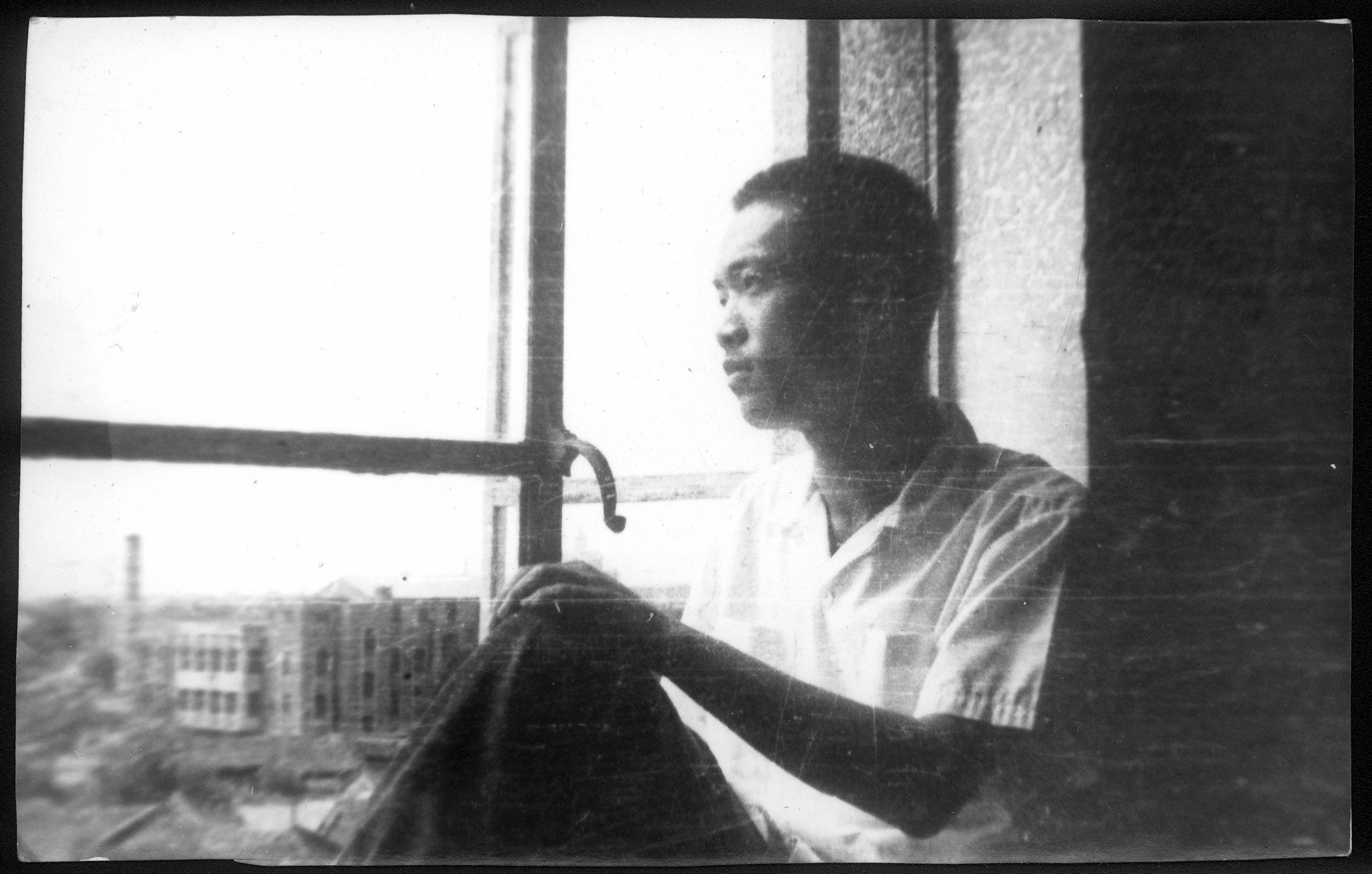

Profile | From a youth in the Cultural Revolution to a photographer and critic, one of the best known in China: the life of Bao Kun

