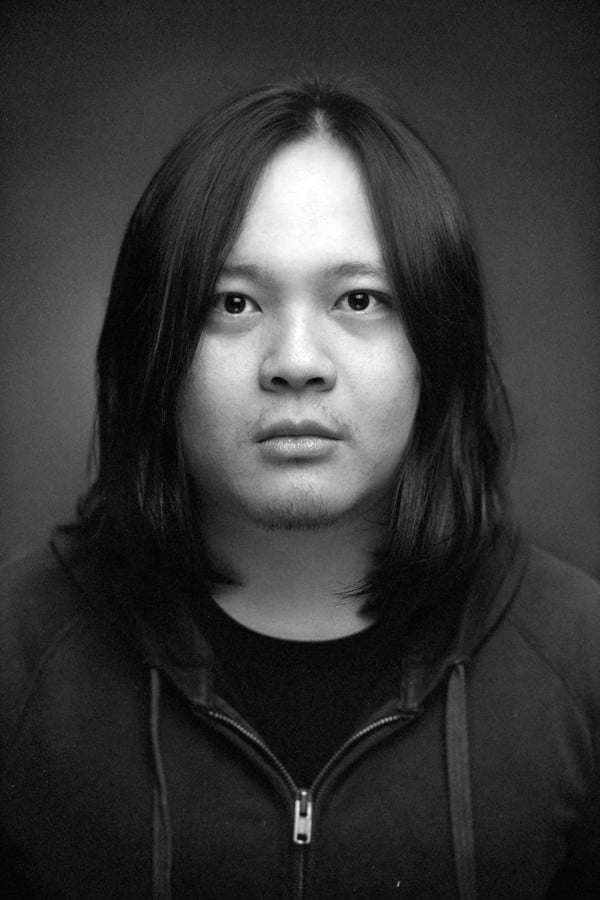

A native of Changzhou, in Jiangsu province, Qiu did both his undergraduate studies and master’s degree in Australia; Zhao, meanwhile, left Beijing for Britain as a teenager before relocating to the US to study. This phenomenon is relatively new in China, with parents now finding it easier – both financially and procedurally – to send their offspring abroad.

Qiu says his five-year spell in Brisbane and Melbourne altered his perspectives on life and filmmaking. With help from Australian friends, he completed Under the Sun, his graduate film at the Victorian College of the Arts, in 2015. Set in his hometown in China, the short film was selected as an entry in Cannes’ student-oriented Cinéfondation competition that year.

His first few months in Australia were tough. “There weren’t many Chinese students, so I had to work and talk in English all day every day. It improved my language rapidly,” he says.

He gradually eased into his new life, he says, by working on the sets of television commercial and film shoots – experiences that stood him in good stead as he focused on film direction while taking his master’s degree in Melbourne.

Zhao says she was a misfit when growing up in the Chinese capital. “I was a pretty free-spirited kid. I was part of a notorious group of troublemakers who didn’t do well in school, but had a great time exploring Beijing from the inside out,” she says.

After studying political science at Mount Holyoke College, in Massachusetts, in the US, Zhao switched to filmmaking at New York University. She spent three years living on and off a Native American Lakota reservation before beginning production on what would eventually become her debut, Songs My Brothers Taught Me (2015).

“I often feel like an outsider wherever I go, so I’m always attracted to stories about identity and the meaning of home,” she says.

Songs received its world premiere during the Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes in 2015 and travelled widely on the festival circuit. Zhao’s latest film, The Rider, is again set in America’s rural backwaters, this time among cowboys.

“They are so inherently American, and represent a way of life in the heartlands that is fast disappearing,” she says.

Now based in Denver, Colorado, Zhao says she has not followed the development of mainland Chinese cinema “as much as I should”.

“I’m heavily influenced by European and American cinema, but the further I get in my career, the more I find myself looking back East for inspiration,” she says. “I would love to return to China one day to make films. I’ve been away for too long, so I’ll need to spend some time back home before I can come up with an idea.”

Meanwhile, Qiu has returned to Changzhou, where, and in contrast to Australia, some of his fellow filmmakers are “normalising” the increasingly restrictive creative environment in China.

“Filmmakers are more interested in competing with each other,” he says. “They don’t speak out for fellow directors, nor [do they] help. Everyone is too busy earning their own share of this ‘booming film economy’.”

A straight talker, Qiu says his experiences overseas – and those of others – could be a harbinger of changes to come. “It is one of the most important things in my life, and my films,” he says. “Also, I think it is good that the state-owned film academy is losing its monopoly.”