Bangladesh’s top art-collecting couple promote creativity and religious tolerance amid Rohingya crisis

Industrialist Rajeeb Samdani and wife Nadia’s Srihatta-Samdani Art Centre and Sculpture Park, opening next year, will give local and international artists much-needed space to showcase contemporary art and progressive ideas

Jet-setting, art-collecting Bangladeshi husband and wife Rajeeb and Nadia Samdani were in Hong Kong this month for a series of M+ museum talks on South and Southeast Asian art and design, and The Collector took the opportunity to obtain a first-hand update on their ambitious art centre, which is under construction in northeastern Bangladesh.

Industrialist Rajeeb, 43, is managing director of the Golden Harvest Group, one the biggest private companies in Bangladesh, with interests in food production, banking, insurance and property.

His family, like that of his wife, comes from Sylhet, which sits close to the porous border with India’s Assam state and shares with that region a legacy of British colonial tea gardens and a strong identity founded upon the Bengali language and culture.

This is Asia’s time now, and Bangladesh is one of the fastest growing economies here. We are on track to become a middle-income country, and art is part of it

Srihatta is the old, Indo-Aryan name for Sylhet, and use of the word in the art centre’s name is a nod to the multiplicity of traditions that the city and the 46-year-old nation of Bangladesh are founded upon.

Recent years in the conservative, Muslim-majority country have seen a rise in fundamentalism and attacks on Christians, Hindus and other minorities, and that has ramifications for anyone showing art.

In February, Polish artist Pawel Althamer led residents of a Sylhet drug rehabilitation centre in creating a giant sculpture called Rokeya, in tribute to female Bengali writer Begum Rokeya, an advocate of women’s rights.

Some local imams expressed concern that the artwork depicted a human figure, which goes against Islam’s aniconism (proscription against the creation of images of sentient beings). The Samdanis talked them round, stressing links between the bamboo construct, draped in colourful fabric, and folk ornaments employed in local festivals.

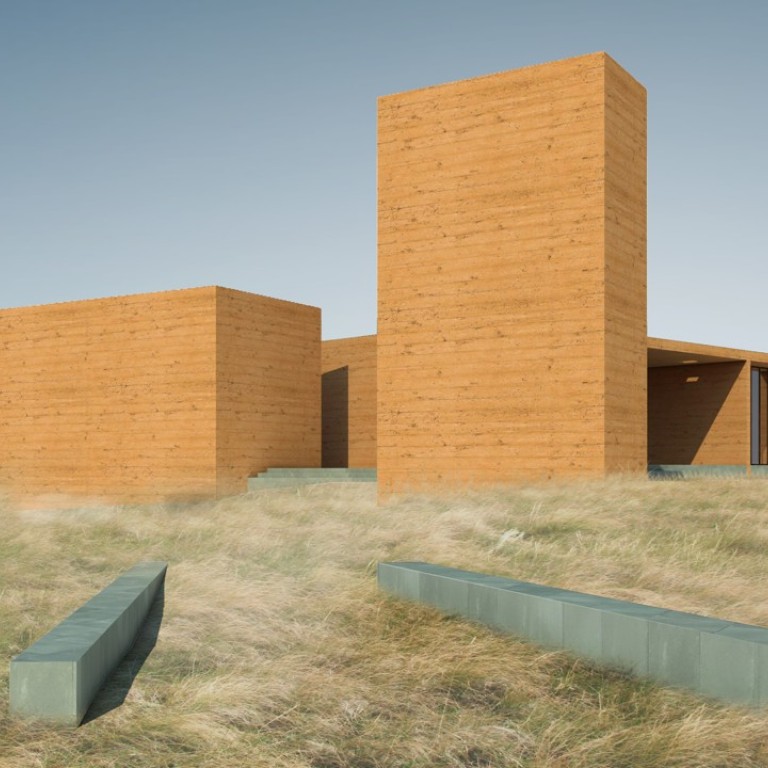

As well as an expansive sculpture park, when the centre opens it will feature pavilions built to house the large installations that the Samdanis have acquired since they turned to collecting 11 years ago, including Experiment in F# Minor (2013), a table-like structure measuring 2.5 metres by 1.8 metres and covered with dozens of sensor-activated loudspeakers, by Canadian artists Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller.

“We keep a lot of our collection in our home in Dhaka, which is open to the public by appointment,” says Nadia, “but there are some pieces that are simply too big to be shown at the moment.”

Rajeeb, meanwhile, describes his country as a neutral platform for showcasing domestic and international creativity, and says its government encourages the arts. “We don’t often take sides on regional issues,” he says of Bangladesh, “so we can show art by anyone.”

What’s more, with the domestic economy on a roll, the Samdanis believe they are presenting a new face of their nation to the world – one that is not all about poverty, cyclones and floods.

“This is Asia’s time now, and Bangladesh is one of the fastest growing economies here,” says Rajeeb, who also sits on the International Council of the Tate Museum, a position he uses to encourage the London institute to acquire more artworks from South Asia. “We are on track to become a middle-income country, and art is part of it. We launched the Dhaka Art Summit in 2012, to help local audiences understand contemporary art, and for local artists to get themselves known internationally.”

In February, the fourth edition of that biennial summit will be held, at Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy in the capital, and focus on Bangladesh’s links with Southeast Asia – a deliberate move when the country’s relationship with Myanmar is in the spotlight.

“There are people who say that, as we have around 180 million people in the country, we can absorb another million,” Rajeeb says. “The government opened the border to the Rohingyas because the people of Bangladesh wanted them to come. We are Muslims, and we are also a country that has learned from day one what it’s like to be on the fringe.

“We used to be called Pakistan’s dustbin, or the ‘bottomless basket’. Now that we are economically better off, we are in a position to help others.”