- The son of a former Nationalist military officer, Bao Kun was sent to work in the photo section of a Beijing department store, where he spent nine years

- Bao became a photographer, shooting the album cover for a famous musician, then a curator, critic and mentor to young photographers, he tells Thomas Bird

My father, Bao Fengchi, was an educated man, who spoke English and wrote books on military strategy in his youth. He rose to become a senior officer in the Northeastern Army under the Fengtian clique, one of many opposing military factions in the warlord period.

In 1928, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek led the Northern Expedition and unified China under the Kuomintang. (The Old Marshal) Zhang Zuolin was killed on his way back to Manchuria and his son, (the Young Marshal) Zhang Xueliang, was made commander of the region.

My father was serving in Shenyang when, in 1931, the Japanese attacked. Zhang did not allow any resistance, letting the people retreat south instead.

That’s essentially how I came to be born a Beijinger of northeastern stock.

Early birds

I was born when my father was almost 50, in 1953. I was the fourth son in my family. Due to my father’s past he was deemed a counter-revolutionary and we grew up poor. I was raised in the hutongs with no material comforts, not even a ball to play with. One of my first memories is of seeing people killing sparrows (part of Mao Zedong’s Four Pests campaign in 1958).

Hong Kong domestic helpers invited to contribute photos for homage to them

My elder brother, Bao Chang, who’d joined the revolution when he was 16, helped exonerate us. He became a cadre after the Communist Party’s victory in 1949. Later, he became a professional writer and was able to support some of my living expenses.

He was knowledgeable, with a firm base in classical Chinese and helped shape my world view as both a lover of books, and something of a rebel.

Photo opportunity

I had read many Russian, French and Chinese classics such as Journey to the West before 1965. After the Cultural Revolution started, in 1966, social order began to fall apart. Many books were banned.

Beijing emptied of anyone older than me as students were all sent down to the countryside to learn from the masses. This led to a shortage of workers in the city so, in 1970, it was decided to start assigning people city jobs. After graduating middle school, I was the last of my school friends to be assigned. Some were sent to a brick factory.

I hoped to be a soldier, but I was sent to work at the Xidan Department Store, a huge commercial block established during the Republic of China that had become a state-owned enterprise in the 1950s.

After some months of training we were assigned a department. Some people went to textiles, others went to work in the canteen. I was sent to the old photo studio, which had been renamed the photo department. I worked there for nine years.

