- Hong Kong Ballet production Coco Chanel: the Life of a Fashion Icon dramatises the rise, emancipatory designs and controversies of the legendary couturier

“Be afraid of her!” choreographer Annabelle Lopez Ochoa tells Hong Kong Ballet’s female dancers, as Coco Chanel stalks around her workshop in the rehearsal studio at Kwai Tsing Theatre, cigarette in hand, terrorising the seamstresses.

A few moments later, as Chanel gives grudging approval to one girl’s work, Lopez Ochoa adds, “See, she’s not just a bitch.”

Portraying the various aspects of such a famous historical personality is only one of the challenges facing the choreographer, currently in Hong Kong to create a new, full-length work for Hong Kong Ballet, Coco Chanel: the Life of a Fashion Icon.

As well as helping with funding, this means the work will be seen on at least three continents and, with its world premiere at the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts’ Lyric Theatre, from March 24 to 26, promises to generate plenty of buzz for the Hong Kong Ballet.

She prefers to use historical figures “as opposed to women who were invented – mostly by male writers”, she says, “because their stories come with a lot of hardships and difficult decisions. Not always decisions that you’re proud of. So that’s already very operatic and theatrical.”

Given Chanel’s long life (she died at the age of 87) it is impossible to cover everything – “I’d need a four-hour ballet!” – so while Lopez Ochoa is using a chronological approach, she will focus on three themes over two acts: the way Chanel changed women’s clothing to give them greater freedom; her love life; and her passion for money.

Born Gabrielle Bonheur Chanel in Saumur, France, in 1883, the designer’s childhood of poverty and hardship (her mother died when she was 11 and her father abandoned her to an orphanage) was followed by years of struggle working as a seamstress and singing in cabarets.

In 1906, her fortunes changed when she became the mistress of the wealthy Étienne Balsan, then, three years later, of his English friend, Arthur “Boy” Capel.

Capel was the great love of Chanel’s life. After his death in a car crash in 1919, Chanel would say that “in losing him, I lost everything”.

It was Capel, a self-made man, who sensed Chanel’s potential and financed her start in business. In 1910, she opened a shop selling hats in Paris, followed by boutiques in Deauville (1913) and Biarritz (1915), where her revolutionary approach to women’s clothing propelled her to the forefront of the fashion industry.

“It’s always about the simple line,” says Lopez Ochoa. “So that’s how I want my choreography to be – simple lines.”

Despite her many love affairs, Chanel never married. One reason, says Lopez Ochoa, was that the men she was involved with when she was young were upper class, and so expected to marry within their own milieu. Both the Duke of Westminster and Capel married other women while continuing their liaisons with Chanel.

Having wealthy lovers may have enabled Chanel to launch her career, but Lopez Ochoa says the fashion designer “hated that men gave her money and that she was dependent on them. So it was always, ‘I need the money to move up in the world but I don’t want it to be something that makes me dependent on you’.”

Lopez Ochoa knew she wanted to be a choreographer from the age of 11, when her ballet teacher told the class she was giving them an hour with the pianist, and to each create one minute of choreography.

“I’d never even heard that word,” she says. “My piece was bad but that one hour felt like two minutes. Every time I come into a studio, anywhere in the world, I’m in the same white studio with the windows behind me.”

The scene with the seamstresses is complicated, involving 12 dancers moving 12 tables on castors around the stage, and winching lengths of fabric in and out of them, all under the stern eye of Chanel, played by soloist Yang Ruiqi.

This was only the second rehearsal, and Lopez Ochoa “is in awe” that the dancers were able to remember everything, after having put the scene together in a single session – “I create very fast,” she says.

Now she is working on the details, making the dancers repeat moves over and over until she is satisfied. Things are brisk and businesslike, but there’s plenty of laughter, too. When I mention this, she says that while she is very demanding, “humour is my weapon and it’s also who I am. And I’m most creative when I can play.”

