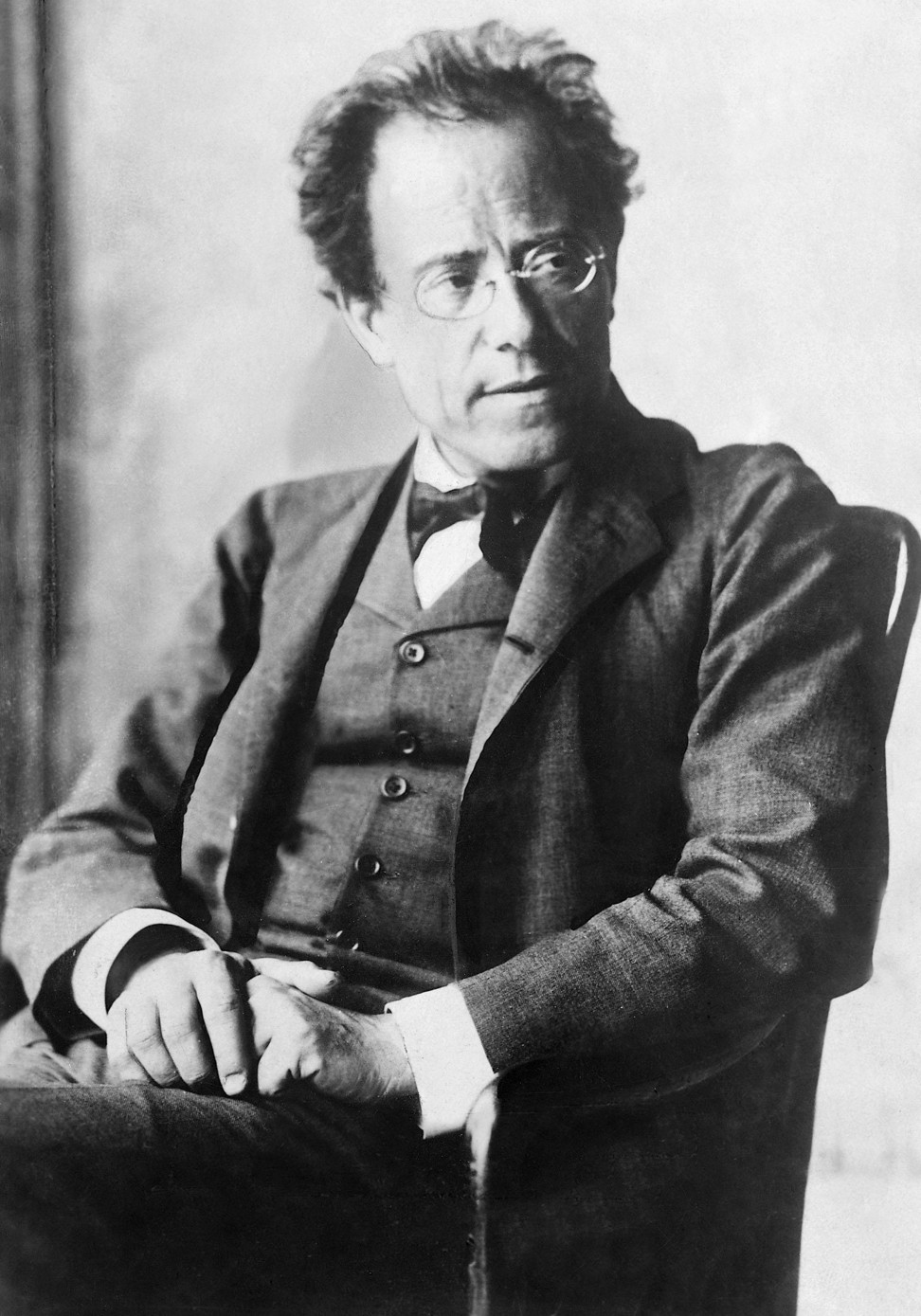

Flashback: Mahler (1974) – Ken Russell’s eccentric portrait of the 19th-century Romantic composer

Highly stylised and at times factually unreliable, Russell’s iconoclastic work shows a deep appreciation of Gustav Mahler’s creativity

Rather than depicting the lives of his subjects in the humdrum manner of most biopics, British director Ken Russell used the full arsenal of cinematic techniques to comment on the great composers in his films. Mahler (1974), which arrived on the heels of films and television programmes about Tchaikovsky (The Music Lovers [1970]), Elgar and Delius, is an emotive, eccentric film about the 19th-century Romantic composer that uses subversive imagery, camp excess and choreographed performance sequences to depict key events in his life.

Although many of the scenes are highly stylised, and there are factual inaccuracies, the film stays as true to the life of its subject as most conventional biopics. Russell’s deep understanding of Mahler’s music is evident, and the synchronicity between image and music provides a powerful, if unusual, experience for open-minded music lovers.

Robert Powell stars as Mahler, whose life story is told in flashback, via dreams and memories, while he journeys to Austria on a train. Russell analyses the composer’s creativity, and references key events in his life, such as his renunciation of Judaism at the behest of Richard Wagner’s widow, Cosima, a notorious anti-Semite. At the core of the flamboyant stylistics lies a story about Mahler’s relationship with his wife, Alma (Georgina Hale), who is aggrieved because he stymied her own creative instincts.

Russell was consciously iconoclastic, and relished shocking the British filmmaking establishment, which he refused to become part of. (They didn’t like him much, either.) Mahler is notorious for a scene in which Cosima, wearing a Nazi-inspired sadomasochistic outfit and wielding a whip, forces Mahler to kill a pig with a sword made from a Star of David and then eat its head. The scene, which is camp as hell, is directed in the manner of a silent movie from the 1920s, and is used to illustrate Mahler’s abandonment of Judaism.

Russell, whose films attacked authoritarianism of any stripe, also ran into trouble with the estate of Richard Strauss for depicting the German composer’s involvement with the Nazis in his crazed TV film Dance of the Seven Veils (1970).

Mahler is more of a cinematic essay than a life history – it seeks to be a comment more than straightforward document. Apart from when he consciously toned himself down, as in his 1989 adaptation of the D. H. Lawrence novel The Rainbow, Russell had no interest in naturalism, which he seemed to find dull and uncinematic. Lisztomania, his 1975 biopic of Franz Liszt, dispensed with reality altogether, depicting the composer and pianist as a rock star portrayed by Roger Daltrey, the lead singer of The Who.

Russell’s synthesis of music and image is at its most powerful in The Who’s rock opera, Tommy, which he directed in 1975.