In the dark

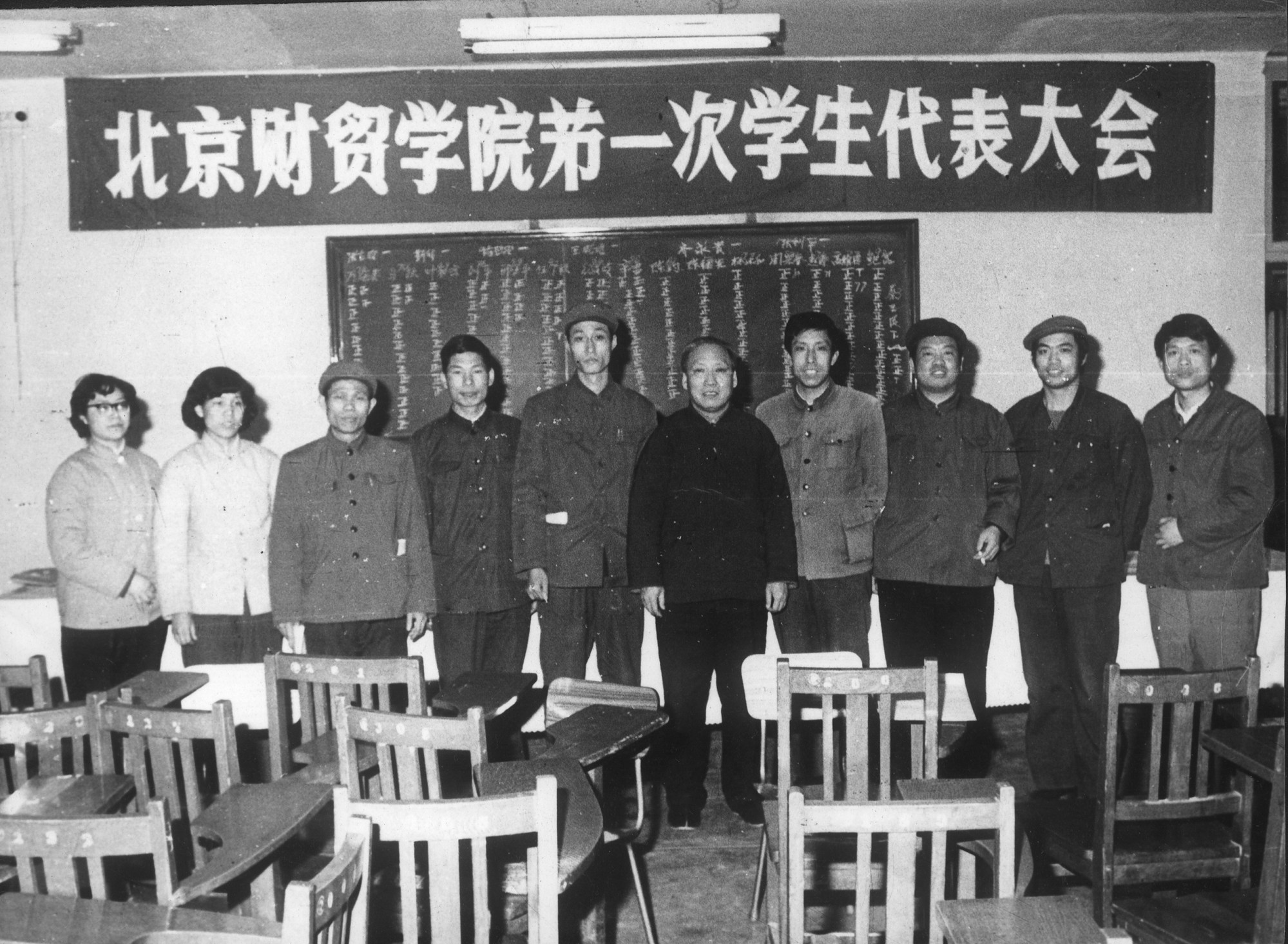

The university entrance examination was brought back in 1977 and I started applying, even though I was already past the age when one would usually go to university and I’d missed out on many elements of a normal education.

I failed the first year. In 1978, I failed again. The next year was my last chance to get in, so a friend recommended I apply to Beijing Institute of Finance and Trade as economics was not a popular major back then. I aced the exam.

Within three months of my undergraduate year, a man from the academic affairs office came to me and asked if I’d worked in a photo studio before. As I had, he said the school needed to buy some photography equipment and asked me to help.

I got them the cameras they needed. But as nobody knew how to use them, whenever the school held a meeting, I took the pictures. This way, I got to spend all my spare time in the dark room.