Where else, she asks, can you “come into a studio and create a new reality. Isn’t that magical? That you work for three hours and suddenly there’s a whole scene, a whole world?”

Neither the choreography nor the score – by Lopez Ochoa’s frequent collaborator, award-winning British composer Peter Salem – will draw on period material, although the music, performed by the Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra will have a French feel, and Lopez Ochoa will go from a “waltzy” movement early on to a much freer style by the second half.

The costumes, by another frequent collaborator, Jérôme Kaplan, are inspired by Chanel’s designs, but won’t reference them specifically. “High fashion is all about details, something you see close up,” says Kaplan. “Stage costumes are meant to be seen from a distance. And they need to be danceable.”

When Lopez Ochoa and Kaplan visited a major exhibition of Chanel’s work in Paris, they were both stunned by how timeless the designs are. “That was 1921 and I would buy those dresses now,” says Lopez Ochoa.

For Kaplan, a French designer himself, the opportunity to work on a ballet about Chanel was irresistible.

“She is so important for anyone who is interested in fashion and design,” he says. “And she lived such an extraordinary life.” There is also a personal connection: “My mother’s family was from the area where Chanel was born – from our home you can see the mountains of the Cévennes, where she spent her childhood.

“You can still see the kind of house her family lived in – this was real poverty, no electricity, no running water, bitterly cold winters. People now don’t understand what it was like.”

On a mission to free herself from that early deprivation, Chanel was one of the first designers to emancipate women from the corseted, cumbersome clothes and elaborate hats that were the norm when she started out.

Kaplan notes that her first shops became successful during World War I, “when many women were working because the men were away fighting. So Chanel’s designs, which were practical, gave more freedom of movement and didn’t require a maid to help you dress and undress, matched the need of the time.” Yet despite their simplicity, “her clothes were elegant and allowed women to be elegant in all circumstances”.

Lopez Ochoa agrees: “She’s all about elegance. And classical ballet lends itself to what is the perfect line. I want to create the ballet as she would create it. I love her quote saying, ‘Before you go out of your apartment, you should look in the mirror and take one thing off’.”

The famous double-C logo, which Lopez Ochoa sees as embodying “simplicity and serenity” is a case in point. Nobody knows for sure where the double C idea came from, but the choreographer has gone with the theory that it refers to Capel and Chanel and “represents eternity, that he will stay forever in her heart, so then it becomes a circle and that’s infinity”.

