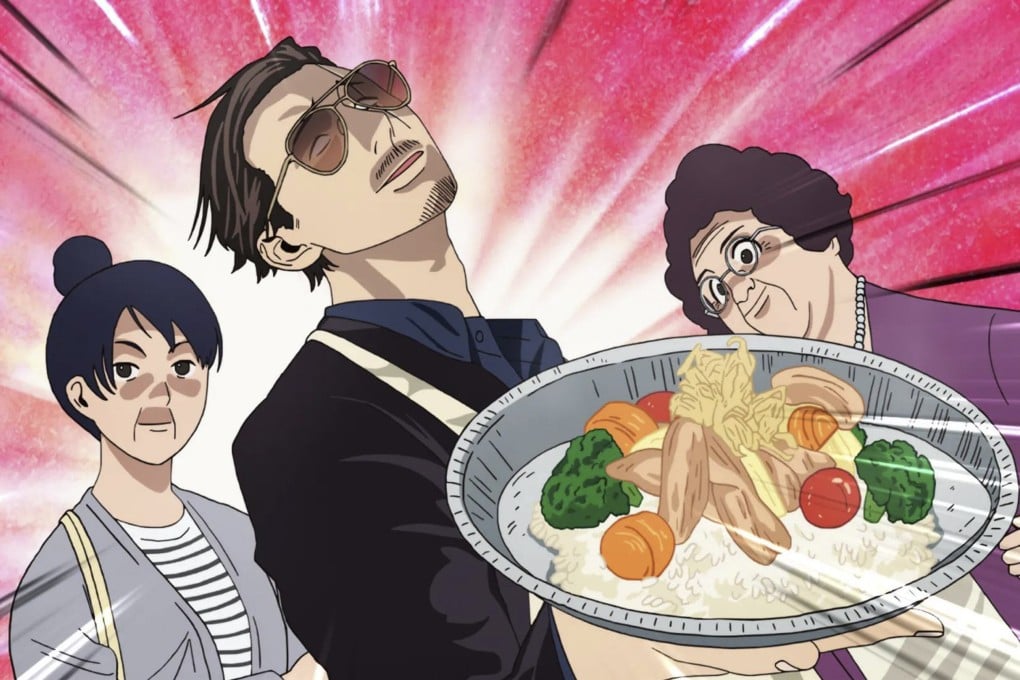

What a view | The Way of the Househusband is a Netflix anime comedy for our changing times

- A former yakuza swaps the gangster life for one of blissful domesticity in this eccentric Japanese production with a heart of gold

- The show is based on the manga series of the same name written and illustrated by Kousuke Oono

If you want proof that machismo is turning into something you might come across only on old VHS tapes, sample some male domestic bliss in The Way of the Househusband (Netflix). When even the most liberally tattooed ex-yakuza can throw on an apron, feed the cat, make dinner for his wife, operate the vacuum cleaner, volunteer for a spot of neighbourhood babysitting, bake cookies and then sort out the recycling, you know times they are a-changin’.

Agreed: this eccentric Japanese production is an anime comedy, but its five-part first series is not without its home truths. With so-called traditional roles reversed, Tatsu (once a gangster known as the Immortal Dragon, who still looks intimidating enough to instil fear in rivals from his previous life) keeps the household running while Miku, his independent, career-minded partner goes out to work (and wears the trousers). In a time of increasing gender equality and inversion of norms, this might even offer a blueprint for future human relations.

Based on the manga series of the same name written and illustrated by Kousuke Oono, The Way of the Househusband might be simple and somewhat static in its animation, but this optimistic fable of the yakuza with a heart of gold is undeniably appealing in its unexpectedly sunny view of life. And flashbacks to Tatsu’s alter ego as an implacable criminal allow a handy “now and Zen” contrast, his unlikely transformation being confirmed when aerobics, yoga and do-it-yourself (rather than doing people in) enter his life.

“Being a househusband ain’t no joke,” declares Tatsu, on his hands and knees, polishing the floor and no longer seeking the way of the dragon, ninja or gun.

Perhaps men are finally starting to understand the rigours of domestic engineering.