Night and day

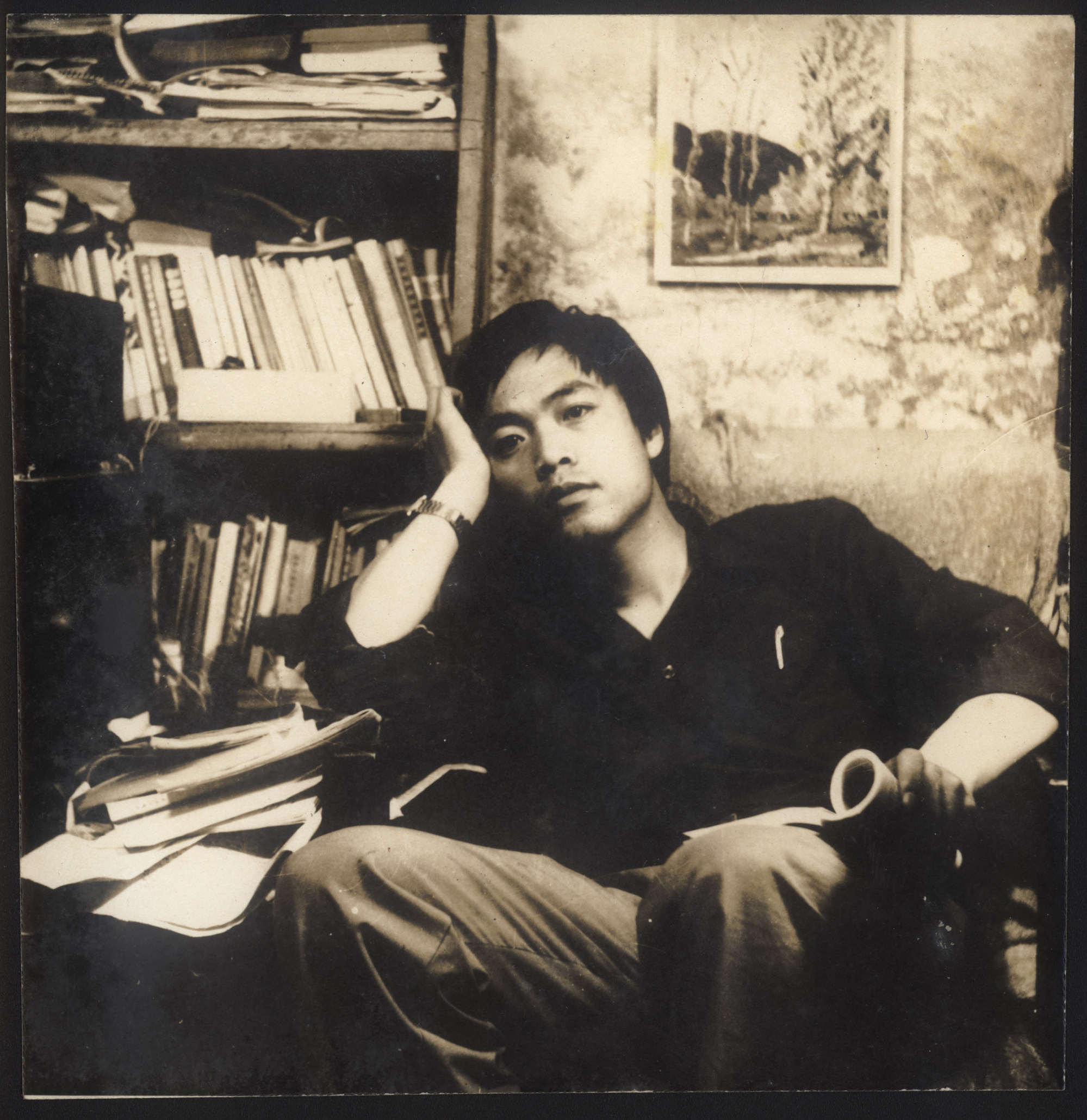

The 1980s in China were as different from the 1970s as night is from day. Bookshops filled up with translations of foreign books and people would line up outside. A cultural scene blossomed in Beijing and I made friends with most of the major artists, writers and musicians of the day.

I became a relatively influential photographer. The musician Hou Dejian came to mainland China from Taiwan. In 1984, he was preparing to release an album, New Shoes and Old Shoes. I shot the cover artwork and we became good friends.

I graduated in 1983 and started to teach aesthetics and photography at the University of Science and Technology Beijing. By the end of the decade, I was doing well enough to buy a car when most people just had a bicycle. I remember I’d paid the auto broker and had gone to pick it up from the warehouse in Tianjin Port when things came to a head in Tiananmen in 1989.