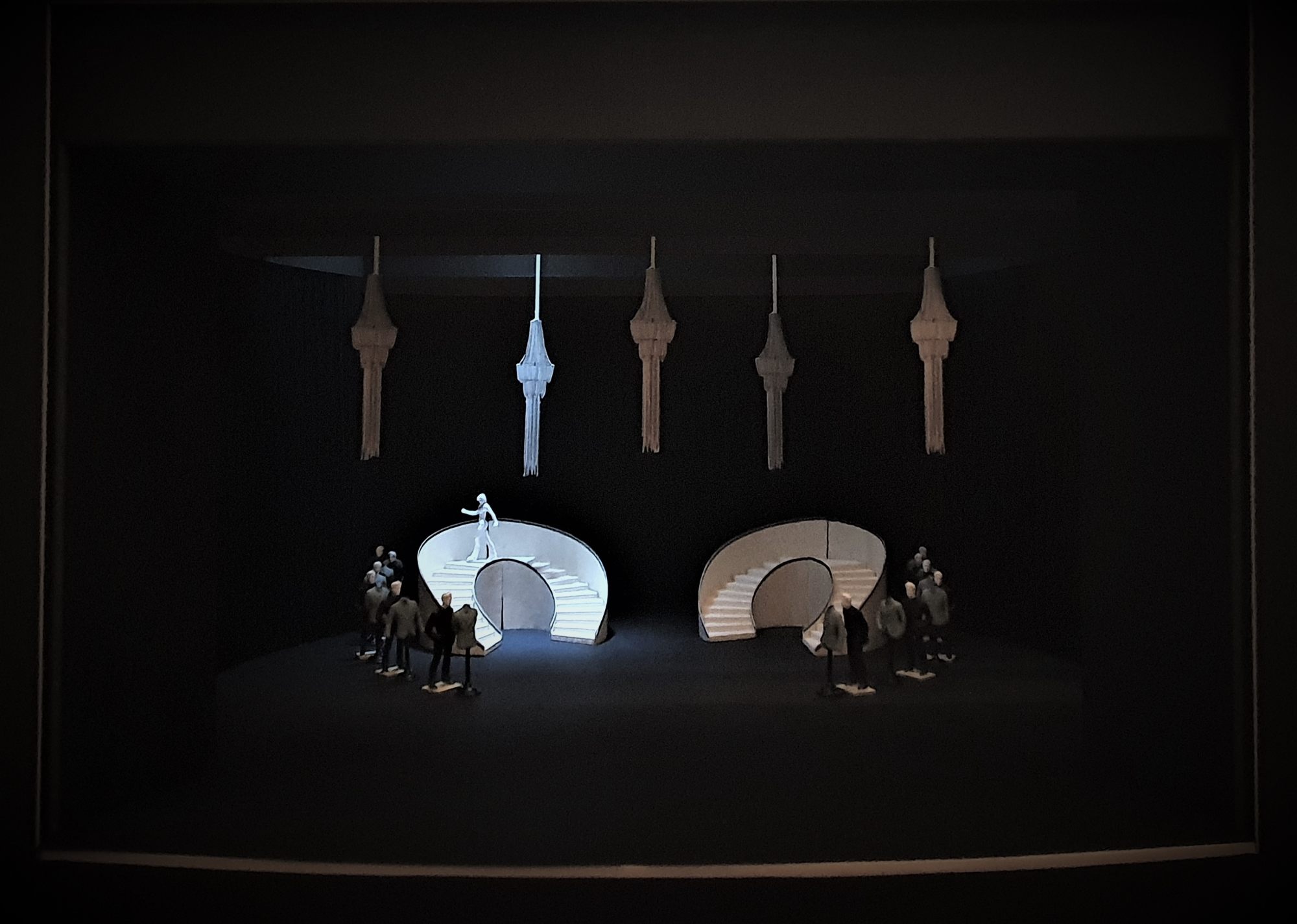

As well as the costumes, Kaplan is also designing the sets, which will echo both Chanel’s focus on simplicity, and characteristic monochrome colour schemes. Key features of the sets are two staircases, which can be moved around to create various spaces on the stage.

They are symbolic of Chanel’s life, climbing upwards from poverty to wealth and success, notes Kaplan, and also recall an image widely associated with her – the legendary mirrored staircase in her Paris home at 31 Rue Cambon.

