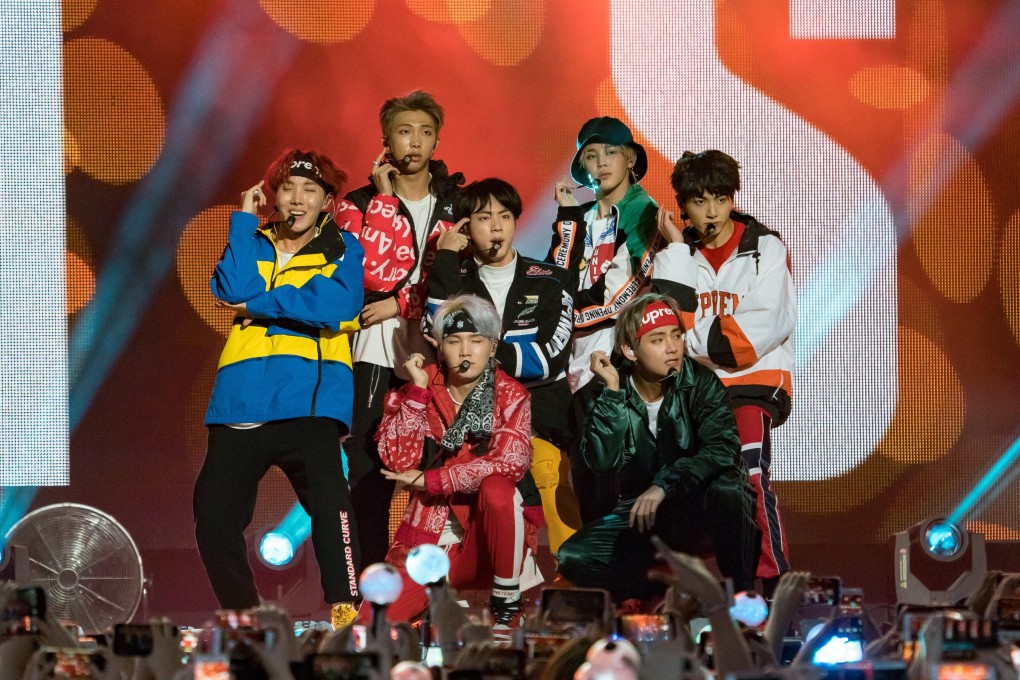

BTS interview: the K-pop giants on Army, military service, masculinity and their early days before conquering the world

- BTS members RM, Suga, J-Hope, Jin, V, Jimin and Jungkook open up about transcending K-pop stardom to become a global phenomenon

“This is a very serious and deep question,” says RM, the 26-year-old leader of the world’s biggest band. He pauses to think. We are talking about utopian and dystopian futures, about how the boundary-smashing, hegemony-overturning global success of his group, the wildly talented seven-member South Korean juggernaut BTS, feels like a glimpse of a new and better world, of an interconnected 21st century actually living up to its promise.

BTS’ downright magical levels of charisma, their genre-defying, sleek-but-personal music, even their casually non-toxic, skincare-intensive brand of masculinity – every bit of it feels like a visitation from some brighter, more hopeful time.

What RM is currently pondering, however, is how all of it contrasts with a darker landscape all around them, particularly the horrifying recent wave of anti-Asian violence and discrimination across a global diaspora.

“We are outliers,” says RM, “and we came into the American music market and enjoyed this incredible success.”

In 2020, seven years into their career, BTS’ first English-language single, the irresistible Dynamite, hit No 1 in the United States, an achievement so singular it prompted a congratulatory statement from South Korean President Moon Jae-in. The nation has long been deeply invested in its outsize cultural success beyond its borders, known as the Korean wave.

“Now, of course, there is no utopia,” RM continues. “There’s a light side; there’s always going to be a dark side. The way we think is that everything that we do, and our existence itself, is contributing to the hope for leaving this xenophobia, these negative things, behind.”