German detour

A lot of people started leaving China after that. Some feared the economy would falter. I wasn’t so concerned but decided to leave my job in 1990 and go to Germany, where I had friends.

It was refreshing living in Frankfurt, on the banks of the River Main. Germany made an impression as a developed society that balanced traditional and modern culture well. I even liked the food. I admired day-to-day politeness and how law abiding people were. I especially liked how often people read books in public.

My situation was not as desperate as many Chinese as I had some savings so I had time to enjoy myself. It was in March 1992, when I bought a copy of the European edition of Sing Tao Daily at Frankfurt railway station, that I decided to come home. The cover story concerned Deng Xiaoping’s southern tour. It was clear China wasn’t going to fall apart, and I returned in 1993.

All eyes on China

The 1990s was another miraculous decade in China. Nobody was thinking about politics, they were thinking about making money. As I’d left a prestigious state job I couldn’t return to it, so I ended up working in advertising for a few years.

After China joined the WTO in 2001, the world started to take an interest in what was happening and photography offered an eye into China. I moved into media, working for a time on a photography segment for China Central Television.

The first official photography festival in China, Pingyao International Photography Festival, was also held in 2001. I went to the third session as a member of the media. In 2005, I was invited back as a special guest.

Putting photography on the map

Since the early 2000s, I’ve been able to dedicate myself to the Chinese photography world full time. In 2004, I served as chief curator at Wuyishan International Photography Week and, in 2005, I curated the Guilin International Photography Festival. Since 2006, I’ve been involved in the Lianzhou Foto festival, in Guangdong province, often participating in the planning and selection stages.

In 2009, some people from a small city in Zhejiang province asked me to help them transform a local photography event into an international photography festival. Over the past decade, we’ve successfully put the biennial Lishui Photography Festival on the global art map.

Plastic China

I helped him complete several works, the most important of which were Beijing Besieged by Waste (2011) and Plastic China (2016). The former is a photographic series of the rubbish dumps in Beijing. It was exhibited at Lianzhou and won the grand prize. It attracted the attention of Premier Wen Jiabao, who promoted a nationwide emphasis on rubbish disposal.

In 2016, Wang’s documentary film Plastic China won an award at the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam, and also attracted huge attention in China, and influenced the decision to stop processing foreign garbage waste after more than 30 years.

Mind the gap

I think of reading as a kind of kung fu, a form of self-discipline, a practice to master. I began writing in the 1980s. The impetus came from the gap I perceived in quality between Chinese photography and international photography. I hoped to improve the scene through criticism.

I edited Photographing China – Highlights of 50 Years of Chinese Photography in 2006, published the anthology Time of Restlessness in 2008, and the anthology Watching and Rewatching – Contemporary Image Culture in 2009. The most important of these is the last one, which is basically my perspective on the historical, social and cultural role of photography as a medium. It has been quite influential in China.

‘Heartbreaking’: dog’s death the spur for photographer’s pet portraits

Photographic memories

I’ve been lucky. I will be 70 years old in 2023, I’m happily married and both my children are studying and working in the US. When I was born, China was an agricultural country. The home where I lived was only about 800 metres from the ancient city walls, and the countryside was not far from the wall. The transformation of China in my lifetime has been too fast and many problems stem from this, including widespread injustice.

The rise of Chinese contemporary photography has coincided with the rise of China. There have been many excellent photographers who’ve managed to reflect this era in their own, distinctive way, including Li Xiaobin, Jin Bohong, Ren Shulin, An Ge, Hu Wugong, Hou Dengke, Wang Qingsong, Liu Zheng and Wang Jiuliang.

The world’s curiosity about China has aided this growth, but also commercialised it, as some Chinese photographers have pandered to Western tastes. Nowadays, the ubiquity of smartphones highlights photography’s role as the “second language” of human speech and memory.

Yet, as a medium for exploring and questioning trends, photography will continue to have a special part to play in the years ahead, which is what I will dedicate my attention to moving forward.