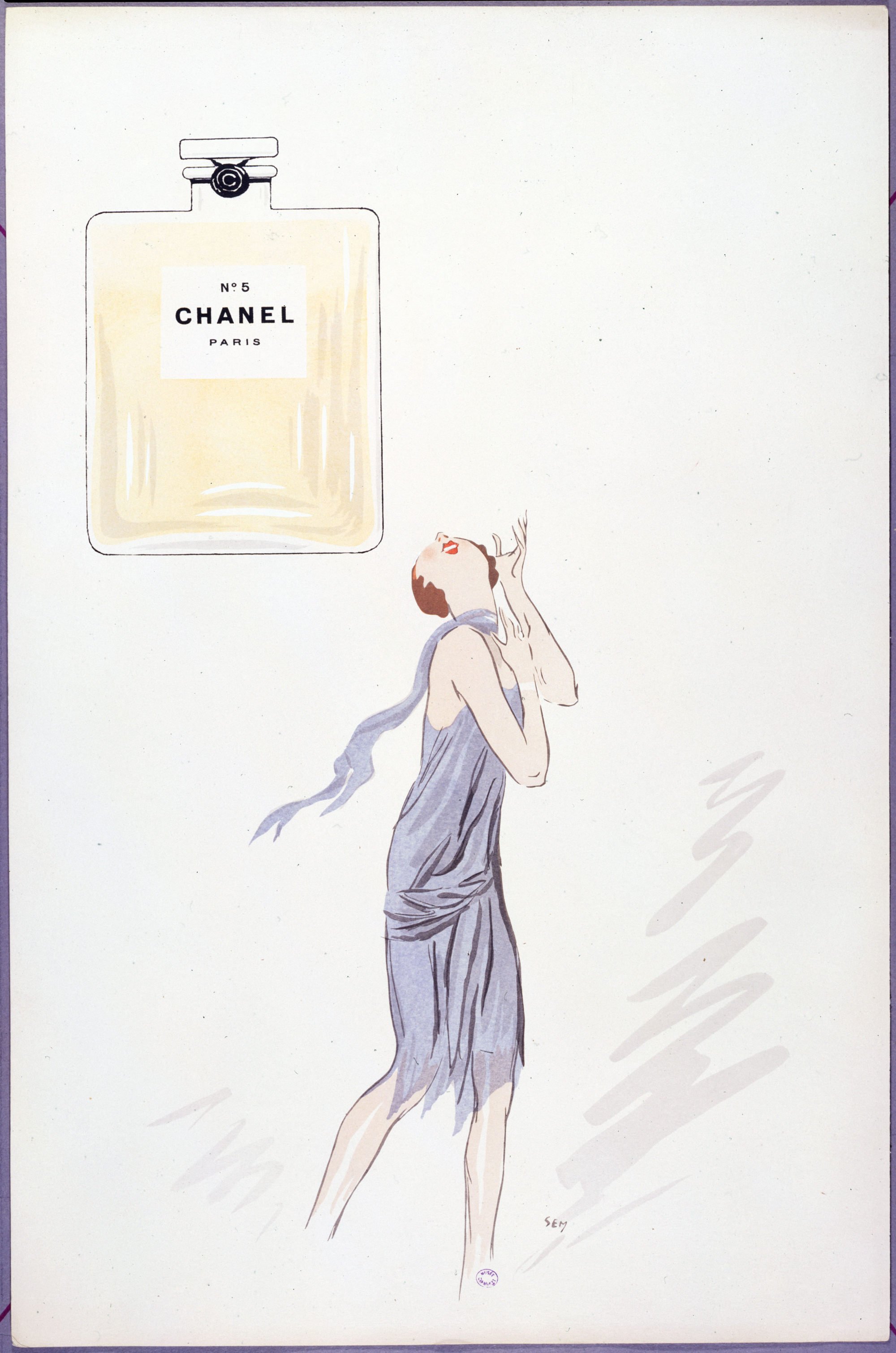

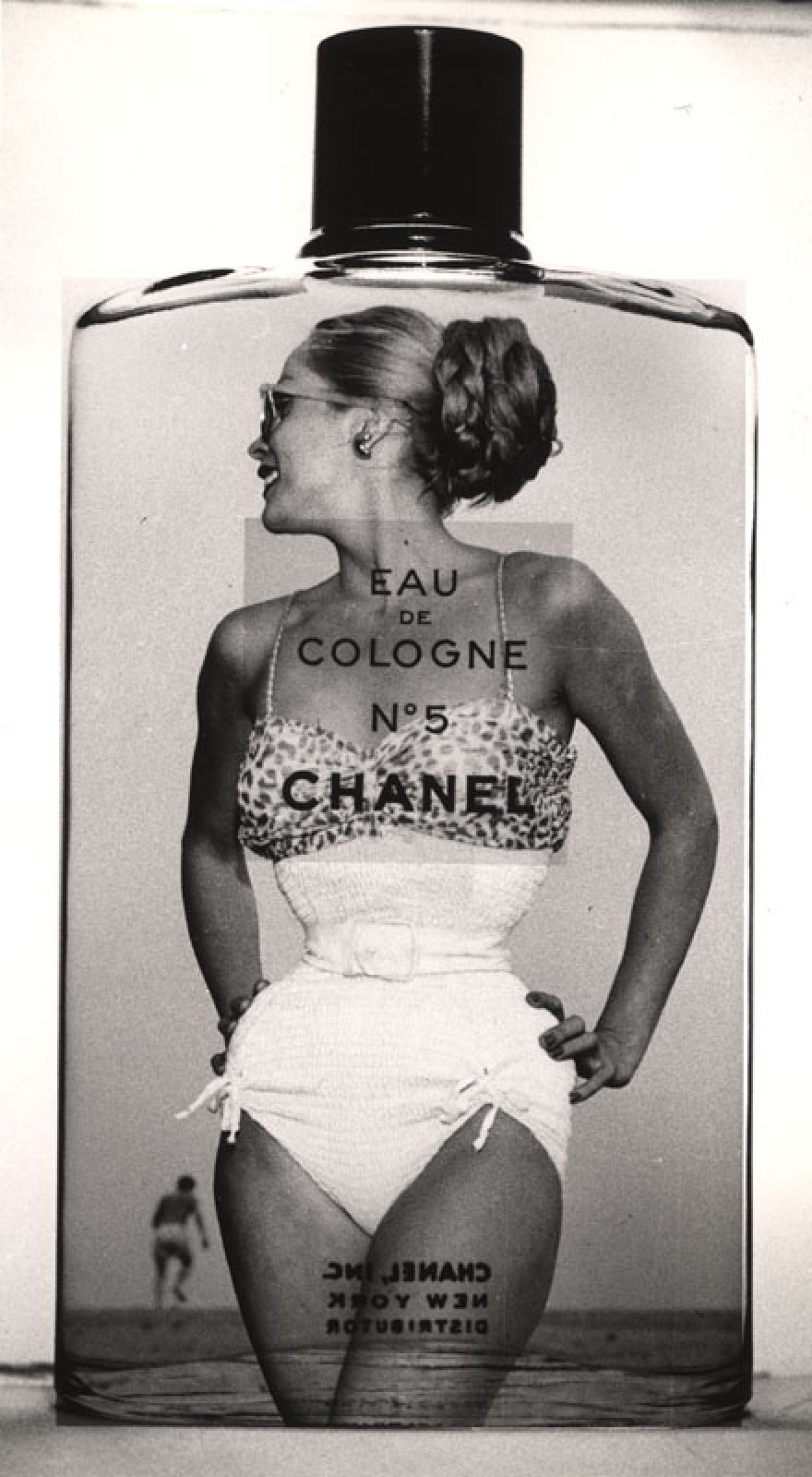

The concept for the sets comes from the iconic design of the Chanel No 5 box – essentially unchanged since its creation more than 100 years ago.

Act 1 will be all ivory white, while Act 2 will be black, as we move into a darker time for Chanel and the world at large, and, says Lopez Ochoa, “because we all have a hidden side, a side we’re not so proud of”.

In 1924, Chanel had made a business deal setting up a company called Parfums Chanel to produce and distribute Chanel No 5 with Théophile Bader, founder of Galeries Lafayette, and Pierre Wertheimer, owner of the Bourjois perfume empire, both Jewish.

Chanel came to believe the deal (which gave her 10 per cent of the stock) was unjust, and that Wertheimer had cheated her.

She became obsessed with getting control of Parfums Chanel and, in 1941, seized the opportunity of new laws stripping Jews of their assets to petition the occupying German authorities for ownership of the company.

