Giuseppe Tornatore’s Cinema Paradiso explores the magic of movies

The popular Italian film is an ode to youth, old cinema and the communal experience of movie-watching

One of Italy’s most popular films, Giuseppe Tornatore’s Cinema Paradiso (1988) is an ode to youth, to the movies, and to the pleasures and perils of small-town life. Cineastes have long adored the way it puts films and film-watching right at the centre of life, where they act as an escape from drudgery, an education about the wider world, and are even an erotic force.

Most pleasing is the way the film’s titular theatre serves as a focus for the town’s community, bringing all echelons of the social strata together for a shared experience. The silver screen never looked so poignant and so powerful.

The movie’s subtle, easy-going nature belies a complex, multilayered structure. The story is told in flashback form by esteemed Sicilian film director Salvatore “Toto” Di Vita, who receives a call in Rome informing him of the funeral of his old friend and mentor Alfredo (French actor Philippe Noiret), once the projectionist at the movie palace Cinema Paradiso.

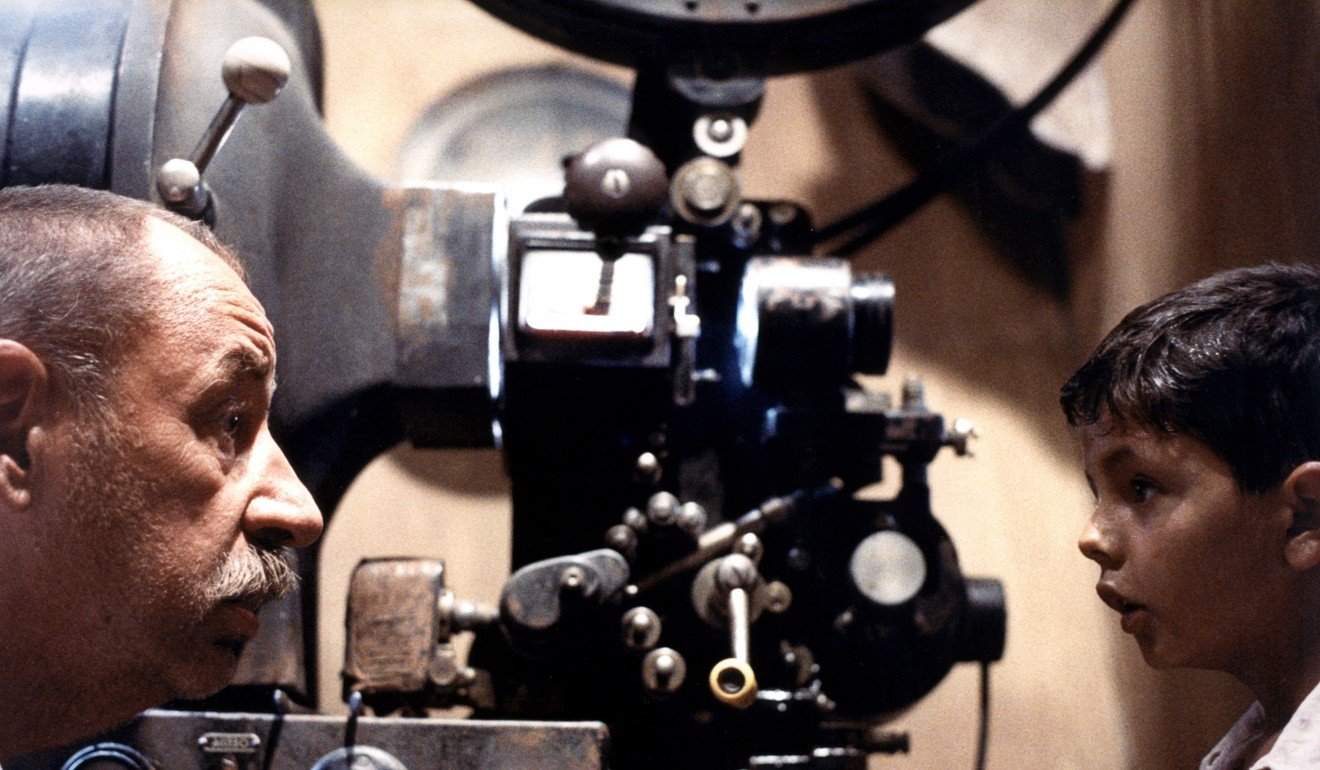

Toto reminisces about his youth, when his fascination with the projection booth led to a friendship with the ageing Alfredo, who taught him how to work the machine. The bond between the young Toto (played by Salvatore Cascio) and Alfredo grows deep when a film catches fire – acetate film was flammable – and blinds the old man. As no one else can work the projector, Toto takes over Alfredo’s job. But Alfredo persuades Toto to leave the town for the possibilities of Rome, and he has never looked back – until now.

Cinema Paradiso is gentle yet unsentimental and contains numerous clips from classic films by Charlie Chaplin, Jean Renoir, Luchino Visconti, et al. A memorable subplot sees a conservative Catholic priest censor kisses in movies by ringing a bell, indicating the projectionist must snip out the offending scene from the film roll.

Tornatore has said that Cinema Paradiso is semi-autobiographical, in the sense that he, like Toto, was fascinated by the mysteries of the projection booth as a child, although many of the details came from research.

The film’s genesis is referenced in a scene where Toto watches the cinema of his youth demolished – Tornatore had that experience, and it sparked the script.

The film exists in a few forms, mainly a 2002 173-minute director’s cut and a 124-minute version. Another long version bombed on its original release in Italy, forcing the cut. The resulting short version found success around the world, but Tornatore favours the original Italian version, which has been lost. The movie’s final montage of kisses – Alfredo’s compilation of the scenes cut by the priest – remains a delight in any version.