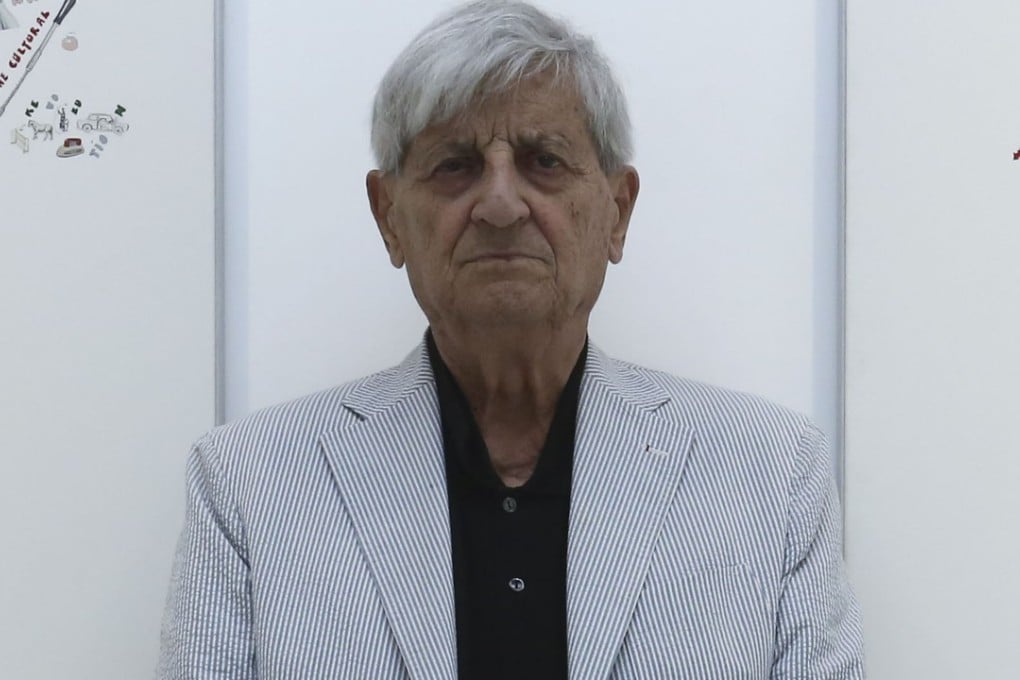

At 93, Italian artist Gianfranco Baruchello is still going strong

In Hong Kong for an exhibition featuring his art alongside that of his friend Marcel Duchamp, Baruchello talks about growing up under fascism, hitting the big time in the art world and why, in his 90s, he still works an eight-hour day

A child of fascism I was born in 1924 in Livorno, Tuscany, a port town by the Tyrrhenian Sea. I grew up immersed in the fascist mass hysteria until its fall, in 1945. My father was a renowned syndicalist, the director of the industrial union in Livorno, close to the government. He supported the idea of the mainstream superhero models typical of that historical era, and I was brought up in that environment.

To get closer to the fascist government, we moved to Rome in 1934. We lived in a large, bright flat right in front of Palazzo Venezia, Benito Mussolini’s residence. From our windows, we could see him addressing his speeches to the nation from his balcony. He was short and stout and gave me an unpleasant feeling every time I saw him. I was only 10 at the time, and it didn’t take long before I broke free from my father’s rigid beliefs.

Visions of war When I was 19 years old, I took my chance and ran away from Italy following my uncle – a diplomat – on his way to Odessa, Ukraine. There, carrying a diplomatic passport, I started to write and draw, documenting the retreat of the Italian army by the Don River. I witnessed death, pain, defeat, sorrow. Endless writing and drawing were my way to process all these emotions and reshape my vision of the world. In those challenging months, I began to develop my visual language. But when I got back to Rome, feeling lucky for being alive, I decided to complete my law studies at the university and tried for a couple of years to run my dad’s business. And I realised that art was my only possible direction.

I witnessed death, pain, defeat, sorrow. Endless writing and drawing were my way to process all these emotions and reshape my vision of the world

First impressions I never had a proper arts education. I never went to art school or had art teachers. I just started painting my own way. At the beginning, I used my fingertips. I would look at small details of objects that were part of my daily life, like the blade of a knife, and transfer the impression of it onto paper, with my bare hands. I would do that thousands of times, almost non-stop.