If you don’t love your main character, you don’t understand them, you can’t put yourself in their skin, then you can’t tell their story.Annabelle Lopez Ochoa, choreographer of Coco Chanel: the Life of a Fashion Icon

It did nothing to help her image either that once war had broken out, in 1939, Chanel closed her couture business (throwing her 4,000 employees out of work – perhaps in retaliation for their having taken part in the French general strike of 1936) and, in 1940, moved into an apartment at the Hotel Ritz, the favoured residence of the German high command during the occupation.

There she began an affair with senior German intelligence operative Baron Hans Günther von Dincklage – a relationship that continued beyond the Nazis’ defeat, well into the 1950s.

In Act 2 of the ballet, Chanel will be seen denouncing Wertheimer to the Nazis. However, Lopez Ochoa believes what motivated her actions was that, “in a man’s world, she signed a contract as a young designer and they had 90 per cent of the income from her perfume and she had 10 per cent.

“She was always very bitter about that and tried to get her independence back and therefore denounced [Wertheimer] because he was Jewish.”

In fact, Chanel was 41 years old and had been running a business for more than a decade when the Parfums Chanel contract was signed. And was a deal that gave her 10 per cent of the company without having to do any work or bear any costs really so unfair?

It is certainly the case that Chanel moved in circles where antisemitism was rife. Her lover, the Duke of Westminster, held pro-Nazi views; another long-term lover was illustrator and designer Paul Iribe, whose publication Le Témoin (which Chanel supported financially) was a platform for ultranationalist and xenophobic politics.

In any case, Wertheimer had the last laugh, having transferred control of Parfums Chanel to a non-Jewish businessman, Félix Amiot, in 1940, so Chanel’s petition failed – Amiot returned the business to him after the war.

Lopez Ochoa feels that Chanel’s actions were not inspired by a dislike of Jewish people but “what she hated was the fact that she signed a contract and they got the better of her, so she thought ‘Now I can get back at you because the cards have changed’.”

“I can judge her, or I can try to understand the root of that decision and therefore tell her story with empathy but also say that [what she did] wasn’t right.”

The legal wrangles over Parfums Chanel continued after the war. Forbes Magazine commented that Wertheimer had a dilemma, since “a legal fight might illuminate Chanel’s wartime activities and wreck her image – and his business”.

In the end, Chanel agreed to a new deal whereby she would receive 2 per cent of the company’s profits and the Wertheimers would pay all her living expenses for the rest of her life.

Lopez Ochoa points out that both Chanel and the Wertheimers were, essentially, opportunists. In 1954, when Chanel was in exile in Switzerland, the Wertheimers offered to finance her new collection, leading to her ultimately triumphant return to the international fashion scene.

“In the end, they saw her genius and creativity and visionary quality and saw they could make money from it,” says Lopez Ochoa, “so they used each other.”

And they’d all been engaged in such games, of varying degrees of complexity, for a while. Declassified documents show that in 1943, Chanel was involved in a plan with SS General Walter Schellenberg to use her personal connection with Churchill to negotiate a peace treaty between Britain and Germany.

The plot failed, but when Chanel was interrogated by the French authorities in 1944 it appears that Churchill intervened to procure her release – perhaps to prevent her revealing damaging information about the pro-Nazi sympathies of influential members of the British elite.

After Paris was liberated in 1944, Chanel left France for Switzerland, where she remained for nine years. She was never charged with any wartime offences.

If the verdict remains open on Chanel herself, her legacy as a designer is secure. For Lopez Ochoa, in creating a ballet based on such a complex life, “if you don’t love your main character, you don’t understand them, you can’t put yourself in their skin, then you can’t tell their story. Because I think in essence we all mean well, but sometimes to survive we don’t make the right decisions.

“Like the whole anti-Semitic [she pauses to find the right word] ‘episode’ is a woman in a man’s world who will do everything to survive.”

But Chanel’s essence, and legacy, remains in her passion, an aspect of Chanel’s character that Lopez Ochoa “can really see in myself”.

“For me, creating is not work, it’s passion and [Chanel] loved that.”