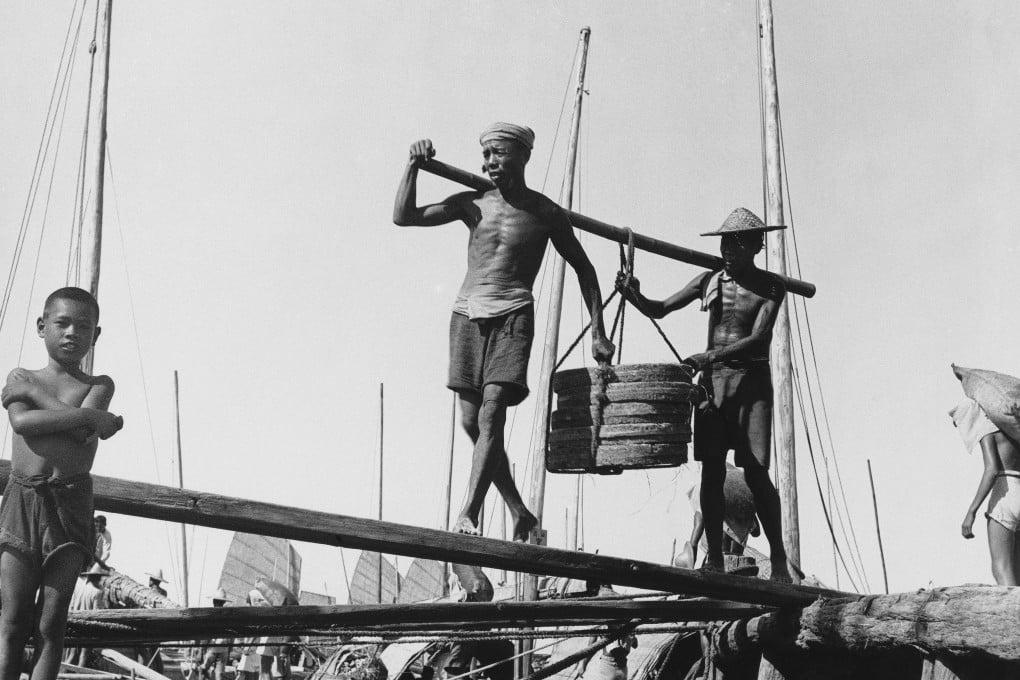

Photos of Hong Kong in the aftermath of World War II capture the city in all its grimy glory

- Arriving in 1946, Hedda Morrison may have spent only six months in Hong Kong, but the German photographer left behind a unique, wide-ranging photographic record

On September 21, 1946, German-born photographer Hedwig Marie “Hedda” Morrison arrived with her husband in Hong Kong, aboard the Hanyang, after spending 13 years in Beijing, where she had found an affinity with the Chinese. The couple would remain in the colony for only six months, but Morrison would leave behind a unique and wide-ranging photographic record.

Morrison was known for her lifelong gritty resolve, much like that mirrored in a stoic shopkeeper she had photographed in Hong Kong, a woman little older than Morrison herself.

That September afternoon, after making landfall at Waglan, an island to the southeast of Hong Kong, the Hanyang had threaded the narrow gap at Lei Yue Mun. To port and starboard, respectively, were Shau Kei Wan’s fishing junk anchorage on Hong Kong Island and a war-denuded Devil’s Peak in Kowloon. Morrison would later take detailed, almost topographical, photos of both places.

As the Hanyang proceeded up-harbour that day, Morrison’s gaze took in Quarry Bay and Swire’s Taikoo Dockyard, then Causeway Bay, onto HMS Tamar, where above the naval base stood Victoria Barracks – the site today of the Asia Society Hong Kong Centre.