How an anti-Maoist French film director ‘hijacked’ a Hong Kong martial arts film

- Can Dialetics Break Bricks? takes kung fu potboiler Crush and positions it as a confrontation between the state and revolutionaries

- René Viénet was inspired by a distaste for authoritarian rule and an appreciation of Chinese-language cinema

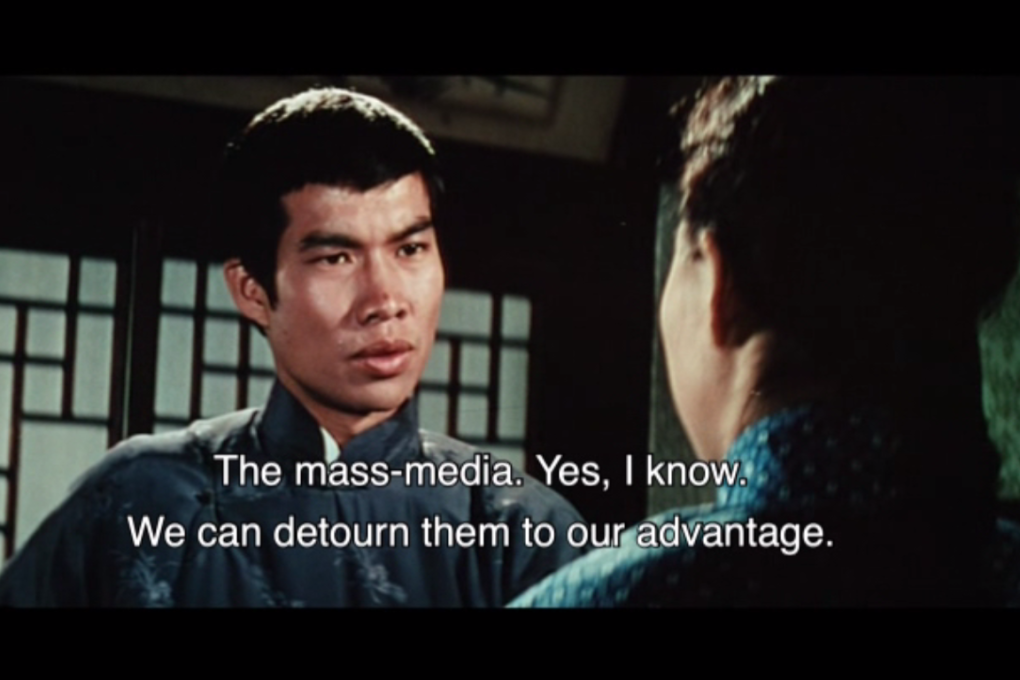

“A toast to the exploited: for the termination of the exploiters,” the narrator says, as the camera zooms in on actor Jason Pai Piao. He strikes a pose, then performs a dizzying array of kung fu moves – a thinly veiled allusion to his athletic prowess, unfettered masculinity and action-hero credentials – as he gets set to give some baddies a thrashing.

So far, so predictable for a martial arts flick. Then comes the unexpected. “He looks like a jerk, it’s true,” continues the narrator, as Pai shoots the camera another macho gaze. “But it’s not his fault, it’s the producer’s. He’s alienated and he knows it. He has no control over the use of his life. In short, he’s a proletarian. But things are about to change.”

This is the eccentric opening sequence of Can Dialectics Break Bricks?, the 1973 directorial debut of French sinologist René Viénet. Applying the politically charged approach known as “détournement” – in which mainstream media is appropriated and injected with anti-establishment values contrary to the original material – Viénet “hijacked” Crush, a 1972 Hong Kong kung fu potboiler shot in South Korea, replacing its Mandarin dialogue with a French soundtrack discussing Marxist ideas.

Directed by veteran Hong Kong-based Chinese filmmaker Tu Guangqi, Crush was a story of confrontation between brutal colonialists and taekwondo warriors in Japanese-ruled South Korea, in the early 20th century. With the rebels facing annihilation, Pai’s character – a sort of Chinese lone ranger – arrives to save the day. In Viénet’s version, however, the battle is between swaggering “state bureaucrats” and anarcho-syndicalist revolutionaries.

What was originally a piece of shallow, sensationalist entertainment – albeit with a whiff of anti-imperialist sentiment – was transformed into a dense political tract about class struggle.