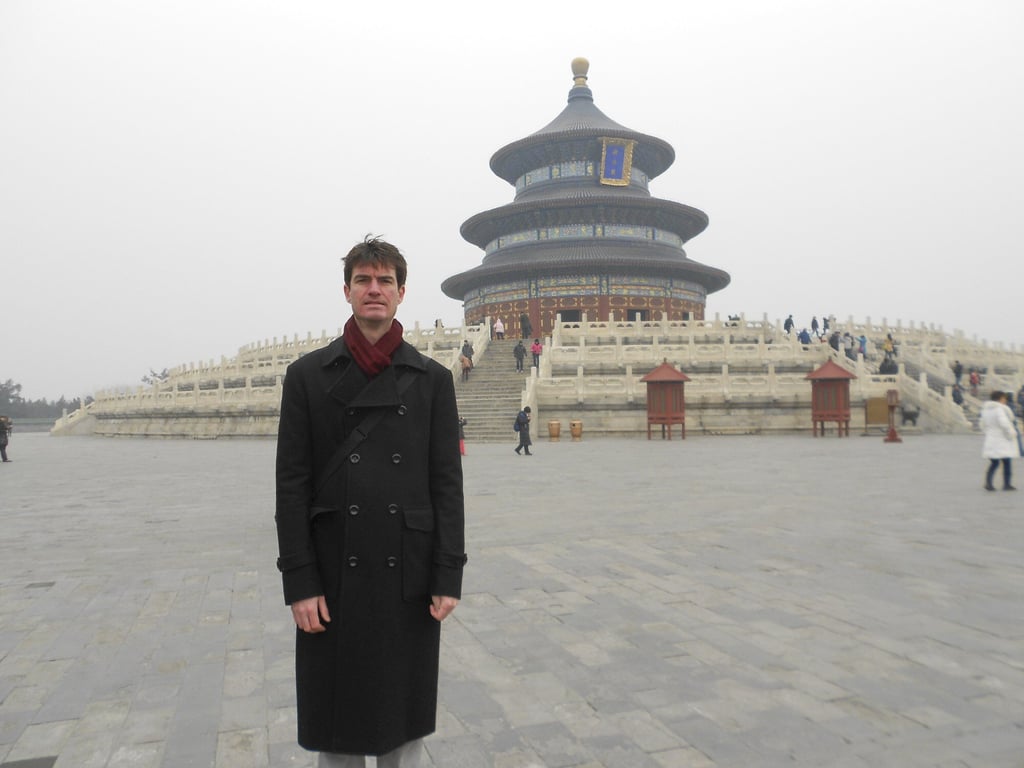

Profile | How an American fell in love with China and Chinese – literary translator Eric Abrahamsen, now back home, looks back on innocent times in Beijing

- Eric Abrahamsen was ‘book dependent’ by the age of six; on a trip home to the US from New Zealand, China ‘lodged itself’ in his mind, he tells Thomas Bird

- He moved to Beijing for university and started reading Chinese fiction, eventually becoming a translator. He recalls a time of openness and ease that’s gone

I was born in 1978 and grew up in Seattle, Washington, in the United States. It was a normal middle-class upbringing and I don’t remember all that much, apart from reading indoors while it was raining outside. I was “book dependent” by the age of six. I loved adventure stories, sci-fi and fantasy – you could say I was already a cerebral traveller.

Nothing much out of the ordinary happened until my parents, Laurel Harmon and Barry Abrahamsen, moved my younger brother Peter and I to New Zealand.

Journey to the East

My parents travelled a lot before they had us. After we were born, they became a bit sedentary, but it was always important to them that we had an international outlook. So, in 1986, my father applied for a transfer at the computer company he worked for, Unisys, and the whole family relocated to Wellington for two years.

New Zealand was beautiful, like the Pacific northwest but with more wind and less rain. It was the first time I really became aware of myself as an American, though that didn’t mean much to me then.

Years later, there were a few moments in Beijing where a place triggered a childhood memory and I sensed I’d been there before.